![]()

1

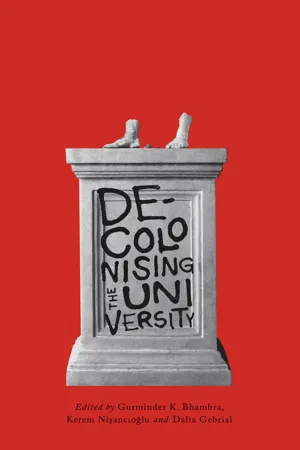

Introduction:

Decolonising the University?

Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu

The call to decolonise universities across the global North has gained particular traction in recent years, from Rhodes Must Fall Oxford’s (RMFO) campaign for a public reckoning with its colonial legacies, to recent attempts by Georgetown University, Washington DC, to atone for its past ties with slavery.1 The UK’s National Union of Students (NUS) has been running ‘Why is My Curriculum White?’ and #LiberateMyDegree as two of their flagship campaigns since 2015. Both campaigns seek to challenge ‘Eurocentric domination and lack of diversity’ in curricula across UK universities.2 These dissenting interventions take their inspiration from and build on similar campaigns in other parts of the world – for example, the Rhodes Must Fall movement in South Africa and the campaigns against caste prejudice occurring in some Indian universities. They also build on earlier movements and protests organised under notions of social justice and addressing inequality. These include campaigns such as those led by the Black and Asian Studies Association concerning the representation of Black history within the UK National Curriculum and those in defence of the ‘public university’ organised by the Campaign for the Public University and Remaking the University, among others.3 These movements, collectively, sought to transform the terms upon which the university (and education more broadly) exists, the purpose of the knowledge it imparts and produces, and its pedagogical operations. This collection aims to critically examine the recent calls to ‘decolonise the university’ within this wider context, giving a platform to otherwise silenced ‘decolonial’ work and offering a resource for students and academics looking to challenge and undo forms of coloniality in their classrooms, curricula and campuses.

I

Given the prominence of decolonisation as a framework in student- and teacher-led movements today, it is incumbent upon us to think more carefully about what this means – as both a theory, and a praxis. How is it distinct from other forms of anti-racist organising in institutions such as the university, and why has it gained particular purchase in the contemporary higher education context? What does it mean to apply a term that emerged from a specific historical, political and geographic context, to today’s world? And what are the possibilities and dangers that come with calls to decolonise the university?

‘Decolonising’ involves a multitude of definitions, interpretations, aims and strategies. To broadly situate its political and methodological coordinates, ‘decolonising’ has two key referents. First, it is a way of thinking about the world which takes colonialism, empire and racism as its empirical and discursive objects of study; it re-situates these phenomena as key shaping forces of the contemporary world, in a context where their role has been systematically effaced from view.4 Second, it purports to offer alternative ways of thinking about the world and alternative forms of political praxis.5 And yet, within these broad contours, ‘decolonising’ remains a contested term, consisting of a heterogeneity of viewpoints, approaches, political projects and normative concerns. This multiplicity of perspectives should not be surprising given the various historical and political sites of decolonisation that span both the globe and 500 years of history.

There are also important methodological and epistemological reasons to emphasise contestation over definitions of ‘decolonising’. Indeed, one of the key challenges that decolonising approaches have presented to Eurocentric forms of knowledge is an insistence on positionality and plurality and, perhaps more importantly, the impact that taking ‘difference’ seriously would make to standard understandings.6 The emphasis on reflexivity reminds us that representations and knowledge of the world we live in are situated historically and geographically. The point is not simply to deconstruct such understandings, but to transform them. As such, some decolonising approaches seek a plurality of perspectives, worldviews, ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies in which scholarly enquiry and political praxis might take place.7 And yet there also remain approaches situated squarely within the anti-colonial tradition that seek to eschew the particularity of Eurocentrism through the construction of a new universality.8 The contested and multiple character of ‘decolonising’ is reflected in the contributions to this volume.

This volume is written from the position and experience of academics and students working in universities primarily in the global North (although many contributors would perhaps insist they are ‘of’ neither). It seeks to question the epistemological authority assigned uniquely to the Western university as the privileged site of knowledge production and to contribute to the broader project of decolonising through a discussion of strategies and interventions emanating from within the imperial metropoles. In this way, we hope it complements the work of scholars and activists elsewhere who have similarly engaged with such issues from across the global South and North.9 In doing so, we hope, collectively, to contribute to practices which provincialise forms of European knowledge production from the centre.10

For example, there are rich and increasingly visible histories of how anti-racist and anti-colonial resistance in the imperial metropole were central to building connections across anti-colonial movements in the global South.11 At the same time, numerous national liberation struggles in the colonies refracted back into struggles around racism and citizenship conducted in the imperial centre.12 In some instances, anti-racist and anti-colonial struggles were articulated in, through, and against Western universities. Campus mobilisations, the formation of student societies, and the publication of student papers knitted higher education and anti-colonialism into a rich tapestry of radical activism in the colonial metropole.13 Taken together, such histories of anti-racist struggle have always included concerns for research and education, in the form of alternative community schooling projects, political education in organisations or campaigns to reform existing educational institutions and policies.14

In short, the turn to decolonising as rubric for political organising in the global North is not rooted in a particular identity; rather, it emerges from shared historical trajectories of forms of colonialism. We hope that a discussion of decolonising from the imperial centre – of which this volume is only one part – might help to reveal something about the machinations of empire in general and the deeply understudied relationship between coloniality and pedagogy. In doing so, it also has the potential to open spaces for dialogue, alliances and solidarity with colonised and formerly colonised peoples, contributing to the making of ‘a global infrastructure of anti-colonial connectivity’.15

II

Why decolonise the university specifically? Should decolonising projects even be concerned with the university as an institution? In an important article, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang remind us that ‘decolonization is not a metaphor’.16 They argue that the language of decolonising has been adopted in ways which empty it of its specific political aims; namely the repatriation of dispossessed indigenous land. Such emptying might include educational practices that seek to move away from Eurocentric frames of reference or using the language of decolonisation while pursuing a politics distinct from indigenous struggles over land. They argue:

The easy absorption, adoption, and transposing of decolonization is yet another form of settler appropriation. When we write about decolonization, we are not offering it as a metaphor; it is not an approximation of other experiences of oppression. Decolonization is not a swappable term for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools. Decolonization doesn’t have a synonym.17

Such acts, Tuck and Yang argue, generate various settler ‘moves to innocence’, which attempt to contain or reconcile settler guilt and complicity. Using ‘decolonization as a metaphor’ thus ‘recentres whiteness, it resettles theory, it extends innocence to the settler, it entertains a settler future’.18 In contrast, Tuck and Yang insist on decolonisation as a struggle over dispossession, the repatriation of indigenous land and the seizing of imperial wealth. Such a project is less about seeking reconciliation with settler pasts, presents and futures, but about pursuing what is ‘irreconcilable within settler colonial relations and incommensurable between decolonising projects and other social justice projects’.19 These are serious warnings which should give us all pause for reflection, not least because we have observed discourses around ‘decolonising the university’ which fall prey to precisely these problems. This volume is an attempt to go beyond such limitations, but will, necessarily, have its own such limitations. We think there is value in complicating the substantive claim made by Tuck and Yang (that decolonisation is exclusively about the repatriation of land to indigenous peoples) in order to extend and deepen their political warning (that decolonisation is not a metaphor).

We hope that the contributions to this volume demonstrate that colonialism (and hence decolonising) cannot be reduced to a historically specific and geographically particular articulation of the colonial project, namely settler-colonialism in the Americas. Nor can struggles against colonialism exclusively target a particular articulation of that project: the dispossession of land. To do so, would be to set aside colonial relations that did not rest on settler projects (such as, for example, commercial imperialism conducted across the Indian Ocean littoral, the mandate system in West Asia, the European trade in human beings, or financialised neo-colonialism today) or to turn away from discursive projects associated with these practices (such as liberalism and Orientalism). It would not only remove from our view these differentiated moments of a global project of colonialism, but also interactions and connections of these global but differentiated moments with settler-colonialism itself. Put differently, whereas disposse...