![]()

1 Cille Pheadair and the Norse period in South Uist

M. Parker Pearson

The machair plain, a zone of shell sand, on South Uist’s west coast is known to have been densely settled in prehistory and in the historical period. Some of the first traces of this rich cultural heritage were brought to light by Tom Lethbridge in the early 1950s when he and Werner Kissling discovered numerous ancient settlement mounds on the machair of Cille Pheadair (Kilpheder) township.1 Cille Pheadair is located in the southern part of South Uist (Figure 1.1), about 6km from its south coast and 1km south of the modern community of Dalabrog (Daliburgh). The low machair plain of the southern end of the island gives way here at Cille Pheadair to a more hummocky terrain with high sandhills and dunes that characterizes the west coast from Cille Pheadair to Cill Donnain, 8km to the north (Ritchie 1967). The machair extends along most of the 33km-long west coast of South Uist and is generally about a kilometre in width east–west.

The site at Cille Pheadair is separated from the peatlands to the east by a former loch that is now dry and drained. In prehistoric times this loch was a cockle strand connected to the open sea through an inlet immediately to the south of Cille Pheadair. The machair here was thus a thin peninsula perhaps as much as 7km long, comparable to the present-day coastline of Baile Sear on the west coast of North Uist.

Although the machair in the southern part of Cille Pheadair township is largely without large hummocks or dunes, it is fronted on its west side by a long coastal dune with a steep west (seaward) face and a gentle eastern slope. The coastal dune is cut by the wind and sea into a vertically-faced sand cliff that runs north–south; a bank of storm-deposited cobbles lies at the base of the sand cliff, with a sandy beach beyond, interrupted by expanses of rock outcrops in the shallow water below the low tide line.

The Norse-period farmstead of Cille Pheadair (Site 66 in the machair survey2) was entirely buried beneath this coastal dune, covered by over 3m of windblown sand, so that no part of this deeply buried site was visible on the ground surface for probably many centuries. It had also been thus protected from burrowing by rabbits. About 70m to the south of it, not far from the former inlet to the dry loch, a Pictish burial cairn was similarly buried beneath 2m of coastal dune. After high-tide storms in the winter of 1993/1994 two brothers, Calum and Seumas MacDonald, discovered the Norse-period farmstead site, visible as a 1m-deep sandwich of grey soil and stones between thick layers of white sand, running for a length of about 40m in the sand cliff above the beach.

With a rate of erosion of this coastline estimated at about 20m–25m in 25 years, it was clear that about a metre of the western edge of the site had already been destroyed and the remainder was directly under threat from the sea. Since the provision of sea defences for this particular location, within a much longer eroding coastline, was clearly inappropriate and impractical, a rescue excavation was carried out over a total of five months during the summers of 1996, 1997 and 1998, funded jointly by Historic Scotland and the Universities of Sheffield, Cardiff and Bournemouth. The site has since been entirely destroyed (see Parker Pearson 2012c).

1.1 Previous research in Cille Pheadair township

Kissling and Lethbridge at the Kilpheder wheelhouse

Although the archaeological richness and potential of North Uist’s machair coast was demonstrated as early as the turn of the twentieth century by Erskine Beveridge (1911), in contrast South Uist’s machair was largely under-researched until the second half of the century. Even the Royal Commission’s (RCAHMS) inventory of 1928 recorded just a handful of sites in this zone, compared to the many duns, brochs, church ruins and other sites of the central peatlands and eastern hills.

One of the more remarkable stories of the Uists in the twentieth century is that of Werner Kissling, an émigré German, formerly a diplomat, who had fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s (Russell 1997). He is principally remembered for his film of everyday life on Eriskay and for his research into the ‘blackhouses’ of the Western Isles. Some ‘blackhouses’ were still being lived in when Kissling arrived in the southern isles in the 1930s, and Kissling was interested both in their stark architecture and in their use in the islanders’ economic regime of agriculture and fishing. Kissling was also interested in archaeology, having been interned during the war on the Isle of Man with Gerhard Bersu, one of the greatest German excavators of the day (Evans 1998).

Figure 1.1. Map of the Western Isles, showing the location of Cille Pheadair and other Viking Age and Late Norse sites

These interests came together when Kissling invited a Cambridge archaeologist, Tom Lethbridge, to come and join him on South Uist. They discovered a large artificial mound (c. 5m high, c. 80m east–west and c. 50m north–south) on Cille Pheadair’s machair (Site 63; Parker Pearson 1996b; 2012c). Kissling hoped to encourage the local people to take an interest in their antiquities but his hopes of excavating the buildings inside this mound were dashed when the crofter of this particular piece of land, the late Angus MacClellan, refused permission for a dig. Kissling turned his attention to a second, smaller mound (Site 64) about 400m to the southwest; this mound was known as Bruthach Sitheanach – ‘the Brae of the Fairy Hill’ (Lethbridge 1952) – though RCAHMS recorded its name as Bruthach an Tionail Ard.

Figure 1.2. Angus John Campbell of Lochbaghasadal (left) and John Robertson of Harrapol standing within the hearth of the Kilpheder wheelhouse (from Lethbridge 1954: pl. 2 [a])

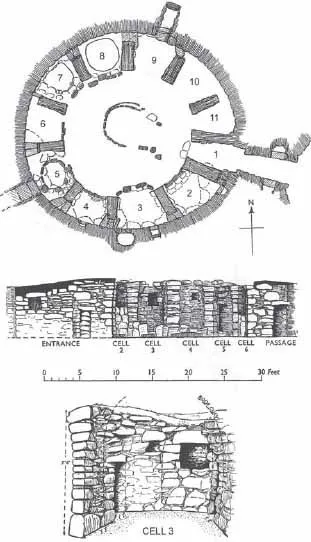

During the dry spring of 1951 Kissling and Lethbridge noticed that outlines of circular walls could be detected as parchmarks in the grass over this mound. This was one of three circular buildings that Lethbridge identified from parchmarks, confirmed by geophysical earth resistance survey of the mound in 1998 (Parker Pearson 2012c: 50). That summer, which was remembered as being exceptionally hot and dry, Kissling and Lethbridge employed a team of local men, supervised by John Robertson of Harrapol (Skye), to shovel out the deep infill of windblown sand (Figure 1.2). Kissling had extraordinary beginner’s luck because the stone walls and piers of the Iron Age ‘wheelhouse’ that he and Lethbridge discovered inside the mound were entirely intact to the base of the roof, almost 2.5m (8ft) above the floor (Figure 1.3). In no excavation before or since in the Western Isles have archaeologists found buried remains of prehistoric houses so completely preserved.

A Roman brooch found on the ledge of one of the house’s wall chambers indicated that the house might have been abandoned around AD 100–150. The excavation also recovered pottery sherds, bone tools and an iron pin fragment from inside the house (Lethbridge 1952). In their styles these artefacts are of types now dated to the Middle Iron Age, between c. 200 BC and c. AD 400 (Armit 1996: 145–8; Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999: 359; Sharples 2012a: 17).

The following summer, limited excavations continued immediately outside the south side of the wheelhouse to reveal a smaller round building that was joined to the wheelhouse by an underground passage. When the excavation ended the interior void of this round outbuilding was filled in but, unfortunately, the wheelhouse was not. This magnificent roundhouse should have been either reburied or consolidated by shoring and pointing; in the last 60 years, its walls and internal stone piers have largely collapsed and the visitor is presented today with a large hole filled with fallen stones. Local opinion today is that the Kilpheder wheelhouse should be consolidated for better public access and understanding.

Figure 1.3. Plan and elevation of the Kilpheder wheelhouse (from Lethbridge 1952)

The 1951 excavation is still remembered by local residents now approaching old age; Kissling himself was evidently a dynamic personality since there are still local memories both of his supervision of the workmen and of the swimming lessons and races he organized for the local children. Tom Lethbridge published the results of the 1951 season in the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society in the following year but, curiously, by the 1990s nobody remembered his presence on the excavations.3

The reason why the Kilpheder wheelhouse – and presumably its neighbours within the mound – is so well preserved is worth considering. Every other prehistoric or later house that has been excavated on the machair has been robbed of its stones, mostly in the years immediately after abandonment. In some cases, that robbing is intermittent and partial and in others it is near-total. The reason, no doubt, is that building stone for any structure had to be brought onto the machair, either from the beach or from the hills some four to ten kilometres to the east. The Kilpheder wheelhouse’s fabric consisted of large and partially shaped stones from the hills. This was masonry that would have been highly sought after for building and yet this structure was left intact.

We might speculate, then, that the three houses within this mound were dramatically engulfed by windblown sand and deeply buried before anyone had a chance to remove their stonework. Yet even this scenario seems unlikely, given that Lethbridge records how clean the wheelhouse floor was. He wrote that even the hearth had been swept clean before the house was abandoned (Lethbridge 1952: 180). He later speculated that the clean hearth and floor, together with various artefacts left in wall niches and on the floors of the cells between the piers (an antler pick, a piece of pumice, an awl, a quartzite strike-a-light and a horn ferrule as well as the brooch) indicated that the inhabitants had gone away and never returned (1954: 68–9). Our excavations of other house floors of similar date at Dun Vulan (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999), Bornais (Sharples 2005d; 2012b), Cill Donnain (Zvelebil 1991; Parker Pearson and Zvelebil 2014) and Cladh Hallan (Parker Pearson et al. 2004a: 59–87; in prep.) – where the floors and hearths were anything but swept and clean – reveal that Lethbridge’s diagnosis was indeed correct. So how do we explain why the buildings were left untouched?

The Kilpheder wheelhouse appears unusual in that it had its floor and hearth swept and its roof removed before abandonment, being then left untouched until it had been entirely covered with sand. The Roman brooch left on one of the ledges is also unusual because it is one of the very few Roman manufactured goods imported into western Scotland at that time (Armit 1996: 160–1; see Sharples 2012b: 19, 339). At some time in the second century AD, this house – and probably the entire group of wheelhouses in the mound – was abandoned and left untouched. We may speculate about the possible reasons why. Was it a plague house, abandoned after catastrophic illness and death, like one of the nineteenth-century blackhouses at Balnabodach on Barra (Branigan 2005)? Was it a house that had been associated with some unsupportable event or action, such as witchcraft? Perhaps a violent act occurred there or a tragic death such as drowning overtook its inhabitants. Or were the inhabitants driven out because of the loss of their livelihood or through forced relocation?

The mound into which Kissling and Lethbridge were not permitted to dig (Site 63) dates broadly to the same period of the Middle Iron Age as the Kilpheder wheelhouse, on the basis of pottery found during surface survey, although some sherds recovered from Site 63 are of a type found on the floor of the wall chamber at Dun Vulan and dated to between the first century BC and the second century AD (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999: 92, fig. 4.13.1, 9 and 10), making this mound perhaps slightly earlier than the Kilpheder wheelhouse. Paradoxically (and luckily for Kissling and Lethbridge), it seems from the results of our geophysical survey (Parker Pearson 2012c) that the mound of Site 63 contains no similarly complete buildings.

The long-term settlement sequence at Cille Pheadair before the Viking Age

Lethbridge considered that Kilpheder was just one of nine Middle Iron Age wheelhouses within this particular part of South Uist on Cille Pheadair and Dalabrog machair (1952: 177). Unfortunately his map is at too small a scale and his dots too large for these proposed sites to be relocated precisely. He does, however, provide locations for five of them in the text (ibid.: 176). From his descriptions, four of these mounds date to the Middle Iron Age but he seems to have found no dating evidence for the other five. From our own survey and those of others we can now identify a total of 27 prehistoric settlement mounds in this area – 18 on Dalabrog’s machair and nine on Cille Pheadair’s machair (Figure 1.4; see Parker Pearson 1996b; 2012c).

Although most of the machair is covered by grass, ancient settlement mounds can be identified in unploughed areas by the presence of marine shell (usually limpets and winkles, but also cockles, mussels, etc.), animal bone and sherds in the spoil produced by rabbit burrows and in scoured and eroded areas. Those settlement mounds currently being ploughed also produce similar materi...