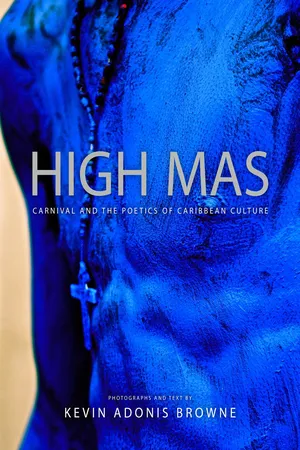

![]()

——— SERIES ———

SEEING BLUE

For all the seeing it can enable, this craft is one of conjuring our missing pieces—pieces missing from the start, or shortly after it. It is the collection and tenuous resetting of broken bones and of kept, forgotten pieces. It is a conjuring up of missing things that cannot be bestowed with sight alone, but also with vision. It’s what’s required to see what exists beyond the boundary of the frame and beneath the mystery of unexplored shadow. Emerging from a need to respond to the ubiquitous stain of Empire, it does not memorialize, nor can it create what is not there to be seen. (In time, you will see that neither Mas nor this craft will allow those things.) It is, rather, the art of memory’s inadequacy, the declaration that there is something worth remembering, worth seeing, and worth looking for—and that it is gone away from you (returning, now and again, in parts, like a flawed lover to your mad and vulnerable days). We are here to embrace all of it, knowing we entangle ourselves as much in loss and missing as with challenges of sight.

—PARAMIN AND PORT OF SPAIN, 2014

Brandon “Redman” Reese picks up dollar bills with his mouth. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2015.

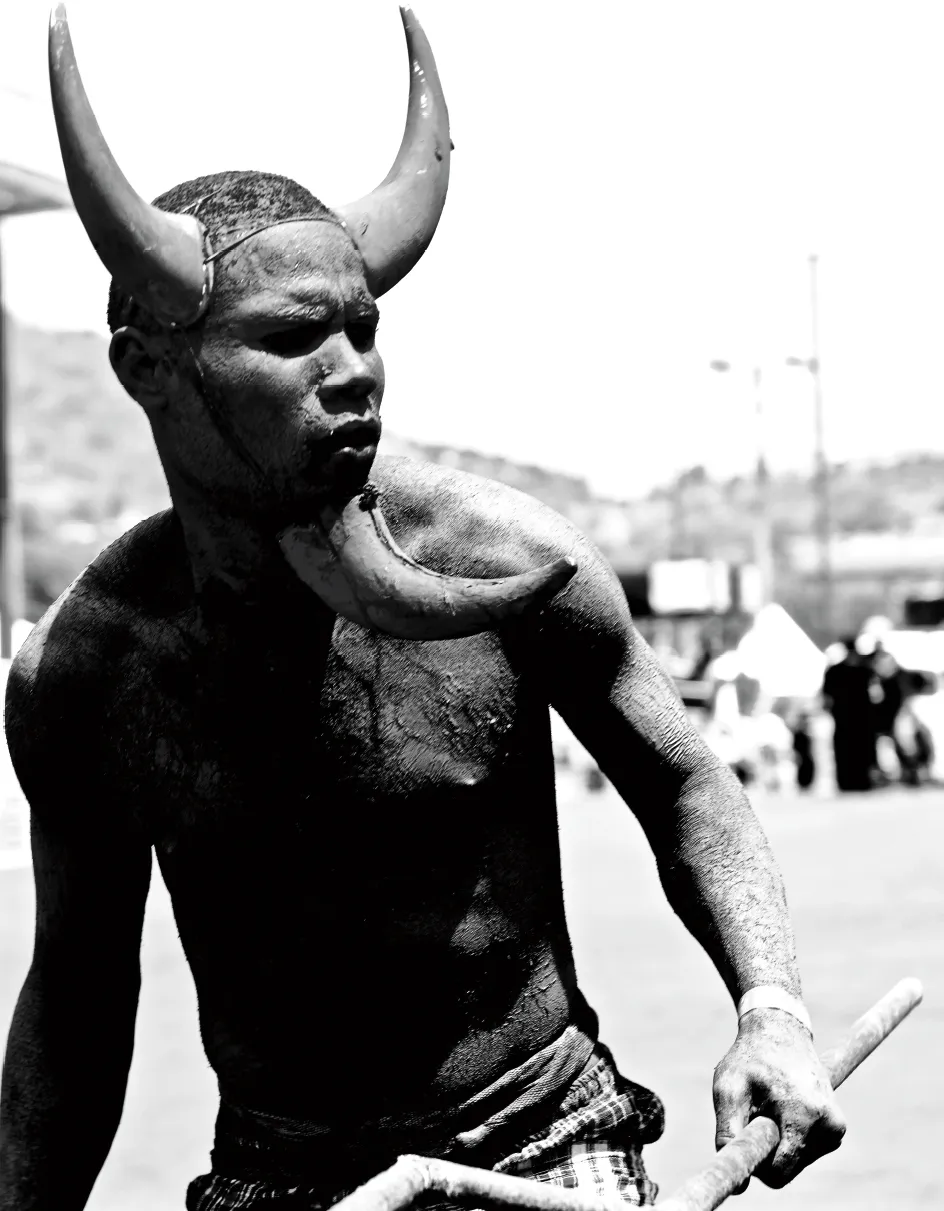

Ashton “Spooky” Fournillier, bandleader of the “Redhead Devils,” at Traditional Mas Competition at Adam Smith Square, Woodbrook, 2016

Steffano “Steffi” Marcano blows fire toward the Judges’ Area during Traditional Mas Competition. Adam Smith Square, Woodbrook, 2016

“Steffi” dances. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

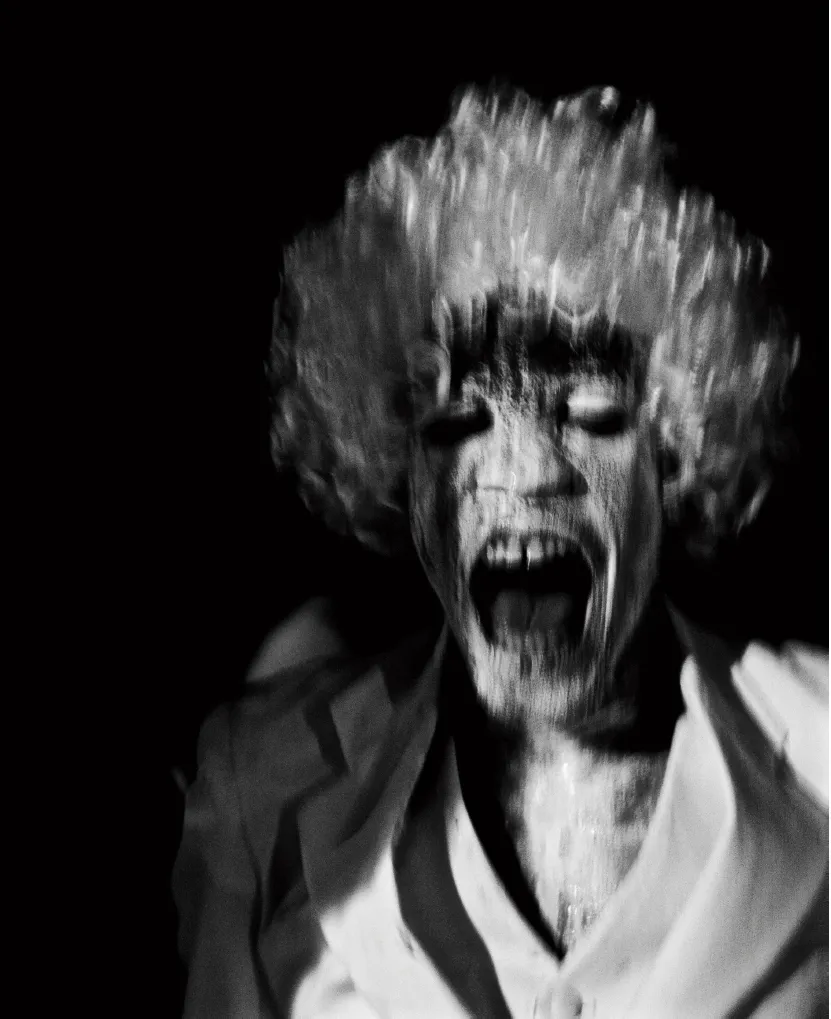

Deon “Froggy” Letren, known for “crying” before he blows fire. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Jeron Pierre, with face painted white and a mouth full of “blood” (red food dye). Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Alexie Joseph, Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014. First in a series of two.

Alexie Joseph, Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014. Second in a series of two.

“Steffi” reminds us that “all skin-teeth ent joke.” Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Jamal Joseph, after the last performance of the day. Adam Smith Square, Port of Spain.

“Steffi” at Traditional Mas Competition. Victoria Square, Port of Spain, 2014.

Alexie Joseph sprays fire. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

A boy (anonymous) in a wolf mask. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Brandon’s wirebended wings. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

A “Boy Wolf” held in check by an older, more experienced Blue Devil. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

“Froggy” blows fire from a flambeau (torch) after crying and pretending to pray to it. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

A dismembered baby doll, bloodied and blue. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

“Froggy” blows fire for the crowd, having gone through his extensive crying ritual. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

A Blue Devil holds a dollar on “The Avenue.” Ariapita Avenue, Woodbrook, Port of Spain, 2014.

Alexie Joseph applies paint to his face. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Ncosi Joyeau points at the lens, indicting and inviting the viewer to reflect. Ariapita Avenue, Woodbrook, 2014.

Syncretism of Catholic iconography and less obvious features of African and Hindu traditions that center (on) the body. Woodbrook, Port of Spain, 2014.

A refusal of access. Ariapita Avenue, Woodbrook, 2014.

“Steffi” dances. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

“Frenchy” crosses the main stage in the Queen’s Park Savannah, after competing throughout the city. Port of Spain, 2014.

Shane St. Hillaire attempts to interact with a distracted spectator. Victoria Square, Port of Spain, 2014.

Sharing a laugh after a performance, Emilio Constantine embraces himself. Adam Smith Square, Port of Spain, Trinidad, 2014.

“Spooky” blows fire for Traditional Mas Competition. Victoria Square, Port of Spain, 2014.

Shane St. Hillaire makes his presence felt on the Queen’s Park Savannah stage. Port of Spain, 2014.

Renaldo (“Uno”) offers an alternative to “begging” and other forms of materialism. Queen’s Park Savannah, Port of Spain, 2014.

Nigel Pierre, resting after the Queen’s Park Savannah performance. Victoria Avenue, Port of Spain, 2014.

“Steffi” feigning shock. Ariapita Avenue, Woodbrook, 2014.

Of seeing and of being seen. Queen’s Park Savannah, Port of Spain, 2014.

Tracey Sankar admonishes the photographer, or whoever she imagines will see the image. Port of Spain, 2014.

“Frenchy” at rest. Revellers revel, spectators spectate. South Quay, Port of Spain, 2014.

Roger Holder interlocks with a police constable. Piccadilly Greens, Port of Spain, 2014.

Amaron St. Hillaire, a Blue Devil painted in white, leads his group out of the darkness. Fatima Junction, Paramin, 2014.

Ricardo Felicien, a Blue Devil painted in white and sequined, during Traditional Mas Competition. Adam Smith Square, Woodbrook, 2016

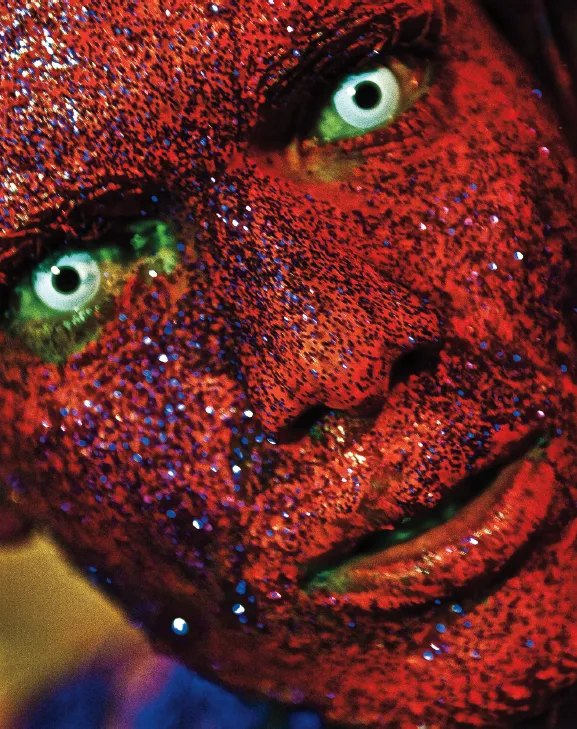

Andrew “Nykimo” Nicholas, another white devil, gets glittered for a performance in St. James Amphitheatre. St. James, 2017.

![]()

SEEING BLUE

Genesis of Public Executions

Note to a Self, Possessed

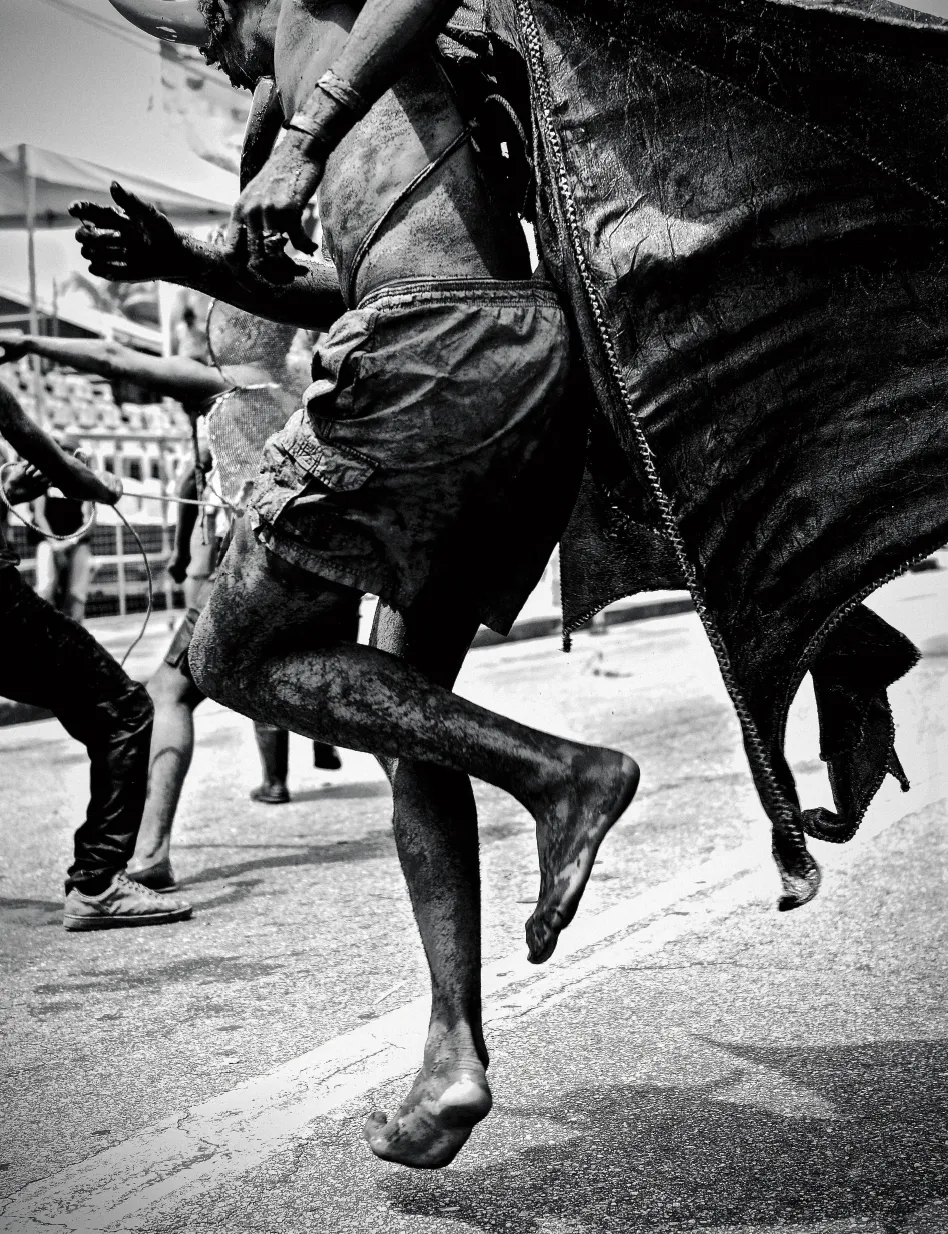

A screaming man is dancing. Bare. His chest and back and feet are exposed. His wireframe wings sway like mad counterweights to his light, frenetic step. Right to his left. Left to his right. His beauty and his artistry seem untamed, almost accidental. Carved, almost, from a single piece of Kapok wood.

Look.

He is dancing a familiar and vulgar reality of hard times and of pleasure, of sweetened suffering and of synchronized shadows—dancing in a way we have yet to learn. He is (as best you can tell) unapologetic. His band taunts him mercilessly, jabbing him with a rhythm beat on burned-out biscuit pans:

Pakpataktak! Pakatatakatak!

Pakpataktak! Pakatatakatak!

Pakpataktak! Pakatatakatak!

Pakpataktak! Pakatatakatak!

This rhythm is old (only an old rhythm will do for this dance), with little space for well-worn hands and insistent feet to evolve in the time that’s passed. He and others like him pour from the everyday obscurity of a Paramin dawn and into the harsh materiality of Port of Spain—a capital of common people. Their screams are the piercing throes of a culture fighting for its life—and losing, gradually—or maybe they are the sharpened sighs of a people who struggle to endure what blue can do to bare skin. It burns. Now, the screaming man is breathing fire. He spits out the excess before it bursts into flames too close to his tongue. Two more join him with their sooted flambeaux bottles and pitchforks of wood and PVC. They, too, know how power is imposed on their bodies and their tongues. It tastes like pitch oil, like cruelty refined. Bathed in it, the stench of a smoldering dump so close to the city is almost undetectable to you, though it casts a suffocating shroud over the people in Beetham, in Morvant, and in Laventille. It can, at times, stretch farther West, into Belmont. Farther still, toward rarified Glencoe and Carenage, where my grandmother is from. Behind the bridge, another pair of devils poses with other people’s children as if they were a family. They pretend to smile for the camera. Then they scatter, abandoning their borrowed children, blocking lenses, demanding attention and money. The drama in this collection of tithes is, I think, a perfected mockery of dreams deferred.

You are their photographer. They do not know, or seem to care, who you are. And why should they? You’ve been drafted in a rush. Although your vision will produce more failure than success, more frustration than peace, you take a certain pride in seeing what you think others cannot. Now, you wait for them, knowing they will make you pay for everything you see, that their coming heralds the return of an unease you usually keep hidden away.

Pakpataktak! Pakatatakatak!

Pakpataktak! Paka...