![]()

1 Spatiality

In the remote past, people buried the dead in the open field under thick brushwood, without constructing tumuli or planting trees. The period of mourning was also not regulated. The later sages then replaced this ancient custom with inner and outer coffins.

The Book of Changes1

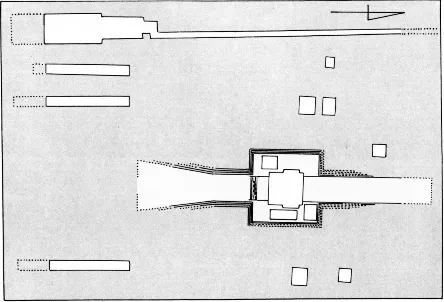

Any tomb is created first as a vacuum – it starts out as a pit dug in the earth, rocks or wood piled up to make a hole, or a cave carved in a hillside. The construction of a permanent architectonic space for the dead was a later practice, however. Before then, the vacuum in a grave was typically filled with dirt or rubble around the corpse. Zhao Zi of the second century CE thus considered the invention of the coffin the single most important event in the history of tombs; all later developments of the burial structure only elaborated upon the notion and form of the coffin, which, in a rudimentary but highly conceptual manner, first materialized and stabilized a special space for the dead.2 Zhao attributed the invention of the coffin to the Yellow Emperor, a legendary ruler in antiquity who is also described in Han texts as the inventor of ritual and state-craft.3 Following the Yellow Emperor’s steps, according to Zhao, the royal house of the Western Zhou multiplied the layers of coffins and embellished them with surface decoration, and the powerful warlords of the Eastern Zhou constructed large, luxurious mausoleums for themselves, ‘squandering a handsome sum from state coffers in the realm of the Three Springs [i.e., the Yellow Springs].’4 Modern archaeology has basically confirmed the historical development outlined by Zhao Zi. Based on scientific excavations, we now know that stone and pottery coffins had appeared in China by at least the mid-Neolithic period, about 6,000 years ago (illus. 6),5 that burial structures in elite Western Zhou graves indeed bore ornate images,6 and that large mausoleums became fashionable among the Eastern Zhou warlords during the fourth and third centuries BCE (illus. 7).7

One of these Eastern Zhou warlords finally unified China and bestowed upon himself the imperial title Shi Huang Di – the First Sovereign Emperor of a (supposedly) everlasting dynasty. Not coincidentally, his tomb, called the Lishan Mausoleum, reached a new, astonishing level in both scale and conception. We will return to this tomb many times in this volume. For the moment, it is important to note that the First Emperor’s undertaking also inspired the first description of an underground grave chamber in China. (The earlier quotations from The Book of Rites and Mr Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals are not a description of an actual burial, but only prescribe certain general principles of tomb construction.) This famous passage comes from Shi ji, or Historical Records, by Sima Qian (c. 145–c. 90 BCE). In his biography of the First Emperor, this Grand Historian of the Western Han (who wrote nearly a century after the First Emperor’s death) recalls how the emperor assembled 700,000 workers from all over the country to build his tomb:

6 Pottery coffin for a child, Yangshao culture.

Neolithic, c. 3500 BCE. Excavated in 1978 at Yancun, Henan. | |

They dug through the Three Springs, stopped their flow, and built the burial chamber there. They carried in [models of?] palaces, pavilions, and the hundred officials, and strange objects and valuables to fill up the tomb. . . . With mercury they made the myriad rivers and the ocean with a mechanism that made them flow about. Above were all the heavens and below all the earth.8

This amazing space was not to be entered by mortal men, for the emperor ordered crossbows and arrows set up there, rigged so that they would shoot anyone attempting to break in. Even visions and memories of the underground site had to be erased: all the builders and craftsmen who had worked in the tomb were locked inside when ‘the inner gate was closed off and the outer gate lowered’, so the secret they knew would be forever kept within the tomb.9

7 Plan of the Mausoleum of King Cuo of the Zhongshan kingdom at Ping-shan, Hebei. Warring States Period, 4th century BCE. | |

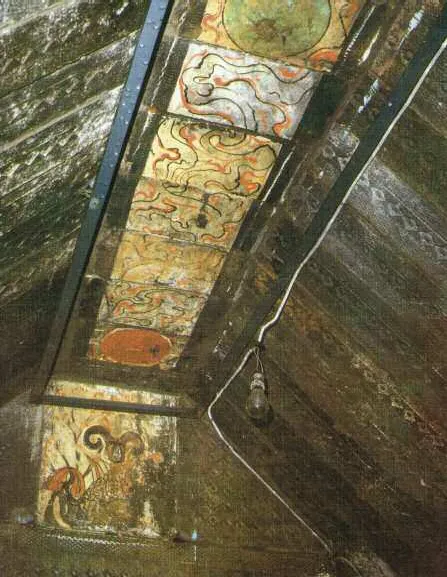

The First Emperor’s burial chamber is not yet excavated and we still cannot verify Sima Qian’s report.10 In fact, no excavated pre-Han tomb is decorated with images of ‘heaven above and those of earth below’. The earliest known examples painted with such images date from the first century BCE, over a century after the First Emperor’s death but close to Sima Qian’s own lifetime (illus. 8).11 An inquisitive reader of Shi ji may also question how Sima Qian knew the tomb’s interior if those who had seen it were all murdered and no one was allowed to enter the space afterwards. Of course, one can always argue that somehow the tomb’s secret leaked out despite all the precautions taken by the emperor and his heir (who was instrumental in locking up the workers inside the tomb). But one can also make an equally strong argument that the mystery surrounding this unseen space would stimulate fantasy, and that later writers and artists (not just Sima Qian but also modern historians, novelists and especially film directors) would give free reign to their imagination, trying to envision this most amazing tomb created in ancient China.

| 8 Painted ceiling of Shaogou Tomb 61 at Luoyang, Henan. Late Western Han, 1st century BCE. |

Before the First Emperor’s grave is eventually opened, it would be unwise to determine which of these two scenarios might have given rise to Sima Qian’s report. What we can say with confidence is that his description combines two basic models of tomb construction and decoration, both responding to the desire to transform a tomb’s interior into a symbolic, illusionary space. In the first model, a tomb is arranged to simulate a microcosm of the universe, with its essential components – heaven and earth being the most important – represented in different positions according to the prevailing cosmology. In the second model, a tomb provides the deceased with a posthumous home by transporting his worldly possessions – in the First Emperor’s case, his palaces, subjects and valuables – to an underground space. These two models are not antithetical, and can exist either independently or in various composite forms. They can be integrated because a replicated living environment can be presented as an intrinsic feature of a model universe, whereas a model universe can be conceptualized as the ‘cosmic dwelling’ of the departed soul. But more fundamentally, these two spaces can supplement each other because both are constructed for the dead, who alone fulfil the ritual and symbolic significance of these spaces by inhabiting them.

Thus even though we cannot take Sima Qian’s description for the actual burial chamber of the First Emperor, we learn from his words some basic notions and impulses in constructing, decorating and furnishing a tomb in ancient China. Taking the passage as its starting point, this chapter explores various manifestations of these notions and impulses. If the invention of the coffin forged an insulated architectonic space for the dead, the next crucial development was to elaborate this space into an underground household or microcosm. In the history of Chinese tombs, this development was achieved through replacing a casket grave with a chamber grave.

From Casket Grave to Chamber Grave

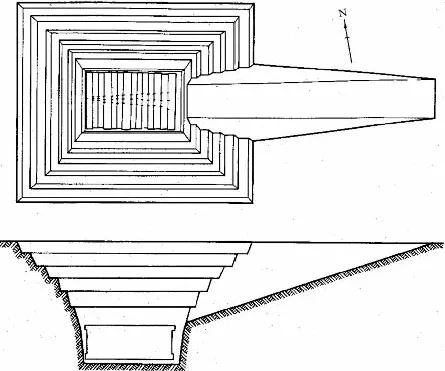

A ‘casket grave’ (guo mu) is a tomb with a box-like timber structure buried at the bottom of a vertical shaft (illus. 9). This burial type is therefore also known as a ‘vertical-pit grave’ (shuxue mu).12 The traditional Chinese term for the timber structure is guo, an ‘outer coffin’ that encloses one or more ‘inner coffins’ which are called guan (illus. 10). Although eventually assembled into a nested set of caskets, guan and guo are distinguished by a number of crucial features. During the Eastern Zhou and Han, for example, a guan was made before the funeral and even long before a person died; a guo was constructed inside the grave pit right before the entombment. A guan was a single rectangular container with a flat or curved lid; a guo often consisted of multiple compartments to store coffins and grave goods. A guan was frequently painted with elaborate patterns (see illus. 178); most guo bore little embellishment. A guan was displayed during the funerary ceremony before the burial; a guo served no role in such exhibition. On the day of the burial, after workers built the guo inside the grave pit, they lowered the guan and burial goods into it, and then sealed the guo with a heavy lid. The pit was then filled with dirt; and a mound was erected on top to mark the location.13 Most important for a casket grave, the timber structure inside it was intended as a self-contained unit, without a side-entrance connecting its interior with the outside. If there was a ramp attached to the vertical pit, it only reached the upper edge of the casket to facilitate the entombment (see illus. 9).

| 9 Cross-section and plan of Wangshan Tomb 1 at Jiangling, Hubei. Warring States Period, 4th century BCE. |

Scholars have traced the origin of the casket grave to the single-coffin tombs of Yangshao culture, a large cultural complex which flourished in the mid- and upper Yellow River regions from the fifth to the third millennia BCE.14 A timber frame was later constructed around the coffin in some elite tombs belonging to Dawenkou and Liangzhu cultures, two east coastal cultures dating from the fourth and third millennium BCE (illus. 11).15 Mature casket graves finally appeared in the Longshan culture in the Shandong Peninsula during the third millennium BCE. In Tomb 1 at Xizhufeng near Linqu, for example, two guo-structures made of wooden planks not only enclosed a coffin but also contained boxes of grave furn...