![]()

PART I

Romanticizing the World

‘Die Welt muss romantisiert werden. So findet man

uden ursprünglichen Sinn wieder.’

The world must become romanticized. That way one finds

again the original meaning.

Novalis

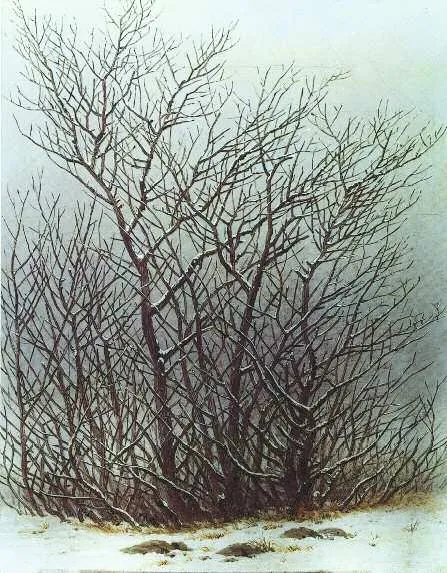

1 Trees and Bushes in the Snow, 1828. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden.

![]()

1

From the Dresden Heath

You are placed before a thicket in winter (illus. 1). The thicket, a cluster of bare alders, rises from the snow to fill your gaze: a mesh of grey-brown lines traced sometimes with white. The alder.’ forked twigs and branches, tapering to sharp points, compose loose patterns against the dull sky. Here and there appear regular networks, the products of branches evenly spaced, overlapped and viewed from one spot before the thicket. Just above the ground, where the thicket is densest, you see branches dissolving into an abstract play of criss-crossed lines. Only rarely, however, has the artist simply x-ed his canvas with thin brown lines, heedless of the logic of each individual plant. In the variously pointing twigs near the canvas’s edge, in the curved and unpredictable growth of larger, moss-covered stems which pass over and within the network, the artist recuperates – becomes a scholar of – the singularity of this thicket. The random signature of each specific twig as it forks out at its own angle, and in its own shape and thickness (despite whatever law commands its ordered growth), underwrites the particularity of the whole. It testifies that the network was and is this way, and no other way, and that you, therefore, are placed here, rather than elsewhere, before this thicket in winter.

Somehow the painting places you. Somehow it singles you out to stand before a thicket, just as it singles out each individual branch of that thicket and displays its particularity against the dull sky, as if the singular itself were contingent upon the placement of your eye. Once installed, you seek confirmation of your arrival, some motivative sign or plot that will explain why you are here. The thicket, though, is unremarkable. Neither is it itself a superior specimen of a thicket, nor does it shape a space before itself which could be a setting for other, more remarkable, presences. The alders stand lifeless, their dull brown branches composed in random, broken configurations. The snow that highlights and surrounds the thicket is itself sullied variously by withered crab grass, clods of grey soil and dry leaves trapped since autumn among the alder stems. You do not stand before a ‘landscap.’, since the thicket blocks any wider prospect of its setting; nor do the snow and alders, pushed up against the picture plane, quite constitute the monumentality of a ‘scene’, for they provide no habitat for an event.

What alone welcomes you, what corresponds to your attention, is the thicket’s very placement in a picture. The visual field centres itself around the alders, framing them off as systematically as any random mesh of branches can be framed. The few twigs that pass out of the picture (at the left and beside the patch of blue sky) seem controlled by fine-tuned coincidences of picture edge and outer twig elsewhere. And, above and below, the open sky and snow-covered earth preserve a certain margin around the thicket. That is, although you are placed before nothing that should command your attention, this void, pictured, seems already to imply your gaze. The framed and centred thicket appears to you, if nothing else, as something viewed. You might believe that it is yours whose sight you see of a thicket in the snow. You might even suppose, in a space as lifeless and alone as this, that all the order is the order of your gaze, the patterns of the branches ones that you have arranged.

This painting, however, will not be familiarized. Towards you the thicket borders on the solid, mundane ground of clods, dead grass and snow. Further into space, however, in the thick of the alders, the ground drops off indeterminately. You could presume that the foreground snow simply gives way to a gentle sloping of the land, or that the thicket is rooted in a sunken patch of earth. Yet your placement forbids certainty on this matter of ground. At their bases, the alders stand silhouetted against a narrow, horizontal stripe of purplish grey, delimited below by the snowy foreground’s curved edge, and above by a band of lighter grey. This stripe may invoke the thicket’s spatial extent, yet it neither measures, nor limits itself to, that space. Indeed its blurred boundaries, neutral colour and nebulous shape render space radically indefinite, causing the alders to appear as presences conjured up from a bottomless deep. The thicket’s placement at the very centre of the canvas, moreover, its seeming coincidence with the order of your gaze, only intensifies the caesura between the mundane and particularized foreground in which you exist and an entirely indeterminate and potentially infinite background. For by insisting that the edges of the canvas appear as the limits of the thicket, the painting confounds any ordered progression of vision into depth, any contextualization of the thicket within a stable and continuous ‘terrain’. The thicket thus rises up before you abruptly, as pure foreground, like a net woven over an abyss.

You survey the painting for the trace of a horizon. You search for something more than just a shallow foreground spread out immediately against the sky. Less than a third of the way up the canvas, you are given a sign: a subtle shift in areas of grey, in painted planes of grey, that meet along a blurred horizontal line about where the horizon might be. Below, the lighter plane is a band mirroring the foreground strip of snow in size and shape. It can read either as a hazy winter landscape stretching indefinitely into the distance, or as merely a division within blankets of fog or clouds. This line, hardly a line, is too insubstantial to confirm for you the meeting of earth and sky, yet you balance your vision against this even change of hue from pale to darker grey. Call this the world in which the thicket stands. You bear down further on the painting. You examine its surface, where those planes of grey meet along a horizontal. No change of substance is registered here, only the universal blank of pigments evenly applied. You bear down, too, upon the thicket, upon that overpainted network of lines that control the scene’s particularity. This is a thicket fashioned of thinnest paint, a mere glaze of greyish brown laid down translucent, like the fog that is its ground, over grey. Here you discover the thicket’s only stable scale (for who is to say whether the alders are trees or shrubs?): a thing no larger than the painted likeness it is, a miniature on a canvas 31 x 25 cm in size. An unremarkable object decorating the unremarkable. You have surveyed the thicket and found it groundless – alders on a void, themselves a void. You turn at last to interpret what you see.

The scene of a thicket in the snow may stand devoid of life, emptied of all human reference, all continuities of scale and space which would connect the viewer to the landscape. Yet in the intensity with which it fixes on its motif, and in the way it arrests the viewer by its very focus on the unremarkable, the canvas fashions about itself a humanizing plot. This story might read: someone, perhaps a traveller through the countryside, has paused to behold a certain group of alders. What has captured his gaze remains uncertain. Perhaps he admires the sublime contrast of slender branches set against an inscrutable ground of snow, fog and clouds; perhaps he believes that the alders, in their lifeless, inhospitable form, harbour some secret message for him about himself or about the world, ‘thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears’. The canvas simply depicts what the traveller saw. To the viewer, meaning is merely indicated, never confirmed. Each clod of earth in the foreground, for example, is punctuated by a dark spot, like the entrance to a burrow. Against the wanderer’s exile and estrangement might thus be set a condition of refuge and dwelling. The four clods, moreover, correspond in number and position to the main alder stems that grow above, suggesting a graveyard allegory of death and life. The tiny patch of pale blue sky at the upper right, which eases the dull monochromy of the winter scene, embellishes this reading: against the death-in-life of earthly existence, the canvas offers a vision of transcendence, hence the formal caesura between the detailed and mundane foreground (the finite) and the boundless, horizonless distance (the infinite). The particular content of such plots or allegories are less important than their felt presence within your experience of the canvas. If nothing else, they shape the thicket into a meaningful object, excavating it from a larger passage through inanimate nature (the traveller’s journey, say) and inhabiting it with an uncertain, but totalizing subjectivity, as the picture of an experience of a thicket.

You are placed before a thicket. You seek entrance to that which commands your attention. The scene becomes an extension of yourself, a buried meaning, an experience half-remembered, or what you will. You believe that, because this is a painted scene, it is somehow for you, and that insignificant nature, represented, will have a bearing on your life. Frozen in your passage before the canvas, however, like a moth drawn towards a flame, you discover your kinship with the canvas: object among objects.

You are placed before a grove of fir trees in the snow (illus. 2). The trees and pale blue sky create an architecture ordered around your gaze and coincident with the canvas’s geometry. The tallest fir, stationed at the middle of the painting, establishes the central axis of a rigorous symmetry that commands the whole. This symmetry is tempered throughout by a natural randomness of detail. Thus, for example, the two large trees that flank the central fir, as well as the pair of saplings planted in the foreground, are not matched exactly in size, shape or placement within the visual field. And the diagonal rising right to left, carried by the snowy upper branches of smaller trees before the central fir, finds nowhere a corresponding diagonal rising left to right. Such apparent inconsistencies, however, are always gauged against that prevailing rage for order that points the centre tree’s snow-capped tip at the precise midpoint of the picture’s upper framing edge, and that divides the canvas horizontally into perfect halves where the sky reaches down between the right and central firs. The grove’s episodes of asymmetry and randomness, its excursions into the accidental and particular, function merely to place the picture’s order within the natural world. They assure you that the geometry you see does not belong to the canvas alone, but is coextensive with the grove itself, which seems somehow to have grown precisely to accommodate and frame your gaze. The uncanny coincidence between natural object and pictorial order emerges partly from the shape of the represented objects. Fir trees generally take the form of upright isosceles triangles, and their boughs, twigs and needles establish diagonals which rise upward from their stem, contrapuntal to the trees’ shoulders. The bilateral symmetry of the fir grove before you, and its construction out of diagonals, out of fir trees rising from the ground and triangular slices of blue sky descending from above, becomes generalized, ubiquitous. Within this grove of firs, anywhere you look you will be placed before the same basic order, the same reciprocity between your gaze and its object, your body (itself symmetrical and tapering towards the top) and the world.

2 Fir Trees in the Snow, 1828. Ernst von Siemens-Kunstfonds, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlung, Munich.

The picture does not so much place you as embrace you. It fashions before you a small space flanked by saplings and celebrated by symmetry: a clearing sized to a body such as yours. The grove becomes a frame for your gaze, a natural altarpiece with you as its single, consecrated object. Its inclusive form, which asserts that order resides in the things themselves rather than in the specific constellation of the visible viewed from one point in space, assures you that such altars, once recognized, are everywhere discoverable.

This scene of a grove of fir trees immediately invites comparison with the image of the alder thicket in the snow. Painted thinly in oil on identically sized canvases, both pictures station you before a single, unremarkable fragment of a winter landscape. Both are devoid of all human reference, all traces of culture, history or plot, save whatever subjectivity is implied in the image’s intense and centralizing focus. And both depict their objects – bare and evergreen trees – from close up, creating a scene that is pure foreground, and that therefore resists spatialization into a larger landscape, or into a continuity of scale with your world (although the fir grove and alder thicket appear roughly similar in size both to each other and to their implied viewers). Such obvious correspondences between the two pictures, the sense you have of their belonging together as a pair, only heightens differences within your experience of each image. Against the concave strip of snow and clods before the alders, which serves to exclude you from the space of the thicket, the fir trees gather about a concave foreground that surrounds you, establishing you as the grove’s potential centre. Against the random and singular pattern of bare branches silhouetted against the sky and viewed from one particular point, the fir grove posits a ubiquity of order independent of your gaze and spread throughout the landscape. Against the barrenness of the alder branches, which allow or even compel your gaze to pass through them to an indeterminate distance of uncertain substance and structure, the fir trees, ever green, form an impenetrable barrier to your vision, inviting you to remain where you are, at the centre of this natural architecture. And against a thin and empty world of absences, of branches overlapped on branches overlapped upon a void, the fir grove founds presences even in winter: the opaque boughs against a clear blue sky, the undisturbed silhouetting of the snow-tipped foreground saplings against the dark, snowless bases of the larger trees, the self-presence of the viewer in a quasi-sacral space. Such contrasts transcend the simple distinctions of a bare and leafy tree, frozen and partly thawing ground, dull and cheerful sky, which might inscribe the companion pieces into some traditional allegory, say, of death and life. These pictures compare not so much the objects in a world, as your experience of the world. They display you to yourself in your various orientations toward the things you see, the spaces you inhabit and the infinities you desire. Thicket and grove are thus not paired primarily through analogies of composition, scale, canvas size or motif, but rather through their shared address of an experiencing subject. They are linked together, that is, as episodes in a single passage, ‘experiences’ metaphorized as moments within a journey when the wanderer pauses and beholds.

In exactly whose experience, though, are these two moments finally linked? The alders and the firs betray no evidence of earlier travellers to their site, no sign that you, the viewer, are not the first and only person to pause before these winter scenes. And yet something in these canvases eludes the immediacy of your experience, insisting that the firs and alders are not, and never were, moments within your life. Each picture depicts a radically unremarkable nature, purged of human meaning and therefore of any clear relation to yourself, within a composition so centralized and intensely focused that it appears endowed with a quite particular and momentous significance. This significance eludes you, and you stand before the pictures as before answers for which the questions have been lost. They are fragments of an experience of nature elevated to the level of a revelation, a revelation, however, whose agent and whose content have long since disappeared.

You are placed before the grove of fir trees in the snow, just as you were placed before the thicket of alders, and the solitude that confronts you begins to swell. It has inhabited the empty reaches of the winter landscape, and it unfolds past the place where the original wanderer, hesitating in his path, took note of what nature revealed to him. This solitude expands beyond the picture frame, now beyond this voice that speaks here. And it confronts you with the image of your true arrival to the landscape, your embarkation on a Winterreise: while you are placed before these winter scenes, the foreground snow before the alders and the firs lies empty still.

In a very simple sense, Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings of the thicket and the grove, now kept in Dresden and Munich respectively, are linked together by a subject anterior to the viewer. At around 1900, the two canvases hung in a private collection in Stuttgart, where they bore the title Aus der Dresdner Heide I and II (From the Dresden Heath I and II). Their owner was a descendant of one of Friedrich’s first and most ardent supporters, the Berlin publisher and nationalist Georg A. Reimer, who was born in the artist’s own hometown of Greifswald in Swedish Pomerania just two years after Friedrich’s birth in 1774. Reimer must have purchased the works sometime around 1828, when they seem to have ...