![]()

1

‘The [Glass] House’: Christ Church, Oxford

BEFORE VENTURING FURTHER AFIELD with Carroll in his pursuit of photographs, I want to begin at Christ Church, Oxford, commonly known as ‘the House’, and effectively his home for 47 years. It was here on 1 July 1876 that Alexandra Kitchin (1864–1925), one of the children to whom Carroll alludes in his letter to Dolly Draper, crossed Tom Quad chaperoned by her mother, on her way to have her photograph taken. Not at a professional studio, however, but at the photographic studio built above Carroll’s college rooms. Arriving there, Xie, as she was affectionately known, donned a mob-cap and fancy costume to pose in the guise of Joshua Reynolds’s Penelope Boothby, painted in 1788 (illus. 5). The daughter of the historian and Student of Christ Church George William Kitchin, Xie was one a string of little girls who, over the course of a three-month period, had filed into that most traditional of Oxford colleges to be photographed. Prior to the sitting, in all likelihood she had enjoyed a picnic of Bath buns in Carroll’s sitting room and the chance to play with a mechanical bear and talking doll emptied from the cupboard there. But the highlight of the visit was to pose for the camera and afterwards steal into the mysterious darkroom to be allowed to watch a ghostly form appear upon the glass plate of the negative.

Four years earlier, in February 1872, Carroll had moved into his purpose-built studio.1 Close at hand he enjoyed the convenience of a dedicated darkroom and a changing room for models. From March of that year he began taking photographs there and was able to operate like a proper photographer; a situation he had long wished for. In the new facility, Carroll had space to house his negatives rather than store them with commercial printers, while the roof provided a place to set out printing frames for exposure to the sun. Writing on 11 May of that year to Mary MacDonald, the daughter of his contemporary and friend the novelist and clergyman George MacDonald, Carroll notes that he is ‘taking pictures almost every day’ and were she to ‘bring [to Oxford her] best theatrical “get up”’ he would make ‘a splendid picture’ of her.2 He carried on taking photographs at a rapid rate; the glass structure reduced exposure times allowing photography more easily in dull weather. Between May and July of 1873, for example, Xie Kitchin, Alice, Ida and Carry Mason, Julia and Ethel Arnold, Herbert Kitchin, Lily Bruce, Miss Ward, Miss Jones, Margaret and Frederica Morell, Isabel Fane, Maud, Isabel and Helen Standen and Beatrice and Ethel Hatch all came to be photographed: six of them on more than one occasion.3

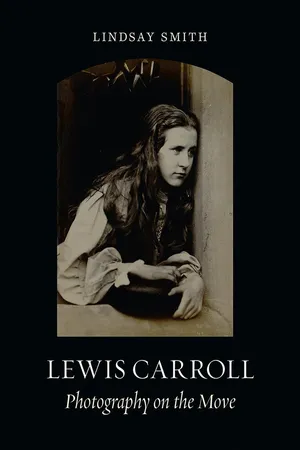

5 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), ‘Penelope Boothby’ (standing), 1876, albumen print.

6 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Alice Liddell, 25 June 1870, albumen carte de visite.

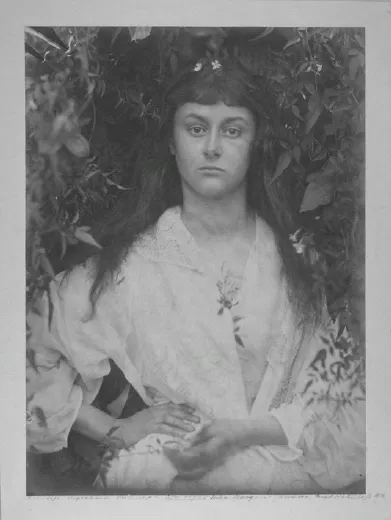

7 Julia Margaret Cameron, Alethea, 1872, albumen print.

It must have been a strange sight in the all-male context of Christ Church, and of Oxford colleges more generally, to witness figures of little girls entering and leaving. Prior to this period, during the late 1850s and early 1860s, Carroll had enjoyed a ready supply of child subjects at the nearby Deanery. Henry George Liddell, who had succeeded Thomas Gaisford as Dean of Christ Church in June 1855, had had six children growing up there, four of whom Carroll had photographed regularly in the garden.4 By 1876 Alice Pleasance Liddell, the inspiration for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), was a woman of 24. She had last sat for Carroll to take her picture on 25 June 1870 at the age of eighteen (illus. 6). On 24 April 1873, on visiting the Dean, the author of the Alice books had been invited into the drawing room by Lorina Liddell senior to view new photographs of her daughters and Alice had proudly shown him three of herself by his contemporary amateur Julia Margaret Cameron. The Alice Carroll had captured in his own photographs of the 1850s and ’60s had been transformed by Cameron’s large-format images into the mature goddesses of ‘Alethea’ (illus. 7), ‘Pomona’ (illus. 8) and ‘St Agnes’.5

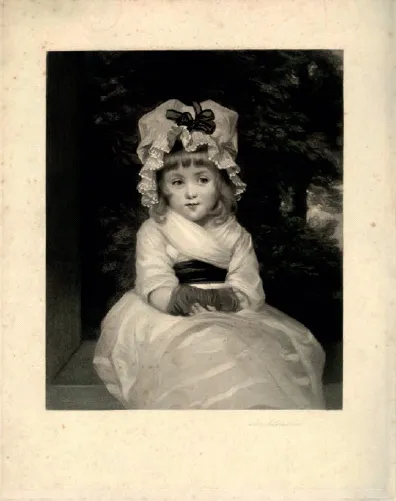

By contrast, on her visit to be photographed in 1876, Xie Kitchin was still a minor and she belonged to a third generation of Carroll’s ‘child-friends’. Four successful prints survive from that session. Two of them create the persona of ‘Penelope Boothby’ from Reynolds’s celebrated portrait of the three-year-old daughter of Sir Brooke Boothby. That portrait had become retrospectively imbued with significance following the child’s death in 1791 and remained popular in the 1870s in the form of Samuel Cousins’s mezzotint after the painting (illus. 9). Mourning the loss of his six-year-old daughter, Boothby had commissioned a marble funerary monument from the sculptor Thomas Banks and published a collection of his own commemorative verses.6 In 1793, with the exhibit of ‘the plaster model for the final sculpture’, many were deeply moved by its portrayal of the apparent life of a sleeping child.7 When Carroll recalled ‘Penelope Boothby’, therefore, he referred photographically to a child associated in cultural memory with public outpourings of grief.

8 Julia Margaret Cameron, Pomona, 1872, albumen print.

In the standing version of Carroll’s Penelope Boothby (see illus. 5), Xie Kitchin poses centrally against the wall, her left hand displaying a half-opened fan. Apart from the child’s white mob-cap with its dark ribbon, and her dark fingerless gloves, there is little to suggest the original. Carroll attempts to recreate with a shawl her white crossed bodice and gives his subject a similar, though narrower, sash. Other details, by comparison, the striped stockings, decorative sleeves, black choker with heavy metal cross and printed overskirt, are his invention and much fussier than their painted counterparts. Even the signature mob-cap of Reynolds’s original, its caul barely generous enough to accommodate her hair, appears perched awkwardly on Xie Kitchin’s head. With her eye-line directed slightly off to the left, the child holds a sombre expression. In Carroll’s seated version of the photograph, with her chin resting on her hand, she adapts a distinctly mature pose (illus. 10). In so doing the twelve-year-old turns the faraway look of Reynolds’s infant subject into a direct unflinching gaze into the camera lens.

9 Samuel Cousins, Penelope Boothby, mezzotint after Sir Joshua Reynolds, published 1874.

Carroll’s choice of the persona of Penelope Boothby as photographic subject emphasizes the enduring significance to him of dressing up children to photograph, bringing to mind one of his earliest in the genre, and his best-known child portrait, Alice Liddell as ‘The Beggar Maid’ (illus. 11). Possibly intended as a companion piece to the less familiar Alice Liddell Dressed in her Best Outfit, and conceivably taken on the same day in 1858,8 this now controversial image of a child dressed in rags, posed begging for alms, refers to the story of the ancient African King Cophetua and his ‘beggar maid’, resurrected by poets in the nineteenth century (illus. 12). Alfred Tennyson’s ‘The Beggar Maid’, written in 1833 and published in Poems (1842), was most likely an inspiration for Carroll’s photograph.9 As the speaker of the poem relates the admiration of onlookers for the beggar’s rare attributes, ‘more fair than words can say’, the reader, like the viewer of Carroll’s photograph, is invited to see through her ‘poor attire’. Her clothing is at the same time, however, key to her unparalleled attraction.

10 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), ‘Penelope Boothby’ (seated), 1876, albumen print.

11 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Alice Liddell as ‘The Beggar Maid’, 1858, albumen print.

12 Julia Margaret Cameron, King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid, 1875, albumen print.

The register of Carroll’s ‘Beggar Maid’ alters when read against its ‘companion’ photograph Alice Liddell Dressed in her Best Outfit, which shows a clean upper middle-class child. Pictured in ragged clothing Alice personates the street Arab in a popular conceit of the period but, changing her back into neat contemporary Victorian dress, Carroll explores the difference between the two states in a ‘before and after’ that overtly signals the more subtle metamorphic potential of photography. The persona of a beggar maid, however, was not a photographic one-off for Carroll. Xie Kitchin also posed in the role that would become synonymous with Carroll’s celebrated likeness of ‘Alice’. In so doing, she joined others who had ‘sat’ for his camera in the ‘beggar’ dress. As a photographer, choreographing successive children in the same roles, he took particular pleasure in capturing qualities of resemblance.10

But in his take on ‘Penelope Boothby’ Carroll raises the additional spectre of infant mortality that haunted nineteenth-century photographic portraits more generally as it had done earlier painted and sculpted ones. Referencing a painted portrait commemorating a dead child, Carroll’s photograph calls to mind a particular state of arrested development. In evoking Reynolds’s younger subject, Carroll alludes to a quality peculiar to the infant that the poet and essayist James Henry Leigh Hunt had earlier uniquely captured in his essay ‘Deaths of Little Children’.11 Written in 1820, at a time of high infant mortality, Hunt’s piece theorizes the impact upon adults of the deaths of children. He regards such loss as a ‘bitter’ necessity ‘thrown into the cup of humanity’, not because he claims ‘the loss of one child enables us to appreciate those remaining’ but rather because ‘if no deaths ever took place, we should regard every child as a man or woman secured’.12 As a consequence, Hunt further notes, an unbroken connection with infancy would be lost, in which case:

Girls and boys would be future men and women, not present children. They would have attained their full growth in our imaginations, and might as well have been men and women at once. On the other hand, those who have lost an infant are never, as it were, without an infant child. They are the only persons who, in one sense, retain it always.13

Hunt does more than recognize that, by fixing a stage prior to maturity, premature death makes a child immortal. He communicates in powerful terms the enduring identity of a dead child. To lose a child is paradoxically to keep one close, he claims, since that loss prevents an adult self from supplanting the infant one. As the deaths of children prevent their being regarded as incipient adults – and the category of infancy becomes something other than a route to maturity – Hunt anticipates temporal implications essential to photography, not only in the broad sense of what Roland Barthes has called the ‘catastrophe’ of the photograph, its propensity to ‘tell’ death in the future, but by petrifying a child at a point in time such that an owner of a photographic image ‘in one sense, retain[s that child] always’ as uniquely attached to it.

Portraits were Carroll’s preferred photographic genre. Although he took pictures of adults, including a number of eminent contemporaries, it was undoubtedly the case that he enjoyed photographing little girls more than other subjects. His preference for female minors might not have proved so problematical were it not for the fact that within the all-male Oxford college environment he was photographing other people’s daughters. But it is pointless to try to argue, as some have done, that Carroll lacked discrimination and relished just as much photographing objects such as the skeleton of a ‘tunny fish’ for the new Oxford Museum – an unlikely assumption whichever way one looks at it. It is equally important to resist a crude psychobiography in which Carroll’s interest in photographing little girls is read either as a displacement of his feelings as a ‘frustrated bachelor’ or as a straightforward form of perversion.14 These polarized interpretations oversimplify both the place of photographs in his life and also what it meant historically to photograph childr...