![]()

I

THE ROOTS OF A MUSICAL GENRE

Alexandria, Indiana, April 3,1996

The red-and-white-striped tent where we have gathered to eat is big. And the people inside it seem larger than life to me. There’s James Blackwood, along with his sons, Jimmy and Billy … there’s been a Blackwood in the gospel music industry since 1934. There’s Hovie Lister, the founder of the Statesmen Quartet, and Howard and Vestal Goodman of the Happy Goodman Family. There’s Jake Hess and Rex Nelon. Over in the corner is J. D. Sumner, the lowest singing bass singer on record and probably gospel music’s most recognized personality long before he and the Stamps joined Elvis Presley on tour in the early 1970s. The list seems endless … Brock and Ben Speer, along with their sisters Rosa Nell and Mary Tom, Lily Fern Weatherford, Glen Payne and George Younce, Naomi Sego, Les Beasley. They’re all here … along with a younger generation of gospel singers—Terry Blackwood, Jessy Dixon, Sue Dodge, Kirk Talley, Ann Downing, Gerald Wolfe, Kenny Bishop, Janet Paschal, Ivan Parker … far more than I can comprehend in one setting. Gospel singers all and each one here as guests of Bill and Gloria Gaither, themselves a part of the gospel music world for more than three decades.

The singers are here to record footage for more of Gaither’s Homecoming video series. I’m here to observe and meet as many as I can … to get their stories, to experience their struggles, to understand their dream. It is insight into a world I have known all my life … though only from the outside. Now I am inside … inside, under the tent, where the memories flow and the ancient songs are sweet.

![]()

1

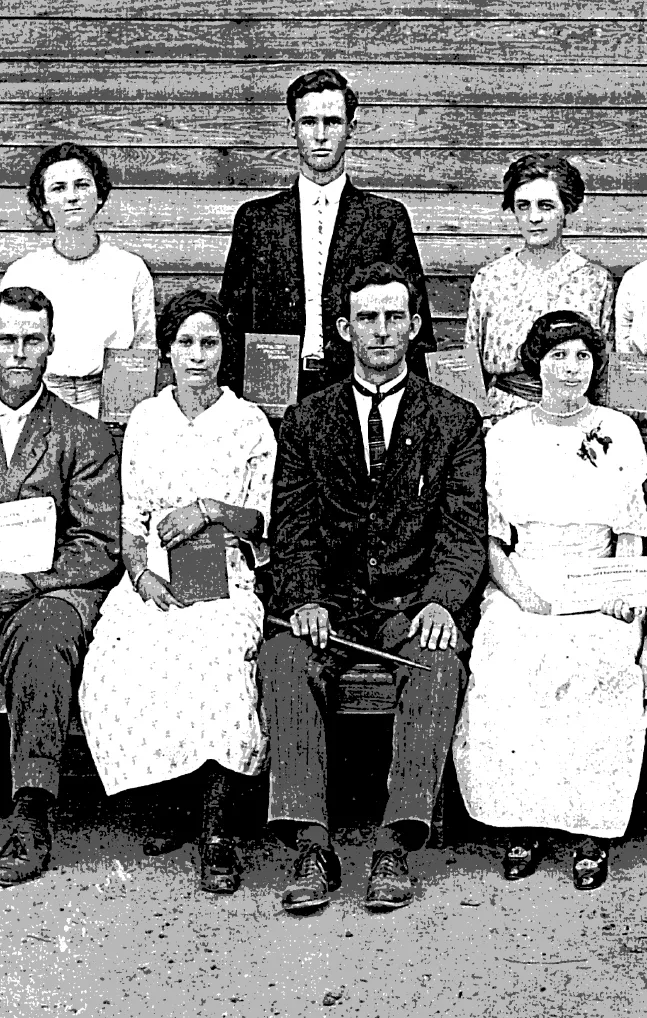

GOSPEL MUSIC IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Like most successful innovations in twentieth-century America, the gospel music industry emerged from a combination of forces that coalesced in the nineteenth. A revival of religious faith that stressed personal experience, a reform attitude that sparked among other things an interest in improved literacy within the population, a continuous fascination with transportation advances and the resulting ease of communication between one region and the next—all these factors helped define the character of nineteenth-century America and, thereby, contributed to the nation’s destiny. Whatever Americans became over the course of that century, they did so with the belief that they were somehow irreparably changing the course of history as they knew it. Despite the awesome nature of this conviction, Americans of a century ago remained remarkably confidant that they would succeed in building a great nation and that descendants would praise their efforts.1

Yet before the heady accomplishments of nineteenth-century Americans, earlier American settlers had begun the trends that would set into motion the limits of America’s religious music culture. American colonists inherited the worship traditions of Protestant Europe and, as a result, focused much of their energy in the early seventeenth and eighteenth centuries on the proper use of scripture in musical form. The oldest tradition in Christian hymnody was singing the Old Testament Psalms, a heritage that limited creativity among church musicians but that allowed for little debate on the issue of lyrical content. The earliest American Psalters arrived already bound within the Bibles of the Pilgrim colonists in 1620. A similar Psalter arrived with the more numerous Puritans who settled the Massachusetts Bay colony beginning in 1630. In response to some concern over the proper translation of the Psalms, settlers in Massachusetts soon enjoyed the publication of a new Psalter all their own when, in 1640, The Bay Psalm Book became “the first book-length product of a printing press in British North America.”2 Even with the presence of the new Psalter, Psalm-tunes were oftentimes “lined out,” a method by which the song leader would recite one or two lines and then have the audience chant the same words back in a songlike fashion. The method became even more prominent as rural churches formed in the backcountry and copies of the Psalter were neither easily available nor affordable.3

Always conscious — and to some degree self-conscious — of the colonial link to European culture, New England ministers pushed for improved musical ability among their congregations in a movement begun in the 1720s. Advocates of what was known as “the singing school movement,” or the “singing school war,” feared a loss of musical ability and pointed to the increased and almost exclusive use of “lining out” in some Puritan churches. Others feared the disappearance of good music itself. One New England minister, Thomas Walter, strongly pledged his support of the singing school movement, noting that Sunday singing in area churches produced “an horrid Medly [sic] of confused and disorderly noises.”4 The venerable Puritan spokesman Cotton Mather himself endorsed the musical improvements, which focused essentially on teaching a larger percentage of parishioners to read music.5 Opponents, on the other hand, feared that singing societies would detract from the serious nature of rational worship and accused proponents of being too concerned with frivolous trappings and ornamental aspects of the service. The New England “singing war” had some success in establishing local singing societies and generally seems to have contributed to the earliest elements of popular congregational singing in America.6 The impact of the singing societies was considerable, and, by the early 1700s, the movement had begun to make its influence felt even in the few Anglican churches of the remote southern colonies.7

Americans were also affected by the innovative musical contribution of Isaac Watts (1674-1748), perhaps the most influential of English songwriters. Watts introduced diversity into the English worship service by taking a broad approach in translating the message of the Psalms and, subsequently, broke with the Psalm-only tradition entirely in composing religious hymns for singing. Incredibly varied and abundant, Watts’s works became the best loved of the early American hymns and were included subsequently in almost every collection of religious songs published.8 Other innovative Englishmen, most notably John and Charles Wesley, continued the tradition and wrote songs designed to deepen the spiritual commitment of the earnest believer. By the time of the American Revolution, Americans were quite familiar with the concept of religious hymn singing as a separate part of the weekly worship service.9

But Americans would ultimately chart their own course in political and spiritual matters. Within a generation after political independence, a series of revivals erupted initially in scattered New England congregations in the 1790s but, most prominently, in the frontier communities of the trans-Appalachian West in the first few years of the nineteenth century. These revivals, which thrived in some areas until midcentury, ultimately shaped the character of American religion more than any single factor before or since.10

The revival spirit of the early nineteenth century occurred alongside perhaps the most creative period in American history. As the Revolutionary generation died out, a new generation of Americans sought meaning in the everyday experiences of building a nation. More than any other generation, they struggled with the definition of America and with what its citizens would aspire to become. As a result, the next half century would be spent redefining the context of democracy and citizenship, inaugurating a dizzying array of reform programs, and—just as important—experimenting with new ways of religious expression.

One of the most significant developments of the religious revivals was the birth of evangelical theology. Consistent with the drift of individualism and democratic government, evangelicalism came to embrace the view that personal salvation was a matter of individual choice, where, regardless of how it might be explained theologically, human beings shared at least some of the responsibility for initiating the process of conversion. In addition, evangelicals were certain that, once personal salvation had been secured, individual Christians would go about the business of changing their world from a den of iniquity into a kingdom of righteousness. Those two major impulses, individual choice in Christian salvation and active participation in social improvement, stood at the root of much of the reform spirit of the early years of the century. It was an exciting time, a moment of unparalleled restlessness.11

The Great Revival found its most unique expression in the areas of the American landscape least tied to either Europe or the colonial heritage. On the isolated frontier of Kentucky and Tennessee, men and women of all races came together to praise God and worship in an excited frenzy unmatched in American history. By the time revivalism reached a crescendo in midcentury, membership rolls in evangelical-style Protestant denominations had mushroomed and the cultural influence that these churches held over some regions and communities likewise increased. The biggest organizational benefactors were the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians, the overwhelming majority of whom adjusted both their theological views and worship practices to express the message and conform to the method of evangelical revival.12

The growth in membership of these Protestant organizations during the nineteenth century, particularly in the formerly unchurched South, was nothing short of amazing. Southern Presbyterians, numbering 20,000 in 1790 doubled in number by 1813 and topped 160,000 by 1835. Baptist churches enjoyed a similar growth pattern, moving from a membership of little more than 40,000 to almost 300,000 over the same period. By the end of the century, members of the Southern Baptist Convention alone would number more than 1,101,000. Methodists experienced the largest organizational growth. Separated from the Anglican Church in the 1780s, the Methodist Church in the South grew in membership from just over 40,000 in 1790 to well over a million by the conclusion of the Civil War. By the 1890s, black and white Methodists and Baptists in the South combined totaled between 4.5 and 5 million adherents.13

The center of the revival activity in many rural areas was the camp meeting, an extended festival of religious worship in which most Protestant denominations represented in a given area participated. Coordinated best and most often by Methodists, these four-to seven-day camp meetings became events of considerable social significance quite apart from the measure of religious significance they held. In remote areas where neighbors saw each other infrequently at best, the camp meeting flourished as an annual event held in conjunction with a lull in the agricultural calendar. No camp meeting achieved a greater legacy than the Cane Ridge Camp Meeting begun in 1801 in Bourbon County, Kentucky. Originally planned by area Presbyterians as a communitywide communion service, the meeting tapped into an already brewing revival spirit. Drawing crowds in excess of 10,000 during the earliest years of the century, Cane Ridge became famous for the emotional freedom that many worshipers demonstrated as they shouted and danced under the influence of religious power.14

Among the many activities enjoyed in the camp meetings, singing proved to be one of the most influential.15 Around evening campfires both before and following the preaching service, devout followers gathered to sing their favorite hymns. Especially popular were the choruses, many of which were constructed specifically to adjoin traditional hymns with which worshipers were already familiar.16 Choruses were popular for several reasons. They tended to be catchy tunes that were easy to sing and thus easy to learn. Not coincidentally, they were often constructed from popular folk melodies that were already well known to many in the audience. In addition, they solved in one step the dual problem of illiteracy and a shortage of songbooks. A handful of individuals with books or with small collections of song lyrics called songsters could sing the verses while the bulk of the participants joined in on the chorus.17

Memoirs of the great camp meeting days invariably recall the centrality of music and credit the songs with much of the spiritual atmosphere that the meetings were able to engender. A participant at Cane Ridge remembered that a “serenade of music cheered all their spirits, which never desisted from their first happy coalition, until they decamped, and everyone sung what he pleased, and to the tunes with which he was best acquainted.”18 Within a few years of the eruption at Cane Ridge, many Presbyterians and Baptists grew lukewarm about their participation in the annual camp meetings. Concerned about what ma...