![]()

CHAPTER 1

Concept of Structure–Property Relationships in Molecular Solids and Polymers

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Low molar mass organic molecules and polymeric materials are often found as solids and their physical properties are a consequence of the way in which they are organized: their morphology. The morphology is a result of specific molecular interactions which control the way in which individual molecules pack together to form a solid. Depending on the strength and nature of the interaction, a short- or long-range structure may be created and this leads to the formation of a crystalline, liquid crystalline, gel or amorphous solid. As we shall see later, the organization created at a molecular level may influence the longer range structures, but in other cases it does not, hence the subtitle of the book: From Nano to Macro Organization in Small Molecules and Polymers.

Synthetic polymers, often referred to as plastics, are familiar in the house as furniture, form the frames for double glazed windows, shopping bags, furnishings, carpets, curtains and covering for chairs, cabinets for televisions, paper and paint on the walls. Outside the house, plastics are used for septic, water and fuel storage tanks, garden furniture, water hoses, traffic cones, and they play an important part in automobiles, aircraft and sundry other items which we see around us. Removal of all articles containing polymers from a room would leave it bare and would require removal of human beings themselves, as we are all made up of polymeric materials. Synthetic plastics form the basis for many forms of food packaging, containers for cosmetics, soft drink containers and the trays used in microwave cooking of food. Natural polymers such as wood, cotton and wool all exhibit a high degree of order. Biopolymers, which are the very substance of life—as a consequence of specific, usually hydrogen bonding interactions—create morphology which forms the scaffold for life. Many inorganic oxides, silicates, phosphorous, boron nitride, sulphur etc. possess polymeric structure which imparts specific physical properties to the solids and have an identifiable nano structure.

Whilst the focus of this monograph is structure in polymeric materials, many of the interactions which control the organization of big molecules are best studied with lower molecular weight analogues. It is therefore appropriate to spend some time understanding small molecular systems before considering the complexity of macromolecular systems. It would be an impossible task to produce a compendium of structures for all known materials, this text rather attempts to illustrate some of the better known systems and hopefully will aid newcomers to this area of science to develop an understanding of the way we can control interactions at a molecular level and create ordered or disordered large-scale materials.

The bulk physical properties of a material are dictated by a complex balance of short and longer range interactions. If a molecule possesses specific interactions it may self assemble and form a crystalline or liquid crystalline form on cooling. However, rapid cooling will often allow the disordered characteristic of the liquid to be retained in the solid and create a less ordered or even an amorphous structure. Polymer chemists have for many years sought to establish structure–property relationships that predict various physical properties from a knowledge of the chemical structure of the polymer. Staudinger1, 2 recognized that polymers or macromolecules were constructed by the covalent linking of simple molecular repeat units. This is implied in the term poly, meaning many and mer, designating the nature of the repeat unit.3, 4 Thus poly (ethylene) is the linkage of many ethylene units.

nH2C=C2H→−(CH2−CH2)−n

Recognition of the nature of this process of polymerization made it possible to produce materials with interesting and useful properties, and led to the creation of polymer science. The value of ‘n’ indicates the number of monomer units in the individual polymer chain.

In the last fifty years, a very significant effort has been directed towards understanding the relation between the chemical structure of the polymer repeat unit and its physical properties.5, 6 In the ideal situation, knowing the nature of the repeat unit it should be possible to determine all the physical properties of the bulk solid. Whilst such correlations exist, they also require an understanding of the way in which the chemical structure will influence the chain–chain packing in forming the solid. Similar correlations can be created for the understanding of other forms of order in lower molecular weight materials.

1.2 CONSTRUCTION OF A PHYSICAL BASIS FOR STRUCTURE–PROPERTY RELATIONSHIPS

Why do structure–property correlations apparently work?

1.2.1 Ionic Solids

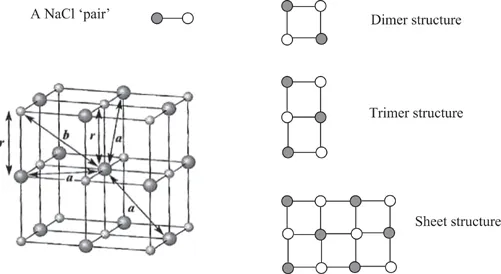

In order to understand the basis on which structure–property correlations operate, it is appropriate to consider the structure of simple ionic solids. A solid sodium chloride single crystal, Figure 1.1, can be constructed, starting from the atomic species of sodium [Na+] and chlorine [Cl−]7. Since each ion carries a single charge, pairing the atoms to form a NaCl pair would create a lower energy state than that associated with the separate ions. This pair will have a minimum separation and would be charge neutral. The line formed between the two atoms can be considered to lie on the x-axis. If another pair of atoms were brought close to the first pair, then once more a minimum energy situation would be created if the two pairs of atoms were aligned but their orientations were in the opposite sense. This arrangement will have a lower energy than the isolated pair and the distance between the atoms will be slightly reduced compared with that of the isolated pair. A further reduction in energy will occur by bringing to the cluster of a further pair of atoms. This latter pair will align in an opposite sense to the pair to which it attaches itself. Once more there will be a small change of separations to reflect the formation of a lower energy state. It is relatively easy to see that this process can be repeated and a sheet of atoms would be formed. As we will see later this is principle is used in consideration of attachment and growth of molecular and polymeric crystals.

Figure 1.1 NaCl type of crystal structure.

The sheet of atoms formed by the process described above is not the lowest energy structure that can be formed. If this original sheet is sandwiched between to similar states such that each of the Na and Cl atoms becomes surrounded by atoms of the opposite sign then a true minimum energy will be observed. If this ordered structure cannot be formed, because the entropy (disorder) is high, then the ensemble of atoms will be in the melt or, at very high temperatures, the gaseous state. Rapidly cooling a melt can also trap in disorder in the solid which is formed and, depending on the strength of the individual interactions, an amorphous or a partially crystalline form may be created. Quenched solids may be trapped in an artificial ‘high energy’ state and can slowly change into the lower energy, thermodynamically more stable crystalline state. The structure observed contains a history of the process used to form the solid.

In the case of the NaCl crystal, this lowest energy structure is cubic closed packed and results from each atom having six neighbouring atoms of the opposite sign. Changes in the size of the ions and their charges lead to different type of packing being favoured. However, it is relatively easy to see that an average energy can be ascribed to a basic unit of the structure and this will reflect the physical properties of the bulk. Whilst the energy of the first pair can be calculated explicitly, adding additional elements means that the force field has to be averaged and will give rise to the problem of how you calculate the interaction of many bodies all interacting. The energy is the result of electrostatic–Coulombic interactions between unit charges and in principle can be relatively easily calculated by averaging all the interactions that will act on an atom chosen as the reference. The above example illustrates not only the lowering of the energy by surrounding an atom by other atoms but it illustrates that atoms in the surface will have a higher energy and we will meet this concept again when we consider polymer organization at interfaces. In the case of cations, changing their oxidation state will also influence the way in which the anions will form the cluster and this will influence the symmetry of the crystals which are formed.

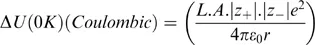

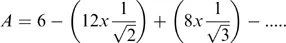

The total number and relative magnitudes of the Coulombic interactions and whether they are attractive or repulsive are taken into account by using a factor known as the Madelung constant, A. The lowest energy for the lattice ΔU(0K) (Coulombic), referenced to absolute zero, can for an ionic lattice be expressed by:-

where ∣z+∣ and ∣z−∣are respectively the modulus of the positive and negative charges, e is the charge on the electron {=1.602 × 10−19 C}, ε0 is the permittivity of a vacuum=8.854×10−12 F m−1 r is the intermolecular distance between the ions (units=m), L is Avogadro’s number (6.022×10−23 mol−1) and A is the Madelung constant.

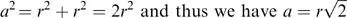

The Madelung constant takes into account the different Coulombic forces, both attractive and repulsive that act on a particular ion in a lattice. In the Na Cl lattice, six Cl− atoms surround each Na+ atom. The coordination number, 6, describes the number of atoms which surround the selected reference atom. X-ray analysis indicates that each atom is a distance of 281 pm (=2.81Å) from its nearest neighbour. To calculate the Madelung constant we consider the four unit cells that surround the selected reference atom. Firstly, there are twelve Cl− ions each at a distance a from the central ion, and the Cl− ions repel one another. The distance a is related to r by the equation:

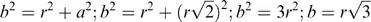

Next, there are eight Na+ ions each at a distance b from the central Cl− ion, giving rise to attractive forces. Distance b is related to r by the equation:

Further attractive and repulsive interactions occur, but as the distance involved increases, the Coulombic interactions decrease.

The Madelung constant, A, contains terms for all the attractive and repulsive interactions experienced by a given ion and so for the NaCl lattice, the Madelung constant is given by:

where the series will continue with additional terms for interactions at greater ...