CHAPTER 2

Molecular Links between Obesity, Hypertension and Metabolic Dysfunction

GEOFFREY A. HEAD,* KYUNGJOON LIM, BENJAMIN BARZEL, SANDRA L. BURKE AND PAMELA J. DAVERN

Neuropharmacology Laboratory, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, 75 Commercial Road, Melbourne 3004, Australia

*Email:

[email protected]2.1 Introduction

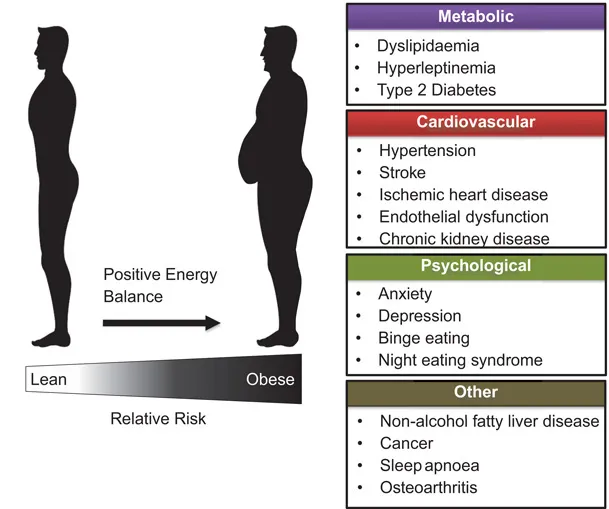

The alarming increase in the prevalence of obesity and the ensuing dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease occurs both in developed and developing countries. The enormity of the health issues of being overweight or obese is therefore a major worldwide burden of disease that promises to outstrip the capacity of health systems to cope.1 This is due to the increased incidence of metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease and premature death (Figure 2.1). It is expected that in countries like the USA and Australia the prevalence of being overweight or obese will increase to 75% for females and 83% for males by 2025.2 At this time and even now, the normal condition of the population will be overweight or obese. The consequences of obesity are a range of metabolic changes that have been incorporated to define a “metabolic syndrome”.3 These include dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, which is the primary feature of type 2 diabetes. The progression from obesity to metabolic dysfunction to hypertension and diabetes ultimately occurs unless there are significant interventions. It is thus very important to understand the short term and long term impact on health and wellbeing of being overweight or obese.

Figure 2.1 Illustration of the deleterious health conditions associated with a long term positive energy balance resulting in the progression from being lean to obese. The consequences include an increased relative risk of metabolic, cardiovascular and psychological disease.

There is also a considerable reduction in the quality of life related to reduced mobility, public stigma, negative psychological changes including depression and higher levels of unemployment. While effective weight loss therapies including dieting, pharmacological appetite suppressing agents and even surgery are currently only partly successful and have some issues, this should not diminish our resolve to find solutions. Clearly evidence-based allocation of resources for prevention, reduction and mitigation should be a major priority. However, it should be understood that the long term impact of obesity-related metabolic disease is cardiovascular disease associated with greater rates of atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart disease, vascular disease and cardiovascular-related mortality. The analysis of the Framingham cohort suggests that over two thirds of newly diagnosed cases of hypertension are related to being overweight or obese.4 While there are many factors contributing to the increase in blood pressure in obese and overweight patients, increasingly there is recognition of the important contribution of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS).5–10 The major regulatory site relevant to obesity lies in the hypothalamus which is known for its role in regulating fluid balance, blood volume and sodium homeostasis but is also an important center for the integration of neural and hormonal signaling. In obesity, the most relevant of the peripheral signaling molecules are the adipokines leptin and adiponectin, the hormone insulin and gut hormones such as ghrelin. These hormones signal metabolic information to the central nervous system (CNS) via designated receptors within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. We know a great deal about the afferent and efferent neural connections of the hypothalamus, as well as the nature of the neurons within its subnuclei that influence hormonal signaling molecules. The hypothalamus is also an important region for the integration of the neural response to acute emotional stress. There may well be overlap between the hypothalamic pathways processing the autonomic responses to stress with those responding to metabolic signals. Thus, to unravel the molecular links between obesity, hypertension and the metabolic cause of CNS dysfunction in obesity is clearly a major health priority. The purpose of this review is to document the progress in our understanding of the processes involved in the development of obesity-related hypertension, metabolic and cardiovascular disease that has been made in recent years and perhaps to indicate the path for future research.

2.2 Consequences of Obesity on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease

There is now convincing evidence for a causative association between obesity and metabolic disease, including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and the development of type 2 diabetes, although the mechanisms are not fully understood. The dyslipidemia accompanying obesity includes higher levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles,11 reduced levels of high density lipoproteins (HDL) as well as elevated plasma triglycerides.12 All of these trends are atherogenic.12 There is a two-fold increase in the risk of having high triglycerides, reduced HDL and other aspects of metabolic syndrome if you are obese and a four-fold increase in the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.13 The AusDiab population study shows us that the incidence of impaired fasting glucose or glucose tolerance in Australia in 2005 was 14%.14 Future adult levels of diabetes (from 2010 to 2030) will increase by nearly 70% in developing countries from a somewhat lower base and by 20% in developed countries.15 The complications associated with obesity and in particular if type 2 diabetes develops, include coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease and endothelial dysfunction. While the metabolic syndrome comprises a number of conditions, obesity is independently associated with endothelial dysfunction.16 Mechanisms may involve elevation in specific adipokines, reduction in adiponectin as well as cytokine-induced oxidative stress and low level inflammation. Vascular indicators of inflammation like fibrinogen, plasminogen activation inhibitor and C-reactive protein are also positively correlated with obesity.17 Dyslipidemia is also associated with pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis and atherosclerotic arterial disease.17 Of particular concern is the much higher rate of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome in indigenous Australians where a recent study shows that almost one third of those aged over 35 and over half of those over 55 years have type 2 diabetes.18

A major cardiovascular consequence of obesity is the risk of myocardial infarction, particularly in men. While a third of cases of elevated triglyceride and reduced HDL are due to obesity in women, this is associated with only 13% elevated risk of myocardial infarction. However, for men less than 20% of cases of dyslipidemia are due to obesity but the risk of myocardial infarction is over 30%.13 Perhaps the most important consequence of being overweight is hypertension with over 60% of newly diagnosed cases of hypertension being related to obesity.4 While most patients are unaware of their hypertension, the first indication can often be a stroke, myocardial infarction or renal failure. The Renfrew–Paisley study which followed over 15 000 subjects for two decades found subjects with a BMI greater than 30 had a 1.5–2.5 fold greater risk of coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, venous thromboembolism and atrial fibrillation compared with normal subjects with a BMI less than 25.19 Both systolic and diastolic dysfunction can occur due to the concentric cardiac hypertrophy from elevated blood pressure which is compounded by advanced coronary artery disease.17 The greater body mass due to both excess fat and also greater lean body mass results in increased oxygen demand, greater blood volume, cardiac output, stroke volume and eccentric cardiac hypertrophy.20 Prolonged obesity and hypertension may also cause glomerular hypertension, hyper-filtration and loss of renal function as well as increased salt sensitivity.21

2.3 Role of the SNS in Obesity-related Hypertension

The mechanism of hypertension has been extensively studied particularly in animal models where central actions of leptin in the hypothalamus result in increased sympathetic activity to peripheral blood vessels, predominantly to the kidney, causing elevated blood pressure.22,23 Initial breakthrough discoveries from Landsberg and colleagues recognized the robust effect of eating on the activity of the SNS.24 Bray was the first to propose a model that implied that the effects of obesity included a reduction in activity of the SNS but this study focused on determining the metabolic effects of the SNS on the liver, brown adipose tissue, pancreas and adrenal glands.25 Since then, it has become apparent that there are variations in SNS activity dependent upon inputs to differing regional beds t...