1.1 CHEMISTRY IN THE ATMOSPHERE

Our atmosphere is an extraordinary mixture of gases and suspended particles, some inert and some highly reactive, some present in large quantities while others are found only in the minutest traces. New material is being added continuously to the atmosphere at the surface boundary, with materials trapped within the Earth, perhaps when the planet was formed, being liberated, sometimes slowly and gently, and sometimes violently in volcanic eruptions. So far, this description would also fit the atmospheres of our near neighbours Venus and Mars. But on Earth, the living organisms (the biota) make a quite dramatic contribution of their own to the supply of chemicals to the atmosphere. Humans are part of the biota, and are making an impact on the atmosphere out of all proportion to human life’s biological importance, as we shall see time and again in this book. The study of the chemistry of the ‘natural’ atmosphere is truly fascinating in its own right. But it is also clear that the chemist who has a good understanding of how this natural atmosphere works is one of the most likely candidates to make rational and informed suggestions about ways to offset Man’s depredations. Policy makers (and politicians) need chemists!

The mixture of gases and particles naturally contains many substances that can react with others that are present, and one of the primary tasks of the atmospheric chemist is to interpret the composition of atmosphere in terms of the pathways and rates of the reactions that occur. A knowledge, preferably obtained from experimental observations, of the possible mechanisms and of the chemical kinetics of the reactions thus lies at the core of this aspect of atmospheric chemistry. It is often helpful to imagine the atmosphere as a giant chemical reactor in which the chemical soup interacts to remove some components and to replace them with new species.

Of the biogenic gases, the most notable both in abundance and in properties is oxygen, O2, produced by photosynthesis. The existence of life allows oxygen to make up about one-fifth (21 per cent) of Earth’s atmosphere, while oxygen is almost absent from the atmospheres of Venus and Mars. However, many of the other gases released are reduced (CH4, H2S, (CH3)2S, for example), or at least only partially oxidized (CO and NO will serve as examples). Much of the chemical change in the lower part of the atmosphere thus consists of oxidation steps that lead ultimately to CO2, H2O, SO3, NO2 and N2O5 for the examples presented. We will look again at these products quite soon. For the moment, the significant feature to note is that the atmospheric conversion steps are driven, directly or indirectly, by solar ultraviolet radiation, so that the atmosphere is not just a reactor, but a photochemical reactor. To be sure, chemistry continues at night: charged particles from the Sun and lightning discharges provide energy for some reactions, while others can be promoted thermally near volcanoes. But by far the greatest proportion of the chemistry that we have outlined so far is ultimately dependent on photons emitted by the Sun.

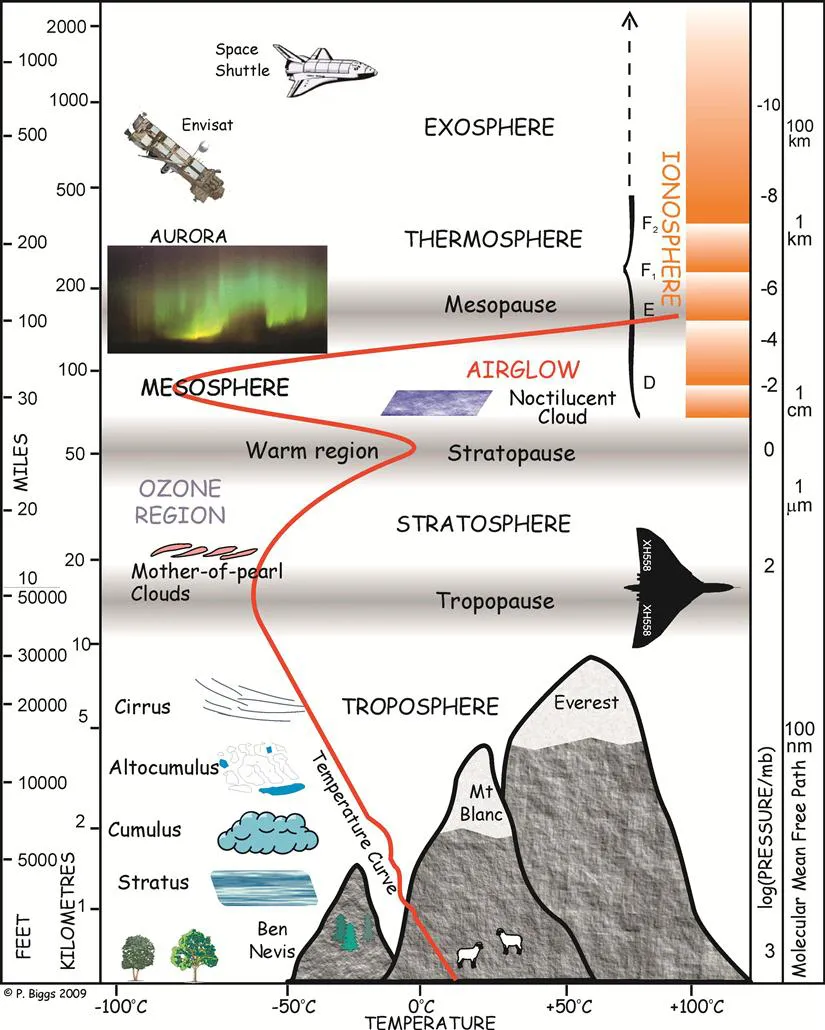

This apparently simple picture of chemistry in the lower part of the atmosphere not surprisingly reveals considerable complexity when looked at more closely. It is at this point that the very close interactions between chemical, physical, biological and geological processes become evident. Chemical change is greatly influenced by temperature and pressure; not only the rates of reactions, but even the pathways open for reaction and thus the products formed may depend on these two factors. As a result, in the atmosphere altitude, latitude and longitude may all play a part in determining which processes occur, or at least compete successfully with alternative pathways. Pressures and temperatures in the atmosphere fairly obviously change with altitude, although the behaviour turns out to be far from obvious. It is here that we encounter the concept of different regions of the atmosphere, such as the troposphere, the stratosphere and the mesosphere, in which the classification is based on temperature structure. Figure 1.1 shows where the regions are located. Altitudes z are shown on the left-hand vertical scales, and temperatures T are plotted horizontally; the line shows how T varies with z. Atmospheric motions transport substances that live long enough to other heights and places. Reactions take place on the surfaces of suspended solids (aerosols) such as ice, soot and dusts, and within droplets (liquid H2O clouds, for example), as well as just within the gas phase, so that physics and meteorology are necessarily again involved in a detailed description of atmospheric chemistry. But chemical composition, and chemistry itself, may have an effect on temperatures, so there is a reverse interaction. Biology makes many of the chemicals released to the atmosphere, but life is sustained or shielded in one way or another by the atmosphere. Geology and geochemistry influence the chemical composition of the atmosphere, and in turn are influenced by it. It is worth noting, too, how the interactions often run in two directions: temperature affects chemistry, but chemistry influences temperatures. These so-called feedbacks thus need to be taken into account when attempting to understand atmospheric behaviour. Indeed, we do not get to a very deep understanding without considering the feedbacks between all the systems taken as a whole. It’s a complex and daunting task, but a fascinating and scientifically stimulating one that provides insights at all sorts of levels.

Figure 1.1 The temperature structure of the atmosphere. Temperatures show a complex dependence on altitude, decreasing with altitude at some heights but increasing at others. The turning points of the temperature gradient mark the boundaries between regions of the atmosphere. The diagram indicates the clouds and other features found at different altitudes. The right-hand ordinate scale shows both the pressure and the mean free path (λ) corresponding to the left-hand altitude scales. This version of the figure was constructed in 2009 by Dr P. Biggs, who kindly gave permission for its use here.

1.2 EARTH’S ATMOSPHERE IN PERSPECTIVE

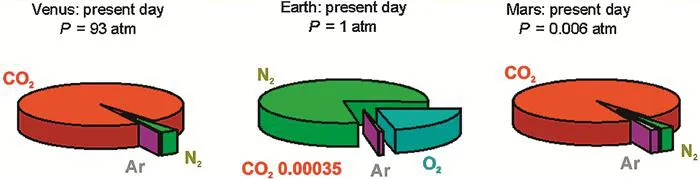

Although we shall consider many more of the effects that life has had on Earth’s atmosphere later in the book, it is interesting to examine the pie charts in Figure 1.2, which indicate the actual compositions of the atmospheres of Venus, Earth and Mars. Comparison of the chart for Earth with the charts for Venus and Mars, the planets on either side of us, will show just how dramatically the existence of life on Earth has altered the composition of our atmosphere, particularly with respect to the proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Figure 1.2 Abundances of gases in the atmospheres of Venus, Earth and Mars. The pie charts show the fractional abundances of the dominant gases, while those of other key components are shown in parentheses. Data for contemporary atmospheres are taken from R.P. Wayne, Chemistry of Atmospheres, 3rd edn, OUP, 2000, who cites the original references.

At this point, the unexpected nature of the Earth’s atmosphere becomes apparent. Since Earth lies in the solar system between Venus and Mars, Earth’s atmosphere might have been expected to consist primarily of the oxidized compound, carbon dioxide. But CO2 is only a minor (although very important) constituent. The presence of elemental oxygen as a major constituent is obviously one of the most significant features of our atmosphere and has some of the greatest impacts on its chemistry. Earth’s atmosphere appears to be a combustible mixture, since there is too much oxygen in the presence of too many gases that react with oxygen. Oxygen reacts with hydrogen to form water, with nitrogen to form nitrates, with methane to form carbon dioxide and water, and so on. Biological processes are dominant in the production of the oxidizable components of our atmosphere, and Earth’s atmosphere consequently maintains a steady-state disequilibrium composition. Furthermore, the entropy of the atmosphere is effectively reduced—the energy required for this reduction is supplied almost entirely by radiation from the Sun, which enables biology to produce both oxidizable components and, of course, oxygen.

As any high-altitude mountaineer will attest, most of this oxygen is found close to the surface of the Earth, and the atmosphere loses density very quickly as an ascent is made. Gaseous components in the atmosphere do not settle down on the planetary surface under the influence of gravitational attraction because the translational kinetic energy of the atoms or molecules competes with the forces of sedimentation. As a result of this competition, the density of gas falls with increasing altitude in the atmosphere. For the bulk liquids and solids of the oceans and land, the masses of the individual ‘particles’ are so great that this competition is completely ineffective, although if the material is finely divided enough it can remain in atmospheric suspension (an aerosol: see Section 1.3).

The total mass of Earth’s atmosphere is around 5×1018 kg. Half of this mass lies below an altitude of about 5.5 km and 99 per cent of that mass can be found below roughly 30 km, although several atmospheric species may still be found some 160 km or so above sea level, and ions of atomic and molecular hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen can be found many hundreds of kilometres from the surface of the Earth. However, where the outer ‘boundary’ of the atmosphere actually occurs is extremely difficult to define; at an altitude of 100 km the pressure is only about one millionth of that at sea-level and the average distance between collisions of the atoms and molecules (the mean free path, λ), has reached 1 mm, several million times greater than the diameters of the colliding partners. At this altitude, chemical reactions are already rather slow because the reactants have such a low chance of colliding with each other. By the time we reach 160 km above the surface, the probability of collisions is very low indeed, and the mean free path is around 100 m.

Our high-altitude mountaineer will have also discovered that, like the density, the temperature decreases as we climb higher. In fact, it drops by about 6 K for every additional kilometre of altitude even for ...