eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Dancing Bahia

Essays on Afro-Brazilian Dance, Education, Memory, and Race

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Dancing Bahia

Essays on Afro-Brazilian Dance, Education, Memory, and Race

About this book

Dancing Bahia is an edited collection that draws together the work of leading scholars, artists and dance activists from Brazil, Canada and the United States to examine the particular ways in which dance has responded to sociopolitical notions of race and community, resisting stereotypes, and redefining African Diaspora and Afro-Brazilian traditions.

Using the Brazilian city of Salvador da Bahia as its focal point, this volume brings to the fore questions of citizenship, human rights and community building. The essays within are informed by both theory and practice, as well as black activism that inspires and grounds the research, teaching and creative output of dance professionals from, or deeply connected to, Bahia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dancing Bahia by Lucia M. Suarez, Amélia Conrado, Yvonne Daniel, Lucia M. Suarez,Amélia Conrado,Yvonne Daniel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Teoría y práctica de la educación. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Bahian Dance in Action

Chapter 1

Afro-Brazilian Dance as Black Activism

Amélia Conrado

Figure 1: Map of Brazil.

Introduction

This essay outlines a brief historical background of African dance in Brazil and its importance for the struggles of blacks, both in the past and in the present. Racism and racial discrimination still exist in Brazilian society, and must be addressed and overcome as soon as possible. I draw from studies on education and black identity formation to show how dance can lead to significant black consciousness and consequently to a positive transformation of black people and the social attitudes of others. This essay examines the ways that black Bahians across several Brazilian states have engaged in their cultural practices, such as drumming sessions, rituals, and capoeira, as manifestations of ethnic identity and cultural resistance. Where the practices persist, they incorporate new aesthetic concepts and forms, which broaden the meaning of these cultural legacies without losing their origin purposes. In identifying many Afro-Brazilian dances, this chapter provides a sturdy dance background for concentration on Bahia and its seminal position as the activism and affirmation center of African legacy art, culture, and heritage in Brazil.

Afro-Brazilian dances are diverse expressions within the corporeal patrimony of Brazil. These varied cultural forms are practiced, conserved, and disseminated by a community made up of groups or individuals who identify with Afro-Brazilian heritage and wish to affirm their identity and be recognized as full Brazilian citizens who transmit knowledge through their cultural expressions. These expressions include religious rituals such as Candomblé, Umbanda, and Xangô; entertaining and ritualistic game/dances such as capoeira and maculelê; choreographies found in afoxés, maracatus, congadas, and bumba meu boi celebrations; and in popular, street or community forms like frevo or jongo. In addition, there are new, contemporary formats that are Afro-Brazilian recreations and innovations by individuals and dance/music companies and schools, as in the cases of Balé de Cultura Negra do Recife – Bacnaré (Pernambuco), Balé Folclórico da Bahia (Bahia), and Cia Étnica (Rio de Janeiro).

To understand the complexity that Afro-Brazilian dances involve, I raise the following questions:

- What did African legacy dances represent for enslaved Africans?

- How are danced cultural expressions perceived in historical and contemporary discourses?

- What role do Afro-Brazilian dances play in the construction of racial identity today?

To address these questions, I have consulted studies on the relationship between education and black identity (Siquiera 2006; Kabengelê 1986); studies on black activism (Junior and Melgaço 2007); documentation by historians (Reis 2002; Mattos 2008); and research completed by dance scholars (see Tiérou 2001; Nóbrega Oliveira 2007; Martins 2008; Videira 2009; Suárez 2013 among others). I also draw from my own experiences as an Afro-Brazilian dance teacher, choreographer, and researcher who actively participates in the socio-political Black Movement of Bahia.

The Meaning of Dance for Enslaved Africans

Prior to European occupation, ancient Indigenous peoples dominated the territory now known as Brazil with their ways of life, forms of social organization, and diverse knowledge systems. European colonization greatly reduced Indigenous populations in South America, imposed a new cultural model, and transformed values within the new territories. Despite the genocide, many ethnic groups survived and are still present in the twenty-first century. According to theater and dance researcher Clélia Neri Côrtes (1996), there are 240 Indigenous groups living in Brazil today. Referring to the European “civilizing” model, Côrtes points out that Jesuit pedagogy, which favored writing and reading, lasted until 1758 when the Jesuits were expelled from Brazil by the Marquis of Pombal. Their model emphasized a lack of dialogue among the civilizations that formed early Brazilian society: Amerindian, European, and African. Côrtes adds that the Jesuit model of education was characterized by domination of “the other” and the interdiction of the body (see Freire 2014).1

In 1539, in a letter to King John III of Portugal, there is a request for the importation of Africans from the coast of Guinea, for a fee. Although colonizers often confused African ethnic groups, called “nations” in the African Diaspora,2 with the ports from which Africans had departed the continent (such as Cape Verde, Mina Coast, Ajudá, and others), enslaved Africans or blacks in Brazil came from all over West and Central Africa, which included regions such as Minas, Ardras, Daomés, Sudaneses, Cambindas, Angolanos, Congos, etc. With them came their dances, songs, and customs. The continuity and recreation of their dance practices and the transformations that they underwent during the enslavement, migration, and colonization processes became the foundation of what we now call danças afro (African dances); they are historical memories preserved in dance performance.

Researching records in Pernambuco from 1674 of the Irmandade de Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Homens Pretos da Paróquia de Santo Antônio (the Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men of St. Anthony Parish), historian Leonardo Silva (1988: 15) found documents that refer to the coronation of Angolan, as well as Brazilian-born blacks (crioulos) as kings and queens. These data suggest that the coronation proceedings subsequently gave rise to maracatu and similar parade-type processions with dancing, singing, and playing of musical instruments. L. Silva observes that the first known cortege of dignitaries from the Kingdom of Congo to Brazil was documented by Gaspar Barleaus in 1643, who described a delegation that visited Recife to meet with the Dutch Count João Maurício de Nassau3 and address issues involving the King of Congo and Count of Sonho. Count Maurício de Nassau describes the occasion: “[…] we saw their original dances, flips, fearsome sword flourishes, flickering eyes simulating anger at the enemy. We also saw the scene in which they represented their king sitting on the throne and witnessing the majesty in dogged silence” (1988: 17).

Bahia

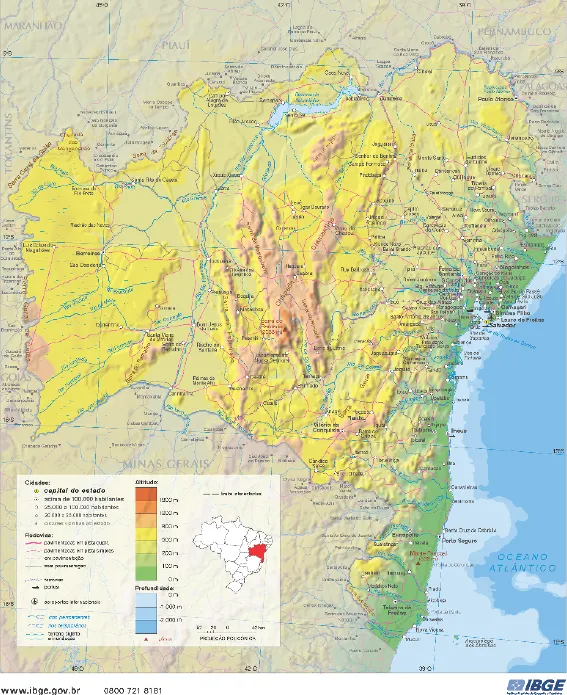

Figure 2: Map of the State of Bahia.

Additionally, I conducted research for IPHAN (the Historic and Artistic Institute), a dossier on samba de roda4 within the interior of Bahia, and found that “there is no scarcity of documentation of black drumming and other musical and choreographic sessions” (Conrado 2008: 32). My discussion refers to studies by historian João José Reis that mention an 1808 document concerning a massive festival that took place in the Santo Amaro region, with African and black or African-descendent music and dancing and a significant number of whites, all with the consent of local slave owners and to the annoyance of provincial police authorities (2002: 105). Within the context and dynamics of a society dominated by enslavement practices, transformations took place as a result of both internal and external pressures, affecting slave trafficking and the institution of slavery itself. The Free Womb Law (Lei do Ventre Livre, 18715) and the Sexagenarian Law (Lei dos Sexagenários, 1881) were only able to legitimate and confront on their own terms what was left of [the] Masters’ dominion over their slaves, putting on the horizon the end of slavery itself” (Mattos 2008: 152). Such pressures forced the Portuguese Crown to take an action that could no longer be postponed, and Imperial Law No. 3353, known as the Golden Law (Lei Áurea), was signed by regent Dona Isabel on behalf of Emperor D. Pedro II, proclaiming the abolition of slavery on May 13, 1888.

Of course, abolition was cause for great celebration by the formerly enslaved population. Many of these celebrations remain etched in popular memory to this day – in the form of dances, poems, and songs. However, the historical literature on slavery in Brazil reveals that celebration was not the only meaning given to such festivities. For the colonial population, the festivities also signified resistance, just like running away, murder, and suicide constituted extreme individual forms of African and African-descendent struggles against colonial slavery (Mattos 2008: 168).

In my later fieldwork, I have observed other examples of historical memories that are preserved through dance performance. One is the annual performance of a dance called parafuso or the “dance of the screws”. It is usually presented at the Laranjeiras Cultural Festival (Festival Cultural de Laranjeiras) during the period of Three Kings’ Day (Folia de Reis) in January.6 The dance of the screws was created just for men, who move to the rhythm of the music, gyrating tirelessly, wearing white dresses, shoes, hats, and white makeup on their faces. Their “dresses” are actually long full petticoats. Members of the group explain that during the time of slavery and in the middle of the night, Africans would steal young ladies’ petticoats from the clotheslines of the master’s houses. They would cover their whole bodies with the petticoats in attempts to simulate ghosts, awaken and frighten the colonists, and then try to escape through the woods. When the Golden Law was signed, groups of African-descendent men dressed in petticoats came out frolicking and dancing, thereby revealing the “secret” of the hauntings. This is still preserved in the oral memory of dance groups that perform the parafuso.

In attempts to confirm the story, I found a citation in a 1985 publication that briefly describes the parafuso dance: “Black slaves, their faces covered with Tabatinga (paint used to whitewash houses), wearing white petticoats of Irish linen and lace decorated with toothpick folds […]” and “[…] humming and making a huge fuss, in a twisting back-and-forth dance, they took to the streets to make fun of their masters, who had been defeated on May 13” (Fundação Estadual de Cultura 1985: 13).7

There are other examples of African heritage in Brazilian dance culture that refer to the memory of the struggle and the quest for freedom from bondage, which simultaneously reveal the complexities the dances involve. I highlight two significant corporeal expressions: maracatu dance practices and the nego fugido (black runaway) dance variations. Maracatu is an artistic or cultural event from the state of Pernambuco that involves a large number of groups; nego fugido is a smaller event that takes place in the interior of the state of Bahia. I consider both as dance expressions that have moved across historical time to the present, retaining tremendous vitality.

Memory and History through the Lens of Maracatu

Maracatu is most known as a traditional dance in the form of an African royal procession, practiced in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. “Maracatu street presentations display much grandeur with ornately costumed characters, such as kings, queens, vassals, ambassadors, spearmen, baianas, cortesans, and ladies of the imperial palace. The protagonists of maracatus are representations of enslaved Africans and their Brazilian descendants, who also worshiped the Africanized forms of [the Catholic] religion” (Conrado 2013: 2). Maracatus naçãoes or maracatu nations, so named by the communities from which they come, are forms of identity affirmation and ethnic belonging, signaling the organization of black resistance. There are many maracatu variations; for example, maracatu nação Estrela Brilhante, nação Porto Rico, nação Cambinda Velha, nação de Luanda, and nação Elefante.

Dance education scholar Margarete Conrado draws attention to the meaning of maracatu as a dance that mixes festive and warlike characteristics, calling it a “beautiful war” (2013: 14). The prefix “marã,” in the language of the Tupi-Guarani, means “war, confusion, disorder, revolution.” “Catu,” also in Tupi-Guarani, means “good, beautiful.” Other authors attribute the origin of the dance or event name to the musical instrument called maracá, which is an indigenous rattle. Silva, in his study of the institution of the King of the Congo and its presence in maracatus, traces the dance to the beginning of Brazilian enslavement practices in 1530, in the captaincy of São Vicente. I consider it a processional dance that represents the coronation celebrations of Kings of Congo, organized by the Irmandade do Rosario (Brotherhood of the Rosary) in the colonial period and linked to Catholic festivals of the Three Kings.

In his doctoral research on maracatu rural (rural maracatu) or de baque solto (loose-beat maracatu), José Antonio Leão explains that the culture of maracatu unfolds in several ways (2011: 36–37). The name of this form refers to the loose playing of drumsticks on the snare drum and it differs from the maracatu nação or de baque virado (reverse-beat maracatu) because of its particular musical sound, but also because unlike the maracatus naçaoes versions, maracatu rural includes the fusion of Indigenous and African representation. Maracatu performances incorporate an orchestra consisting of bass drum, snare drum, cuica gonguê, and ganzá,8 as well as unique stock characters, such as the caboclos of the sword,9 who embody the local customs and everyday life of the region known as Nazaré da Mata. Thus, regional residents participate in the process of preservation, reconstruction, and dissemination of their culture; however, Leão attributes the historical origin of the maracatu rural to the mixture of Indigenous, European, and African cultures around the end of the nineteenth century (2011: 37). This fusion is found within many cultural practices, such as pastoril, bumba meu boi, cavalo-marinho, caboclinho, folia de reis, etc.

Maracatu would come to be associated with the most widely used term, “nação” or “nation,” which (again) marks the identity and ongoing presence of African peoples everywhere it was performed. Repression of “all things African” led blacks to seek a time and space where they could come together, recall and affirm th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Bahian Dance in Action

- Part II: Memory, Resistance, and Survival through Dance Education

- Part III: Reflections: Paths of Courage and Connections

- Part IV: Defying Erasure through Dance

- Notes on Contributors

- Index