![]()

PART 1

FILM AND THE END

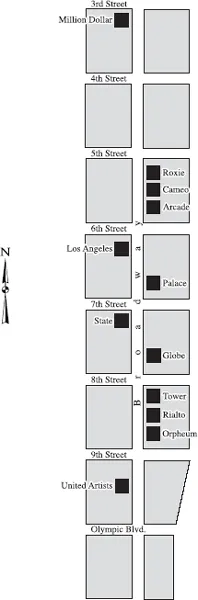

Los Angeles Broadway 1

Film’s end begins with a glorious scar on the face of the city. Once the end of film has been located, the eye can travel in any direction, backwards in time, forwards in time, or more profoundly into a moment of immediacy, and into the transformative space and corporeality of filmic ruination. Film’s end is a matter for the human eye, for memory, and oblivion.

The Broadway avenue of downtown Los Angeles holds the greatest concentration worldwide of abandoned, but intact, cinemas, whose histories encompass almost the entirety of the existence of film, together with its obsessions, caprices and mutations. That procession of once-lavish and luxurious cinemas, the zenith of technological innovation in their respective moments of construction, along the Broadway avenue, forms a geographically linear graveyard in which to experience film’s end, running directly north to south. The parallel westerly avenues carry innumerable corporate image-screens (the digitally animated advertising surfaces that became pervasive in cities worldwide in the early 2000s, fluctuating in scale from the size of an entire building’s facade to that of a minuscule display screen) and highrise banking towers, while the adjacent easterly avenues contain archaic, century-old skid-row hotels and now-illegible, tea-painted hoardings for long-gone companies, inscribed directly onto the upper storeys of the buildings’ walls.

Filmic history can now only exist in fragments, since its amalgamation with the digital has irreparably scrambled its resolution, but also because film itself was never a medium to be incorporated and defused within the linear, the historical, the categorical, and always wielded an integral capacity for aberrance, for the arbitrary and for the shattering of time. Even in their geographical existence, the cinemas contained in the linear north–south avenue of Broadway possess contradictory histories, multiple origins and ends, as well as disparate architectures, facades and interiors. In most cities worldwide, a collection of grandiose cinemas such as those of Broadway, once obsolete and emptied out, would have been demolished, as happened in many cities, such as San Francisco, Tokyo and London, so that such cinemas’ presence, and its deep embedding in the lives and visions of those cities’ populations, would have to be conjured or hallucinated back into existence, or substantiated with photographic and memory-based evidence, in order for that once-seminal aura of cinema to even subsist in the contemporary moment. By contrast, in Los Angeles’s Broadway – in large part through the power of indifference and oblivion itself, exercised in what, for decades, was a near-forgotten and neglected zone of the city – the abandoned cinemas perversely survived, as they did in the avenues of other cities, such as Lisbon and Riga, thereby tangibly embodying, in their contrary dereliction and endurance, the living end of film.

From the northernmost point of Los Angeles’s Broadway, the twelve cinemas extend down the avenue as an astonishing litany of names emblazoned on dilapidated but still-prominent marquees and signs: the Million Dollar Theater, the Roxie, the Cameo, the Arcade, the Los Angeles Theater, the Palace, the State, the Globe, the Tower, the Rialto, the Orpheum and the United Artists Theater. Several of them were originally named after the cinema entrepreneurs who built them (Alexander Pantages, William H. Clune), and acquired their later names once those entrepreneurs had vanished into obscurity or bankruptcy. Most of the cinemas are constellated in small groups, alongside or opposite one another, with the Million Dollar Theater and the United Artists Theater, at the extreme ends of the avenue, stranded at a block or two’s distance from the others. The cinemas of Broadway were all constructed between 1910 and 1931, with the first and last cinemas (the Cameo and the Roxie) positioned directly alongside one another. During those two decades of the cinemas’ pre-eminence, Los Angeles’s film premieres and first runs of major films often took place in Broadway, and the night-time avenues became saturated with crowds awaiting the arrival of searchlight-illuminated film stars. That interval of two decades, its origin only fifteen years on from the first ever public film screenings, in 1895, and its ending seventy years or so in advance of the engulfing onset of the digital era, around the year 2000, is a moment stranded within competing film histories; those histories left the Broadway cinemas marooned within the city’s space, once the onrush of Los Angeles’s film industry had transplanted its axis westwards, towards Hollywood, at the beginning of the 1930s (extending a trajectory that had already propelled that axis from a transitory origin two avenues eastwards, in Main Street, site of Los Angeles’s ramshackle and ephemeral nickelodeons). As a result, the cinemas of Broadway remained within their own cracked fragment of history, and their own scorched-earth urban terrain.

Los Angeles Theater foyer (fragment).

The facades and interiors of the Broadway cinemas were designed to transmit infinite luxury and maximal expense to the eyes of their audiences; that excessive expense could even serve to name the cinemas, as with the avenue’s northernmost cinema, the Million Dollar Theater. In many cases, shopping arcades and office complexes were incorporated into the architectural design, either surrounding the cinema’s auditorium or else extending several storeys above it. The cinemas’ exterior design relentlessly propelled their audience’s eyes into the interiors, beginning with the vividly coloured solar mosaics embedded into the public sidewalks in front of the foyers. The facades, often constructed with premium-quality stone imported from Italian quarries, and intricately carved and decorated with figures drawn from European or Mayan mythologies, both exclaimed the titles of current films on colossal marquees and hoardings, and intimated that the film-going experience was to be a lavish, cultured one. Each foyer accentuated that extravagance, with opulent decoration replicating Versailles palace interiors or Gothic infernos, and led to marbled restrooms, restaurants, walnutpanelled smoking-lounges and sound-proofed areas in which to exile wailing children. The projection-box contained the latest image technology, and the entire building demonstrated technological innovations, including systems to transmit the film image onto miniaturized screens for the socializing audience seated in the lounge areas. Inside the auditorium itself, often able to seat several thousand spectators in multiple tiers, balconies and side-boxes, the audience first saw the spectacular fire curtain, emblazoned with sunbursts or planetary constellations, before the vast screen was revealed and the film began.

The cinemas had been constructed so that their own eventual disintegration and ruination would form an equally compelling ocular and sensorial spectacle to their originating moment of glory. In some cases, the moments of their completion and redundancy were near simultaneous; the Los Angeles Theater, constructed as the venue for the premiere of Chaplin’s City Lights in January 1931 (Chaplin arrived in Broadway with Albert Einstein, in front of Depression-era crowds forming hostile bread-queues rather than an entranced audience), had gone bankrupt by the end of the same year. New cinemas, such as the Chinese Theater and the El Capitan Theater, had already been built on Hollywood Boulevard, and now supplanted those on Broadway as the film industry’s preferred venues. Each of the twelve Broadway cinemas passed through the following five decades in different ways, with some cinemas packed beyond capacity, 24 hours a day, during the war years of 1941–5, for cut-price screenings of B-movies and newsreels. The avenue’s department stores, which had formed another point of attraction for its cinemas’ audiences, declined over the postwar decades, leaving empty buildings, and a huge influx of Mexican and El Salvadorian street-traders led to many cinemas specializing in South American films, before spiralling downwards into an array of martial arts and exploitation genres. By the late 1970s and into the ’80s, Broadway had become a forbidding part of the city at night, with few people remaining in the streets after dark other than the mad, desperate and homeless; at times, otherwise-homeless people literally lived in the never-closing cinemas. All-night screenings for riotous audiences of cult-film die-hards left the cinemas’ original screens indented by thrown missiles, torn and stained; several cinemas supplemented their film-screenings with one-off performances by the era’s punk bands. One cinema, the Rialto, was closed down since its construction no longer met earthquake regulations, but in most cases, the cinemas ended in pornography, with depleted audiences transfixed by images of pornography stars spraying semen on the already stained screens. By the early 1990s, all had ceased showing films, taking on their new status as abandoned cinemas.

Million DollarTheater tower (fragment).

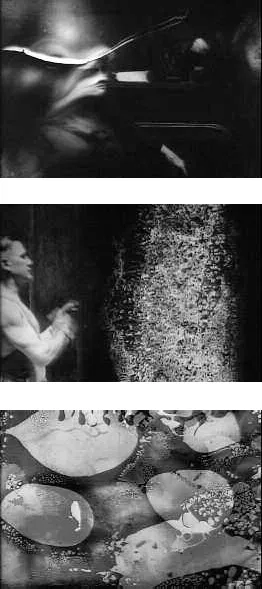

Decasia, 2002.

The transformation of the Broadway cinemas by their abandonment reveals how those ghost-spaces retain the aura of film and accentuate it into a vital matter of memory and destruction, and how those spaces enable the prising-apart of filmic obsession, to show both its seminal power and the power of its disintegration. The post-humous mutation of those cinemas since their closures – into cultist churches, nightclubs, sex venues, experimental art spaces, shop-storerooms for plasma televisions and digital artefacts, or simply into petrified spaces of accumulated ruination – also illuminates how film, with its ongoing, hybrid mutations, even after its ostensible ‘death’, remains the pivotal medium for human experience and for its new forms of vision.

Approaching Broadway from the north, the first element to be seen of those cinemas’ traces, rising above the adjacent buildings, is the summit of the office tower built above the Million Dollar Theater, imprinted with the date of its construction, 1918 – and once occupied by William Mulholland, the legendary bringer of water via aqueducts to the newly developing city of Los Angeles, and a figure demonized as an incestuous and immoral criminal by Roman Polanski, as his fictional character Noah Cross, in the 1974 film Chinatown, whose narrative castigates the very origin and means of creation of the film-megalopolis of Los Angeles.

Anatomizing Cinema’s Death

Film has had so many ends, so many deaths, that an objective observer of the medium (an omniscient and dispassionate onlooker from another time, like those observing the visions of the human species in Chris Marker’s film La Jetée) might conclude that its pioneers of the 1880s and ’90s had created it purely in order to have the perverse pleasure of killing it, or of watching as its materials deteriorated, and its spaces became abandoned. One of the great advocates of the death of cinema, the film archivist Paulo Cherchi Usai, wrote of how the digital era formed an antithetical and non-aligned presence to that of film, and that the vital work of the film archivist was now to observe and record the intricate processes of decay which manifested film’s disintegration, as the nitro-cellulose base of the material used in cinema’s early decades gradually returned to its constituent elements: nitric acid, camphor and cotton: ‘The ultimate goal of film history is an account of its own disappearance, or its transformation into another entity.’1 The digital theorist Lev Manovich has observed a comparable process of decay in the digital image data that has superseded film, noting that ‘while in theory, computer technology entails the flawless replication of data, its actual use in contemporary society is characterised by loss of data, degradation, and noise.’2 Usai also makes this parallel between the processes of decay which unite two otherwise irreconcilable media, the filmic and the digital: ‘As soon as it is deposited on a matrix, the digital image is subject to a similar destiny; its causes may be different, but the effects are the same.’3 The digital image is as precarious and fragile an entity as that of film, additionally exposed (unlike film) to the permanent possibility of a technological meltdown or digital crash engendered by social instability or human caprice; but the digital image’s death remains a new and unknown one, while film possesses a long history of ends.

Decasia, 2002.

The fascination which abandoned, ruined and expiring cinemas exert upon filmmakers worldwide is evident in numerous films located in such spaces, such as Tsai Ming-Liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), Wim Wenders’s Lisbon Story (1994) and Theo Angelopoulos’s The Beekeeper (1986); such films often explore and foreground the space of the decrepit cinema’s projection-box as the pre-eminent, revelatory site of film’s abandonment. That fascination with terminal cinematic space forms a variant of a compelling filmic preoccupation with envisaging and probing its own decay and erasure. And like the work of dissection performed by an anatomist, the close observer of film’s end is working on corporeal as well as visual materials. The filmmaker Bill Morrison made an explicit alliance between the decay of film and the decay of the human body in his 2002 film Decasia, whose production consisted of literally filming the disintegration of film, in the form of sequences from documentary and fiction films which had deteriorated in the archives in which they were stored, so that the human bodies held in those sequences now distort, deliquesce, vanish, suffer total erasure, exude ghostly ectoplasm, before abruptly resuscitating themselves, apparently miraculously, whenever the process of decay has affected only a limited sequence of film-footage. Morrison notes that: ‘Like the film, our bodies will eventually be reduced to what essentially forms us. What they contain is who we are: our thoughts, dreams and memories.’4 The end of film, then, may possess an aberrant narrative twist, entailing a liberatory unleashing, in which an interrogative viewing of the process of decay or abandonment undergone by film’s images (reels confined to decay in film-cans), or film’s spaces (cinemas that have been abandoned), finally releases those incendiary charges of memory and dreaming that Morrison observes, now in a sensorial and ocular form intensified by their confinement within the space and time of filmic death, so that they emerge mutated and transformed, with new impacts for the human eye.

Announcers of the death of film have often pinpointed particular moments for that terminal event: moments often determined by preoccupations with time or technology. Purists who prefer film as silent (or as combined only with music) have vilified the coming of sound, and especially of a synchronized vocal dimension, to film’s industries at the end of the 1920s, as marking that falling-away point, and with it the closure of a period of sustained experimentation with the film image, that had already been taken to a state of inventive extremity in F. W. Murnau’s film Sunrise (1927), in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1928) or in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), and that could have been taken further, if film had maintained its silence. Other moments of perceived film-death constellate the subsequent history of cinema, gathering momentum towards the end of the twentieth century. For filmmakers who began to see the potential for digital image-making as a creative strategy, the early 1990s marked a moment when it appeared that film could now be technologically surpassed by an exciting new medium which – at that moment, before the engulfing digitization of everyday life that had taken hold by the end of that same decade – would constitute a natural transition onwards from the filmic medium; filmmakers such as Peter Greenaway and Wim Wenders presented their films of that era, Prospero’s Books (1991) and Until the End of the World (1991), as embodying the way in which the digital image could carry every visual texture and resonance that film had, but in an infinitely enhanced and expansive way. A further moment of film’s announced end came in 1995–6, at the time of the centenary of the first film screenings for a paying audience, held by the German film-pioneers Max and Emil Skladanowsky at the Wintergarten Ballroom in Berlin on 1 November 1895, and the subsequent public screenings by the French film pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière in Paris. That variant on the death of film assumed that the medium had possessed a finite lifespan: one hundred years, to the second, as though the first moment of projection at the Wintergarten Ballroom marked its origin, and the winding-down of the film-reels’ revolutions at a screening a century later marked its demise. The film theorist Laura Mulvey noted the engrained preoccupation with death in film, and the speed or stilling of film-projection that is integral to the mediation of filmic death, in her book Death 24x a Second. She proposed that the years following 2000 also marked another of film’s deaths, since the momentum of the digital era’s ascendancy across the 1990s appeared increasingly intent on obliterating film entirely, and also because the years following film’s centenary had seen the disappearances of seminal film icons such as Marlon Brando: ‘As time passes, the ghosts crowd around the cinema as its own life lies in question and the years around the centenary saw the death of the last great Hollywood stars. ’5 Film now became so...