![]()

Part I

Introduction, Methodology, Summarizing the Data, Discussion

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1. How Is this Study Organized?

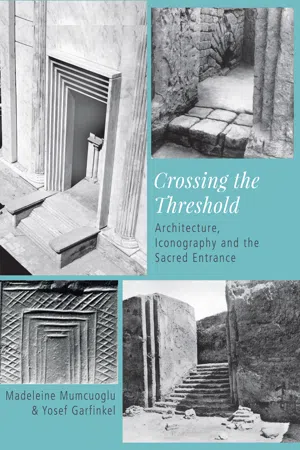

This monograph is dedicated to recessed doorframes or window-frames from the ancient Near East, the Mediterranean basin, and Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and later cultures until the modern day. As we will demonstrate, the fashion for decorating important entrances with a recessed opening prevailed for nearly 6,500 years. No other architectural symbol in human evolution displays such durability or vitality. Given this fact, it is surprising that the subject has been neglected for so long by archaeologists and architects. To date there is not a single monograph, or even article, specifically dedicated to the subject of recessed openings.

Our presentation here is organized in two parts. The first part comprises the introduction, methodology and discussion. Here the various research questions are presented and discussed, affording the reader an overview of the subject. In the second part of the book the relevant data is presented in nine chapters, each dedicated to a specific era and region. The chapters are organized chronologically, from the oldest to the most recent. The data is presented in text with accompanying illustrations: geographical maps, excavation maps, photographs and drawings. Since the subject we are analyzing here is a visual motif, it is essential to provide pictorial representations of the various examples.

Recessed openings are known as early as the Late Prehistoric era in Iraq, dated to the middle of the fifth millennium BCE. In the earliest examples, recessed openings were constructed at the entrances to temples. Later, in the third millennium BCE, they were occasionally integrated into the architecture of royal palaces and royal graves. In a later phase, the first millennium BCE, they were extensively used in grave architecture. Recessed openings of doors, sometimes even windows, were depicted in the ancient Near East on various steles, building models, ivories, cylinder seals and other art objects.

Recessed openings are also mentioned in ancient literary compilations, such as biblical descriptions of Solomon’s Palace and Temple, and in descriptions of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Roman architect Vitruvius described recessed openings in relation to the Ionic order in his writings on architecture.

Recessed openings were adapted to Classical monuments and are known in various Greek, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine buildings and graves. They retained their appeal in medieval Romanesque and Gothic architecture and can still be seen in some modern buildings today. As our focus here is the ancient Near East, where the motif originated, most of our examples are drawn from that early period or soon after. The later history of recessed openings is briefly presented, in order to give the reader a comprehensive picture of this unique motif in human history.

Recessed openings reflect ways of representing the sacred and of thinking about social organization in stratified societies, access to public buildings and liminality between the mundane and the divine worlds. In our discussion of the motif, we considered historical, anthropological, sociological, religious and economic factors according to the longue durée concept (Braudel 1958). In doing so we hope to achieve a synthetic analysis, since factors such geography and social patterns are more important than events (Purcell and Horten 2000). According to Dupront, who espouses the longue durée idea, the study of a religious fact allows one to reach into the collective sub-conscious and imagination. His studies of the sacred, pilgrimages and crusades: Du Sacré, croisades et pèlerinages. Images et langages, demonstrate his multidisciplinary approach to history, utilizing tools from psychoanalysis, anthropology and philosophy (Dupront 1987).

Braudel states (2009): “Each of us has the sense that beyond his own life, there lies a massive historical past”. A clear example of this claim is manifest in recessed openings, a tradition that was passed down from generation to generation, surviving intact until today.

1.2. The Research Questions

Our study was organized around eight research questions, listed here in the order in which they are later discussed. For the benefit of the reader, the section that answers each question is mentioned in brackets at the end of each point:

1. How are recessed openings represented? What types of evidence indicate their existence and use? (Section 3.1)

2. Chronology: When were recessed openings invented, and for how long were they in use? (Section 3.2)

3. Geography: Where were recessed openings used, and how did their use spread over time? (Section 3.3)

4. Are recessed openings a local development in each region, or did they spread from one center to other regions? (Section 4.1)

5. Evolution: How did the use of recessed openings change over time and space? (Section 4.2)

6. Architectural strength: What are the advantages of recessed openings as a medium of architectural decoration? (Section 4.3)

7. Social value: How were the social order and social organization reflected in the use of recessed openings? (Section 4.4)

8. The sacred: How were ideas about religion and the sacred reflected in the use of recessed openings? (Section 4.5)

These aspects are not distinct from one another. Nevertheless, emphasizing a specific aspect at a time helps to describe and analyze the data presented in Part II of this study.

1.3. Definition of Recessed Openings

Doors or windows are openings in walls which by their mere existence create an interruption in the wall in which they are constructed. Most of the walls around doors or windows end in straight simple lines. In elaborate architecture the edges of the wall around doors or windows were sometimes designed with a recessed pattern. The recess is part of the wall, the edge which is located adjacent to a door or window.

The word recess derives from Latin “recessus”, a retreat, from recedere to recede. The recessed pattern is created by narrowing the thickness of the wall around the opening in even stages, parallel to the opening sides, creating stepped, interlocking frames, one inside the other. The opening itself is located inside the smaller frame, in the deepest part of the entrance. This pattern usually creates vertical step-like images on the left and right sides of an opening and horizontal step-like images above the opening. In arched openings the step-like image is sometimes rounded. The recessed pattern is created by indentations set further back than the outer face of a wall, placing the opening itself in the deepest location inside the wall. The recessed sides create a frame around an opening with the repeating element of a frame inside a frame inside another frame, usually three times, but sometimes more.

In wooden constructions this is known as rabbeting, and is obtained by fitting together several receding doorframes. As wood decays over time, it is not possible to find historical examples of such wooden frames.

A similar phenomenon is called moulding, an embellishment in strip form, made of wood or other structural material, which is used in buildings, walls, doors or furniture. It is a decorative strip used for ornamentation or finishing. Mouldings around a door or a window are called architrave. Ramsay and Bell (1909:472–489) dedicated a long discussion to moulding and its development over time in Byzantine architecture in the Dead Cities of Syria (below, Nos. 183–186).

In ancient Mesopotamia, the number of recessed frames varied from one to three with exceptions such as a temple with six frames at the site of Basmusian (below, No. 69). The construction of the recess sometimes corresponds to the thickness of the wall and the size of the bricks used. Thus, halved or quartered bricks, of the same thickness as in the wall itself, were commonly used. Recesses of a few centimeters in thickness are also known. When other building materials, like stone and marble, were introduced, the recesses were sometimes reduced to less than a centimeter in thickness. It is then difficult to differentiate between mouldings and recesses.

There were other ways to embellish doors in ancient architecture. The fifth millennium BCE temple of Ein Gedi, in the Judean desert, was built with the sides of the opening protruding outside (Ussishkin 1980). This, however, does not create a recessed opening. In the same way, a building model from the third millennium BCE city of Arad has an emphasized opening, albeit not organized as recessed frames that become smaller toward the opening (Amiran 1978, Pls. 66, 115). In ancient Egyptian architecture, false doors were quite often emphasized by the use of various interlocking frames (Arnold 2003). These, however, did not get systematically narrower toward the door, and they sometimes protruded to the outside.

In this work we will concentrate on double or more recessed openings. A single recessed opening will not be taken into account as a decorative element since it could simply be a practical detail to allow the door to fit in the opening, rather than an embellishment.

1.4. Recessed Openings: History of Research

Examples of recessed openings in the ancient Near East were found in numerous excavations in the early stages of systematic archaeological excavation in the area. The phenomenon was reported as early as the mid-19th century on miniature Phoenician ivories from Nimrud decorated with the famous “woman at the window” motif (below, Nos. 128–132). Four such ivories were unearthed, described as “represent[ing] a kind of window with three plain mouldings” (Layard 1849). Toward the end of the 19th century, life-size recessed openings were uncovered at the royal graves of Tamassos in Cyprus (Ohnefalsch-Richter 1895).

Ward noted recessed openings in the iconography of cylinder seals depicting Mesopotamian temples even before such temples were actually reported from archaeological excavations in that region. In his analysis of cylinder seals with shrines and animals, Ward wrote: “. . . the form of the grand entrance, or gateway, is clearly shown. The central door is in a somewhat deep recess apparently, as it very frequent now in the East, where the visitor is protected from rain by the depth of the wall” (Ward 1910:180), adding: “The shrines, or doorways, on these cylinders . . . seem to suggest, perhaps, a door with a recess in the wall” (Ward 1910:182). Ward did not, however, recognize the same motif on cylinder seals when it appeared as a stool with interlocking frames, the throne of a seated god (Ward 1910:108–114, Figs. 303, 305, 313, 321). Another extensive work on cylinder seals published the same year also fails to recognize this attribute (Delaporte 1910).

Only in the 1920s and 1930s were recessed openings of life-size buildings uncovered in many Mesopotamian sites, like Tepe Gawra, Khafajah, Tell Asmar, Ur, Mari and others, as will be discussed below. The widespread occurrence of this phenomenon throughout Mesopotamia was observed by the great scholar Henri Frankfort: “The ornamentation by means of recessing is another common feature of sacred architecture in the north and in the south” (in Delougaz 1942:299–312). Depictions of recessed windows were also found in these years on ivories uncovered at the sites of Arslan Tash and Samaria (Thureau-Dangin et al. 1931; Crowfoot 1938).

The effect of these discoveries on biblical scholars can be seen around the middle of the 20th century. Yadin (1956), S. Yeivin (1965) and later Noth (1968) pointed out that recessed patterns in Mesopotamian architecture and Phoenician ivories could be used in order to decipher biblical terms relating to Solomon’s Temple. Yeivin’s Hebrew publication of this finding (1965) was largely overlooked by scholars. Recessed doors appear in many contemporary reconstructions of Solomon’s Temple (see, for example, Hurowitz 2009, 2010), but are not universally recognized (Cogan 2001).

In 1975 Barnett summarized: “The triple recessing around the door goes back originally to a decorative feature in the most ancient temples in Babylonia, the recessed exterior niche which, when it appears in a single rectangular form, seems to have been well understood as an abbreviated sign for a temple. In actual use to frame doorways it is regularly used in temple architecture from earliest period until Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times and the tradition is taken up in Achaemenid art” (Barnett 1975).

In a detailed study dedicated to doors in ancient Mesopotamia, Damerji discussed various types of door and gate. His third category is defined as: “Wall interruption with rabbeting outside” (Damerji 1987:68–70). The recessed character of this category is described as: “This feature in door architecture is by no means a building necessity but rather a decorative element that was established at least in early architectural phases (in Mesopotamia), for entrances of temples or buildings treated as religious. It is valid also for later phases that in almost all examples, the rabbeted edge is reserved for these kinds of buildings. It is not used on all doors, but in prominent ones” (Damerji 1987:68).

In her dictionary of ancient Near Eastern architecture, Leick relates to this phenomenon. She defines a recess as “a part of the wall which is set back from the main surface. In the context of Mesopotamian architectural decoration, recesses are vertical grooves with curved or rectangular prof...