![]()

1

Design Ideals, Design Reform,

Design Professions, 1870–1914

Far more important than ruling the world . . . is giving the world a face. The nation to achieve this will be truly the leader of the world, and Germany must become that nation.

Hermann Muthesius, ‘Die Zukunft der Deutschen Form’,19151

The beginning of the twentieth century in Germany was marked by an increasing self-confidence about the possibilities for an emergent design culture that could hold its own on the world stage. During the decade leading up to 1915, when Hermann Muthesius, a Prussian senior civil servant and important commentator on architecture, design and industrial culture made this pronouncement under the title of ‘The Future of German Form’, he had been one of Germany’s strongest advocates for promoting relations between art and industry. In part taking the model from Britain, where he had been posted between 1896 and 1904 as cultural attaché in the German embassy in London, Muthesius was one of the first of the generation to rally around the call for design reform in the new nation state of Germany. This was most clearly expressed in his important three-volume study Das Englische Haus (The English House) of 1904–5 and in his writings for the Deutsche Werkbund from 1907, an organization of which he was a founding member. Merely twenty years earlier, it would have seemed impossible for a commentator to make such a claim for Germany to hold this position. Muthesius’s comment came after years of prescriptive writing about design by himself and other like-minded figures, at all levels, to help elevate the designer for industry, so that the designer’s role would be acknowledged as essential for the well-being of the national economy and its success abroad. Made during the first year of the First World War, Muthesius’s suggestions were therefore not out of the question, even if they would still be deemed controversial.

The Argument for Kunstindustrie

The debate on the correct education for the fine artist, applied artist and designer in Germany mounted during the second half of the nineteenth century. Underlying this was the concern to introduce a greater dialogue between the trade schools and the art academies, which evolved into quite separate institutions responsible for different forms of visual art education. Their separation was based on idealist philosophical thought, initially stemming from a distinction made by Immanuel Kant in his essay, The Critique of Judgement of 1790. In this, Kant distinguished two kinds of beauty, free beauty (pulchritude vaga), which he associated with expression in the fine arts, and dependent or applied beauty (pulchritude adhaerens), which he defined particularly in relation to use in architecture and design. Kant wrote:

In architecture the chief point is a certain use of the artistic object to which, as the condition, the aesthetic ideas are limited. In sculpture the mere expression of aesthetic ideas is the main intention. Thus statues of men, gods, animals, etc., belong to sculpture; but temples, splendid buildings for public concourse, or even dwelling-houses, triumphal arches, columns, mausoleums, etc., erected as monuments, belong to architecture, and in fact all household furniture (the work of cabinet-makers, and so forth – things meant to be used) may be added to the list, on the ground that adaptation of the product to a particular use is the essential element in a work of architecture.2

The mounting interest in the new art industries – Kunstindustrie, as they were to be called – might achieve a reconciliation of this Kantian separation. This belief was held in a number of quarters, which should be explored to shed further light on how Muthesius’s pronouncement of 1915 came to be made. It was in the 1860s and ’70s that the question of the quality of Germany’s industrial manufacture was first raised with increased intensity. Under the term Kunstindustrie fell the various skills and trades associated with the manufacture of industrial items, ranging from ceramics and glass to metalwork, textiles, furniture and woodwork. These goods could be for domestic use in the home or, in many cases, they formed the basis to equip the business and commercial enterprises that were proliferating at this time of rapid urbanization in Germany. In terms of their manufacture, by the late nineteenth century the factory system was challenging smaller-scale industries, driven by profit and replacing handwork by machine-tooling. This often undermined the previously close connection between maker, designer and finished product, with the possibility of decline in the quality of goods becoming a major issue.

For Germany, the debate began initially in its new capital, Berlin, where Hermann Schwabe, a civil servant and university professor, led the Statistics Bureau from 1865 and held a lively interest in the general well-being of the cultural life of the city.3 Schwabe was sent to Britain as a government emissary to report on art and design education, and in 1871 he published his recommendations in the book Kunstindustrie Bestrebungen in Deutschland (Aspirations for Art Industry in Germany). This publication, the first of its kind, held important implications for the Deutsche Gewerbe Museum (German Trade Museum), which along with the accompanying Unterrichtsanstalt (Teaching Institute) had opened in 1867.4 The publication formed the most complete exploration of the possibilities of educating future generations of the skilled workforce, including designers, for Germany’s art industries.

Schwabe proposed a system for educational institutions that he hoped would be implemented by the government. He went so far as to offer sample curricula for students and teachers and gave advice on building up study collections and organizing exhibitions. Schwabe was well aware of developments in other countries, in particular Britain, where what became known as the South Kensington system had evolved between 1837 and 1852. According to this model, the Government School of Design and National Art Training School (which in 1896 became the Royal College of Art) taught principles of design and what were considered the ‘true principles’ of ornament. An accompanying museum, in the London case the South Kensington Museum, eventually opened in 1857 and was renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899. The idea was to build collections of historical and contemporary artefacts ranging across materials and techniques. These were intended to be exemplars, object lessons in technique, use of material, artistic form and ornament, for the instruction of future generations of artisans, designers and architects.5

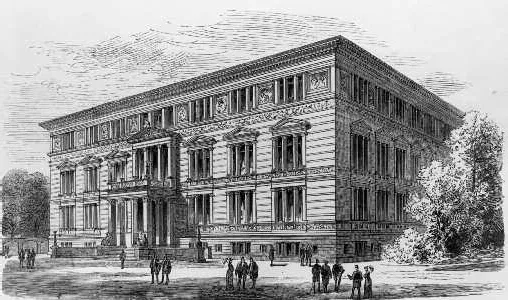

Print of the facade of the Berlin Kunstgewerbemuseum, designed by the architects Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden, 1877–81.

A German connection already existed through the figure of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, husband to Queen Victoria and royal consort, who, together with Henry Cole, Francis Fuller, Charles Dilke and other members of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, was largely responsible for the Great Exhibition of 1851. As royal patron, Prince Albert subsequently commissioned the architect Gottfried Semper, at the time a political refugee from Prussia, to assist in guiding the curatorial divisions of the museum, once the school’s original collections had been greatly enhanced through the acquisitions from the Crystal Palace exhibition. Semper’s influential scheme was to elide historical and cultural difference, organizing the museum departments instead by material. Accordingly, the first departments were Wood, Metal, Ceramics, Textiles and Engraving. Semper’s major study of applied and decorative arts, Der Stil in der technischen und tektonischen Künsten of 1860–62 (Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts; or, Practical Aesthetics) was to prove extremely important for laying down the intellectual foundations for a theory of the applied arts. According to Michael Conforti, Semper ‘disregarded subject matter, which had been the foundation of academic criticism since the sixteenth century’, focusing instead on ‘the symbolic nature of individual motifs in objects and the transformation of their meaning in varying situations of production and cultural environments’.6

True to his age, Schwabe divided the education of the artist and designer into clear stages. Evolutionary models of thought were popular since the publication in 1859 of Charles Darwin’s highly influential On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection; or, The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. In this, a theory of humankind was cast in developmental steps from the ‘primitive’ to the sophisticated or civilized, and in many systems of classification, including theories of ornament, similar models were proposed.7

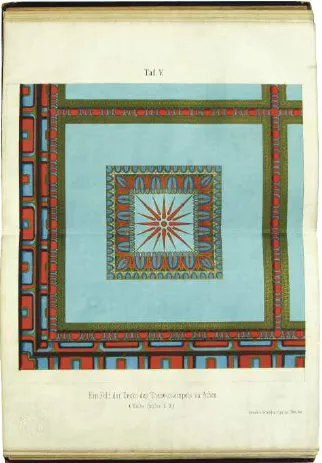

In this respect, Schwabe’s argument and curricula were no exceptions. For instance, he ran through the essential ingredients for preparing an art handworker in the knowledge of design applied to a variety of materials. Drawing was the primary skill, taught first in ‘principles of ornament’, then plant and animal form. This was followed by exercises in applied forms for the design of objects, intended for all areas of the art industries. The method was no doubt developed in the knowledge of Owen Jones’s important study, The Grammar of Ornament (1856), through which an accomplished designer could develop a lexicon of ideas that would then be ‘applied’ to the material in hand.8 A second level of drawing, Schwabe suggested, could lead the student from the linear and two-dimensional to rendering three-dimensional form, introducing the treatment of shading and colour and the ability to depict the complete object in preparation of its realization. Third came lessons in modelling from the human form. It is important to note that in all of this, ‘design’ was considered to be an exercise on paper, undertaken in a classroom, often following the exact instruction of the master, removed from actual materials of manufacture. Students were therefore expected to take their new knowledge back to the workshop or factory and apply the lessons learnt in the activity of making.

Gottfried Semper, Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten, originally published in 1862. This page shows the ceiling decoration from the Temple of Theseus, Athens.

At the time of Schwabe’s writing most students were men. It was only in the 1880s that separate art schools for women were opened in Germany, allowing opportunities to study all aspects of art and design, including in the life room. This growth was noticeable when distinctly more middle-class women became known in their own right in the early 1900s as important craftswomen, engravers, book artists, embroiderers, weavers and potters. On the education of women, in the 1870s Schwabe could offer only the following comment: ‘Classes for women are an integral part of drawing school, although their introduction leaves something to be desired. Where they are introduced, they should be considered supplementary to the rest of the drawing classes.’9

Students in the metal workshop at the Berlin Kunstgewerbeschule, c. 1910, showing the importance of learning through making.

Since classes were intended for those who were employed during the day, many took place in the evenings, and others on Sundays. The latter were organized, Schwabe noted, particularly for craftsmen in the construction and machine-building trades. A special group of classes for composition and the applied arts covered elementary and ornamental drawing, painting and drawing after the plaster cast and figurative drawing, with lectures on anatomy and proportion. Again, following the examples of London and, more recently, Vienna, where director Rudolf von Eitelberger had established the Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Austrian Museum of Art and Industry) in 1862 on South Kensington lines, Schwabe proposed the formation of a collection of exemplary objects. His description ran:

This now fills four halls, of which the last one opened in July of this year. It contains carvings made of various materials, furniture and a collection of plaster casts, which have already increased in number to about 600; roughly 130 of these, which are particularly suited as exemplars for education, are cast and sold cheaply in the museum. The remaining three halls feature especially wickerwork, textiles, lace, blown and cut glass, porcelain and clay goods, mosaics, enamelled and lacquer work, as well as cast and wrought iron as exemplary or historically interesting pieces from various countries and time periods.10

This ambitious list was intended to supplement the existing collections of the museum, at first known as the Deutsches Gewerbe Museum (German Trade Museum). By 1880, growing in importance, the museum moved to a neo-Renaissance building designed by Martin Gropius, itself modelled on the South Kensington Museum, under the leadership of its renowned director Julius Lessing. In 1885 it was renamed the Königliches Kunstgewerbe Museum (Arts and Crafts Museum of the Royal Collections). Although Berlin was the first German city to take up such an initiative, other cities soon followed by founding museums dedicated to the applied arts, notably Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig, Nuremberg and Munich.11

In order to convince his audience of politicians and senior civil servants, Schwabe made predictions of the number of visitors such a museum might attract. Initial comparison was made with London, where the annual visitor figure for the South Kensington Museum in 1869 was thought to be 800,000, while in Vienna it was approximately 108,000. The Berlin museum, which was, as Schwabe stressed, still a teaching rather than a public institution, could claim only the exact figure of 11,757.12 Important for his mission was the list of possible venues for travelling exhibitions, made up of art and trades schools in smaller towns and cities across Germany. It was through such a programme that educating the taste of the public would be fulfilled. He wrote:

However, the German trade museum has taken another important step. In order to generalize the beneficial effect of its aspirations for industry, it has also founded a touring...