![]()

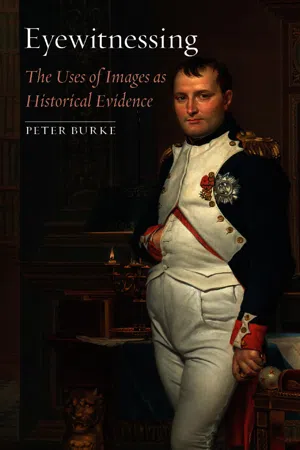

1 Photographs and Portraits

While photographs may not lie, liars may photograph.

LEWIS HINE

The temptations of realism, more exactly of taking an image for reality, are particularly seductive in the case of photographs and portraits. For this reason these kinds of image will now be analysed in some detail.

Photographic Realism

From an early date in the history of photography, the new medium was discussed as an aid to history. In a lecture delivered in 1888, for example, George Francis urged the systematic collection of photographs as ‘the best possible picturing of our lands, buildings and ways of living’. The problem for historians is whether, and to what extent, these pictures can be trusted. It has often been said that ‘the camera never lies’. There still remains a temptation in our ‘snapshot culture’, in which so many of us record our families and holidays on film, to treat paintings as the equivalent of these photographs and so to expect realistic representations from historians and artists alike.

Indeed, it is possible that our sense of historical knowledge has been transformed by photography. As the French writer Paul Valéry (1871–1945) once suggested, our criteria of historical veracity have come to include the question, ‘Could such and such a fact, as it is narrated, have been photographed?’ Newspapers have long been using photographs as evidence of authenticity. Like television images, these photographs make a powerful contribution to what the critic Roland Barthes (1915–1980) has called the ‘reality effect’. In the case of old photographs of cities, for example, especially when they are enlarged to fill a wall, the viewer may well experience a vivid sensation that he or she could enter the photograph and walk down the street.1

The problem with Valéry’s question is that it implies a contrast between subjective narrative and ‘objective’ or ‘documentary’ photography. This view is widely shared, or at least it used to be. The idea of objectivity, put forward by early photographers, was supported by the argument that the objects themselves leave traces on the photographic plate when it is exposed to the light, so that the resulting image is not the work of human hands but of the ‘pencil of nature’. As for the phrase ‘documentary photography’, it came into use in the 1930s in the USA (shortly after the phrase ‘documentary film’), to refer to scenes from the everyday life of ordinary people, especially the poor, as seen through the lenses of, for instance, Jacob Riis (1849–1914), Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), and Lewis Hine (1874–1940), who studied sociology at Columbia University and called his work ‘Social Photography’.2

However, these ‘documents’ (illus. 63, for example) need to be placed in context. This is not always easy in the case of photographs, since the identity of the sitters and the photographers is so often unknown, and the photographs themselves, originally – in many cases, at least – part of a series, have become detached from the project or the album in which they were originally displayed, to end up in archives or museums. However, in famous cases like the ‘documents’ made by Riis, Lange and Hine, something can be said about the social and political context of the photographs. They were made as publicity for campaigns of social reform and in the service of institutions such as the Charity Organisation Society, the National Child Labour Committee and the California State Emergency Relief Administration. Hence their focus, for instance, on child labour, on work accidents and on life in slums. (Photographs made a similar contribution to campaigns for slum clearance in England.) These images were generally designed to appeal to the sympathies of the viewers.

In any case, the selection of subjects and even the poses of early photographs often followed that of paintings, woodcuts and engravings, while more recent photographs quoted or alluded to earlier ones. The texture of the photograph also conveys a message. To take Sarah Graham-Brown’s example, ‘a soft sepia print can produce a calm aura of “things past”‘, while a black-and-white image may ‘convey a sense of harsh “reality”’.3

The film historian Siegfried Kracauer (1889–1966) once compared Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886), for a long time the symbol of objective history, with Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), who was more or less his contemporary, in order to make the point that historians, like photographers, select which aspects of the real world to portray. ‘All great photographers have felt free to select motif, frame, lens, filter, emulsion and grain according to their sensibilities. Was it otherwise with Ranke?’ The photographer Roy Stryker had made the same essential point in 1940. ‘The moment that a photographer selects a subject’, he wrote, ‘he is working upon the basis of a bias that is parallel to the bias expressed by a historian.’4

On occasion, photographers have gone well beyond mere selection. Before the 1880s, in the age of the tripod camera and twenty-second exposures, photographers composed scenes by telling people where to stand and how to behave (as in group photographs to this day), whether they were working in the studio or in the open air. They sometimes constructed their scenes of social life according to the familiar conventions of genre painting, especially Dutch scenes of taverns, peasants, markets and so on (Chapter 6). Looking back on the discovery of photographs by British social historians in the 1960s, Raphael Samuel commented somewhat ruefully on ‘our ignorance of the artifices of Victorian photography’, noting that ‘much of what we reproduced so lovingly and annotated (as we believed) so meticulously was fake – painterly in origin and intention even if it was documentary in form’. For example, to create O. G. Rejlander’s famous image of a shivering street urchin, the photographer ‘paid a Wolverhampton boy five shillings for the sitting, dressed him up in rags and smudged his face with the appropriate soot’.5

Some photographers intervened more than others to arrange objects and people. For example, in the images she shot of rural poverty in the USA in the 1930s, Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), who worked for the magazines Fortune and Life, was more interventionist than Dorothea Lange. Again, some of the ‘corpses’ to be seen in photographs of the American Civil War (illus. 5) were apparently living soldiers who obligingly posed for the camera. The authenticity of the most famous photograph of the Spanish Civil War, Robert Capa’s Death of a Soldier, first published in a French magazine in 1936 (illus. 4), has been challenged on similar grounds. For these and other reasons it has been argued that ‘Photographs are never evidence of history: they are themselves the historical.’6

This is surely too negative a judgement: like other forms of evidence, photographs are both. They are particularly valuable, for instance, as evidence of the material culture of the past (Chapter 5). In the case of Edwardian photographs, as the historical introduction to a book of reproductions has pointed out, ‘we can see how the rich dressed, their posture and demeanour, the restrictiveness of Edwardian dress for women, the elaborate materialism of a culture which believed that wealth, status and property ought to be openly paraded’. The phrase ‘candid camera’, coined in the 1920s, makes a genuine point, even though the camera has to be held by someone and some photographers are more candid than others.

4 Robert Capa, Death of a Soldier, 1936, photograph.

5 Timothy O’Sullivan (negative) and Alexander Gardner (positive), A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, July, 1863, pl. 36 of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, 2 vols (Washington, DC, 1865–6).

Source criticism is essential. As the art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) perceptively observed, the evidence of photographs ‘is of great use if you know how to cross-examine them’. A spectacular example of this kind of cross-examination is the use of aerial photography (originally developed as a means of reconnaissance in the First and Second World Wars), by historians, notably historians of medieval agriculture and monasticism. The aerial photograph, which ‘combines the data of a photograph with that of a plan’ and records variations in the surface of the land which are invisible to people on the ground, has revealed the arrangement of the strips of land cultivated by different families, the locations of deserted villages, and the layout of abbeys. It makes possible the reconnaissance of the past.7

The Portrait, Mirror or Symbolic Form?

As in the case of photographs, many of us have a strong impulse to view portraits as accurate representations, snapshots or mirror images of a particular sitter as he or she looked at a particular moment. This impulse needs to be resisted for several reasons. In the first place, the painted portrait is an artistic genre that, like other genres, is composed according to a system of conventions which changes only slowly over time. The postures and gestures of the sitters and the accessories or objects represented in their vicinity follow a pattern and are often loaded with symbolic meaning. In that sense a portrait is a symbolic form.8

In the second place, the conventions of the genre have a purpose, to present the sitters in a particular way, usually favourable – although the possibility that Goya was satirizing the sitters in his famous Charles IV and Family (1800) should not be forgotten. The fifteenth-century Duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltre, who had lost an eye in a tournament, was always represented in profile. The protruding jaw of the emperor Charles V is known to posterity only through the unflattering reports of foreign ambassadors, since painters (including Titian) disguised the deformity. Sitters generally put on their best clothes to be painted, so that historians would be ill advised to treat portraits as evidence of everyday costume.

6 Thomas Gainsborough, Mrs. Philip Thicknesse, née Anne Ford, 1760, oil on canvas. Cincinatti Art Museum.

It is likely that sitters were also on their best behaviour, especially in portraits made before 1900, in the sense of making gestures, or of allowing themselves to be represented as making gestures, which were more elegant than usual. Thus the portrait is not so much a painted equivalent of a ‘candid camera’ as a record of what the sociologist Erving Goffman has described as ‘the presentation of self’, a process in which artist and sitter generally colluded. The conventions of self-representation were more or less informal according to the sitter or indeed the period. In England in the later eighteenth century, for example, there was a moment of what might be called ‘stylized informality’, which may be illustrated by the painting of Sir Brooke Boothby lying on the ground in a forest with a book (illus. 51). However, this informality had its limits, some of them revealed by the shocked reactions of contemporaries to Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait of Mrs Thicknesse, who was represented crossing her legs under her skirt (illus. 6). One lady remarked that ‘I should be sorry to have any one I loved set forth in such a manner’. By contrast, in the later twentieth century, the same posture on the part of Princess Diana in Bryan Organ’s famous portrait could be taken to be normal.

The accessories represented together with the sitters generally reinforce their self-representations. These accessories may be regarded as ‘properties’ in the theatrical sense of the term. Classical columns stand for the glories of ancient Rome, while throne-like chairs give the sitters a regal appearance. Certain symbolic objects refer to specific social roles. In an otherwise illusionistic portrait by Joshua Reynolds, the huge key held by the sitter is there to signify that he is the Governor of Gibraltar (illus. 7). Living accessories also make their appearance. In Italian Renaissance art, for example, a large dog in a male portrait is generally associated with hunting and so with aristocratic masculinity, while a small dog in a portrait of a woman or a married couple probably symbolizes fidelity (implying that wife is to husband as dog is to human). 9

7 Joshua Reynolds, Lord Heathfield, Governor of Gibraltar, 1787, oil on canvas. National Gallery, London.

8 Joseph-Siffréde Duplessis, Louis XVI in Coronation Robes, c. 1770s, oil on canvas. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Some of these conventions survived and were democratized in the age of the photographic studio portrait, from the mid nineteenth century onwards. Camouflaging the differences between social classes, the photographers offered their clients what has been called ‘temporar...