- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Piano in America, 1890-1940

About this book

Roell uses company records and the popular press to chronicle the piano industry through changing values, business strategies, economic conditions, and technology. For Roell, as for the industry, music is a byproduct.

Originally published in 1991.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition — UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Piano in America, 1890-1940 by Craig H. Roell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Place of Music in the Victorian Frame of Mind

Show me the home wherein music dwells, and I shall show you a happy, peaceful, and contented home.

—Henry W. Longfellow

We cannot imagine a model New England home without the family Bible on the table and the family piano in the corner.

—Vice President Calvin Coolidge

His only outward evidence of prosperity was the purchase of a piano.

—B. A. Williams, Saturday Evening Post

A young woman who has been seated on her lover’s lap at the piano starts up upon being reminded of her lost innocence by the tune being played, her conscience thus called to higher things. Such is the scene in William Holman Hunt’s famous painting, The Awakened Conscience (1852-54). Hunt captured various ideological themes prevalent in Victorian society, themes immediately recognizable to the conscientious middle class. The painting depicts a moral drama and depends on the viewer’s assumptions about woman’s sexual purity (she is dressed in white), her social grace, and the home as the cornerstone of society. Implicitly the painting suggests the moral and spiritual value of music. The parlor piano was an easily understood symbol for all of these Victorian tenets. To play it demanded toil, sacrifice, and perseverance —fundamental virtues in a preindustrialized economy. Faith in the dignity of labor and the moral worth of a productive vocation sustained all types of handicraft, even after the increased development of mechanized production.

The complex intertwining of these notions—whose goal was the maintenance of moral health—formed an ethos that permeated nineteenth-century life and manners. In part, the significance of these Victorian attitudes lies in their persistence into the present century. The American piano industry, its merchandise the product of skilled labor and requiring practiced use, continued to promote these values long after the environment in which they were formed had been supplanted by a new ethos: the consumer society. Understanding the struggles of piano makers in that emerging culture, however, requires a grasp of the peculiar interaction of the work ethic, domesticity, and the morality of music with the piano industry.

Although the term “Victorian” generally describes British society from about 1830 to 1880, it is equally adaptable to (and often used to depict) American society as well.1 For the United States, the term usually denotes the late nineteenth century, though in many ways it also defines the periods historians call the Age of Jackson and the Progressive Era. In this respect, “Victorian” is less a term of periodization than a collection of interrelated attitudes characteristic of a way of life. Emancipating the term from its restrictive boundaries allows the tracing of its collective ideas through time, and provides a better understanding of the erosion of those beliefs when confronted by a new and stronger value system. Hence it is appropriate to speak of “twentieth-century Victorians,” or a “producer ethic in the consumer culture.”

“Victorian” is an elusive term that usually conjures up images of prudery, hypocrisy, middle-class stuffiness, domesticity, sentimentality, earnestness, industry, and pompous conservatism. The moral severity that lay at the center of the Victorian code was a complex response to the needs of an emerging industrial society. Emphasis on work, duty, and effort was a reaction to the new opportunities industrialism provided. The snobbery of the age resulted from the rise of new classes attempting to break into a presumed hierarchy. Victorian hypocrisy developed because ideal standards of conduct proved impossible to maintain consistently. The earnestness and prudery of this code were a reaction against the drunkenness, uncleanliness, debauchery, and wastefulness the Victorians saw in the “uncivilized” preindustrial world they were leaving behind. The “cult of domesticity,”2 with its elevated concept of the home and woman, was an attempt to establish order in a rapidly changing world. This code of moral severity defined the character of individuals as well as the mores of society. Centered upon the middle class and evangelical religion, this morality diffused both downward and upward in the social structure. It influenced politics, government, philosophy, literature and the arts, architecture, education—virtually every aspect of American life. It distinguished Victorian society from the more easygoing ways of the eighteenth century and from the consumer culture emerging in the twentieth century.

Many historians have focused on the nineteenth-century cult of domesticity, with its elevating yet restrictive conception of woman’s place and duty and its notion of the moral superiority of women. Other scholars have analyzed the moral dimensions and extent of the work ethic, noting the interaction of these two cults in Victorian society. Social historians have identified the importance of the piano in middle-class culture, particularly as a symbol of social respectability and as a means of female accomplishment. Still others have demonstrated the cultural importance of music in American life. Yet no one has pointed to the moral interrelation of the work ethic, the cult of domesticity, and music through the medium of the piano. This is crucial to an understanding of the piano—”the altar to St. Cecilia”—as a foundation of Victorian middle-class life

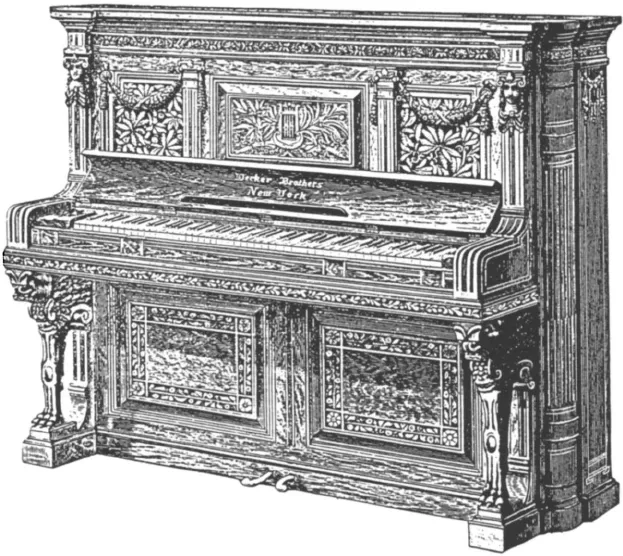

The significance of the piano in Victorian culture rested on a substructure much more intricate than historians have realized. While it is true that the piano was a token of respectability, its importance transcended mere considerations of class or social mobility. The piano became associated with the virtues attributed to music as medicine for the soul. Music supposedly could rescue the distraught from the trials of life. Its moral restorative qualities could counteract the ill effects of money, anxiety, hatred, intrigue, and enterprise. Since this was also seen as the mission of women in Victorian society, music and women were closely associated even into the twentieth century. As the primary musical instrument, the piano not only became symbolic of the virtues attributed to music, but also of home and family life, respectability, and woman’s particular place and duty. Indeed, most piano pupils were female, and both music making and music appreciation were distinctly feminized. The glorification of the piano was no mere fad; it was a moral institution. Oppressive and opulent, the piano sat steadfast, massive, and magnificent in the parlors and drawing rooms of middle-class homes, serving as a daily reminder of a sublime way of life.

Music and Work

The glorification of work as a supreme virtue and the consequent condemnation of idleness remain among the strongest legacies of the Victorian era. Central to this ideology were the notions that nothing in this world was worth having or doing unless it meant pain, difficulty, and effort; that one had a social duty to produce; and that hard work was also morally purifying because it built character, fortitude, self-control, and perseverance. This elevation of work above leisure permeated American life and manners in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, resulting in countless warnings against the evils of idleness. Praise for work came from Protestant middle-class property owners: farmers, merchants, ministers, professionals, craftsmen, and industrialists. And because the middle class controlled the schools, business enterprises, and publishing houses in America, it also set the tone for society.3 The work ethic promised solid rewards, independence, self-advancement, self-respect, contentment, and many other virtues. Throughout the industrial age, respected authorities preached the virtue of work: from Currier and Ives to Horatio Alger, from Ralph Waldo Emerson to Theodore Roosevelt.

In an age glorifying work and worshiping the virtuosos of the work ethic—the Carnegies, Rockefellers, and other captains of industry—American audiences flocked to hear the great piano virtuosos of their day. Not surprisingly, the goal of music teachers was to produce such titans; performance and technique took precedence over all else. In the nineteenth century, the virtuoso achieved heroic stature, often eclipsing the composer. American audiences, perceiving that no native virtuosity yet flourished, eagerly applauded the stream of European artists who just as eagerly toured the New World. The first to arrive was the “Lion Pianist,” Leopold de Meyer, who appeared in about sixty concerts during the 1845-46 season from Boston to New York to St. Louis. In 1850 P. T. Barnum brought the “Swedish Nightingale,” soprano Jenny Lind (with her “angel from heaven” pitch), on a successful tour of America. The pianist Henri Herz achieved similar success from 1845 to 1851, as did Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who returned to his native America in 1853. From 1856 to 1858, American audiences thrilled to the most celebrated virtuoso, “Old Arpeggio” himself, Sigismond Thalberg. It was no coincidence that one industrious entrepreneurial piano maker chose the name “Thalberg” for some of his instruments. America’s love affair with the virtuoso was becoming big business. “It is a pity,” wrote one American reviewer, “but ‘tis true that our people generally would just as soon hear one pianist as another, provided he or she has a name or reputation (honestly acquired, or fictitious, it matters but little).”4

Following the Civil War, professional performances increased, audiences became more sophisticated about music, and promotional techniques became more elaborate. But the virtuoso still reigned supreme. American piano manufacturers, very conscious of the possible financial benefit from endorsement by or association with a great artist, took upon themselves the task of securing and backing concert tours of various musical virtuosos. Beside such efforts, the tours of Herz, de Meyer, Gottschalk, even Thalberg seemed insignificant. Steinway & Sons brought the hypnotic Anton Rubinstein to the United States in 1872, a highly successful promotion that set the pattern for future ventures. Chickering & Sons’ sponsorship in 1875 of Hans von Bülow and in 1879 of the brilliant Rafael Joseffy, while not as financially successful (Joseffy would soon switch to the Steinway piano), further whetted the American appetite for virtuosity. Weber Piano Co. delighted Americans still more by sponsoring the eleven-year-old prodigy Josef Hofmann in 1887, while William Knabe & Co. absorbed the expense of bringing Tchaikovsky to New York in 1891 to open Carnegie Hall as guest conductor.

But it was Steinway & Sons who consistently supplied Americans with laureled musical heroes. In 1891 Steinway invited the famed Ferruccio Busoni on his first American tour. Later that autumn the piano manufacturer brought over Ignacy Paderewski— hypnotic, aggressive, lordly, legendary—who was to be the reigning virtuso for thirty years. The most financially successful of all, the pianist had netted half a million dollars by his third tour in 1896. In an age worshiping the virtuoso, Paderewski was the virtuoso extraordinaire. All over America crowds attended his concerts in record numbers and gathered at railroad crossings to glimpse his profile. And the ever-growing reputation of the House of Steinway was of course simultaneously secured.5

The artists who toured Victorian America would have achieved their well-deserved fame regardless of the cultural mentality of the American people, but the significance of the work ethic in that culture should not be overlooked. Questions of art aside, the virtuoso—whether musical, industrial, or financial—achieved success through “luck and pluck” (in Alger’s timely phrase), but especially through hard work. The phenomenon of the virtuoso was a phenomenon of the Victorian frame of mind. The work ethic and the accompanying premium placed on virtuosity formed the basis for teaching music, especially piano, not only in newly established American musical conservatories, but among private teachers as well. Increasingly common throughout the mid to late nineteenth century was the trend to turn amateurs into performers. The goal of music teachers was to produce the virtuoso.

Since most piano pupils were female because music lessons were considered essential to their education and social graces, such a music teacher was as inevitable in the life of a well-brought-up child as was castor oil. As one historian points out, “the American ‘piano girl’ was a recognizable type” by 1840.6 But as one teacher admitted, “Taking lessons on the piano had no equals in the realm of torture.”7 Though few prescribed the mania with which Hans von Bülow practiced (“I crucify, like a good Christ, the flesh of my fingers, in order to make them obedient, submissive machines to the mind, as a pianist must”8), most professional pianists—who inevitably also taught—did follow Mendelssohn’s dictum: “Progress is made by work alone.”9 Piano instruction in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America followed the so-called “Klavier Schule” of Siegmund Lebert and Ludwig Stark, coauthors of the historic Method (1858). Descendant of the Czerny-Clementi-Reineke school, the Klavier Schule became standard in the United States as German pianists drilled in the method came to this country seeking disciples.10 By 1884 the Method was in its seventeenth American edition and had been expanded to four volumes. Though it was imported from Europe, it was exactly suited to the American work ethic and glorification of the virtuoso.

The main objective of the Klavier Schule was strengthening the fingers by rigidly playing studies, scales, and exercises “with power and energy.” This demanded practice of several hours a day, regardless of whether the pupil aspired to a concert career or merely enhanced social graces. As Ernest R. Kroeger asserted, “the piano was a steed to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Chapter One: The Place of Music in the Victorian Frame of Mind

- Chapter Two: The Origins of a Musical Democracy

- Chapter Three: Halcyon Years of the American Piano Industry

- Chapter Four: Strategies of Piano Merchandising

- Chapter Five: Industrial Bankruptcy in a Musical Age

- Chapter Six: Depression, Reform, and Recovery

- Epilogue The Piano—Symbol of a Past Age

- Appendix

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index