![]()

PART ONE

Elaborations

![]()

two

A Very Beautiful Pneumatic Machinery

Just over two centuries ago, just as the machine began to impinge most closely upon human consciousness, and began to twin with it, machinery went mad. Or, what may come to the same thing, the mad became mechanical. They began to dream of machines, complicated dreams of sinister, far-reaching apparatuses. The mad machinery of these dreams is not a machinery out of control – not like the juridical machine of Kafka’s In the Penal Settlement, which ends by systematically disassembling itself. It is a machinery that is mad in its functioning, its madness the madness of its very reliability, its repeatability. For the essential madness of the machine lies in its apparent rationality, the offer it holds out to rationality to find its like in mechanical process. For a sane man to believe seriously that he has become a machine is to become mad. A hundred years after what looks like its first appearance, Victor Tausk would give this machine a name, suggesting that all the machineries of the mad are varieties of or modular components of the mysterious, polymorphous apparatus he calls the ‘influencing machine’. The purpose of this machine, which can be operated by persecuting entities over large distances, is to exert control over the patient’s thoughts and feelings. Tausk explains that the influencing machine typically makes the patient see pictures (and when it does this, it takes the form of a magic lantern or cinematograph); it ‘produces, as well as removes, thoughts and feelings by means of waves or rays or mysterious forces’; it produces motor phenomena in the body, like erections and emissions, by means of ‘air-currents, electricity, magnetism, or x-rays’; it creates indescribable bodily sensations, ‘that in part are sensed as electrical, magnetic, or due to air-currents’; and brings about other bodily symptoms such as abscesses and skin-eruptions.1 But the most important function of the machine is its systematic dealing out of delusion, including, we must suppose, the master-delusion of the influencing machine itself. For the maddest thing about this mad contraption is that it is its own product, that its purpose seems to be to manufacture, maintain and ramify itself. Tausk makes it clear that the influencing machine always has a history, its workings becoming ever more complex and elaborate as the patient’s psychosis becomes more deeply rooted. This is because the machine is also the patient’s strongest defence against his madness, in providing a model and an explanation for how his madness works. The maddest thing about this machine is the knowledge it seems to provide of the workings of the madness, which is to say, of itself. Nowhere are the melancholy-mechanical mad madder than in the image they have and hold on to of their madness.

Psychoanalysis and the varieties of corporealized psychiatry similarly propose more or less mechanical systems as correlatives for the act of thinking. In fact, the influencing machine can be an exquisite parody of the psychoanalytic process itself, especially its tendency to convert the spiritual entities of previous eras (bad spirits and possessing demons) into impersonal forces and agencies – id, ego, superego, repression, cathexis, libido. There is thus a strange concurrence between illness and remedy in the case of mechanical delusions, or delusive machines. Tausk reports a number of cases in which patients felt flows and currents, including that of a man who ‘felt electrical currents streaming through him, which entered the earth through his legs; he produced the current within himself, declaring with pride that that was his power!’ But Tausk matches this conception in his explication of the processes behind the formation of the influencing machine, which requires us to accept the assumption ‘that the libido flows throw the entire body, perhaps like a substance (Freud’s view), and that the integration of the organism is effected by a libido tonus, the oscillations of which correspond to the oscillations of psychic narcissism and object libido’.2 This flow of libido is far from merely metaphorical, since it is capable of bringing about transient swelling of organs, as a result of ‘an overflow of secretion resulting from libidinal charging of organs’.3 Both madness and its analysis are explications of the workings of machinery: of the machinery of delusion in the case of the physician and of the delusive machine of the patient, by which latter is meant the machine produced by delusion and the machine that deals out delusions, especially the delusion of itself.

Though he cannot resist the tendency to treat this machine as though it had an existence independent of its victim – indeed, he has a tendency to speak of it as if there were in fact only one machine – Tausk does not quite permit himself to take this machine seriously. It is after all a delusion. Since the machine is a cod, or counterfeit machine, since it cannot really work as it is supposed to work, Tausk does not feel it necessary to take its surface workings very seriously, to enquire into what kind of machine it may actually be. What matters most of all is to get behind the machine-as-symptom in order to understand the psychic machinery that has produced it. The machine is in the final instance mysterious, for a complete account of its workings cannot be given. Tausk proposes instead a genuine reading of the psychological mechanisms that can by contrast be exhibited and explicated in their totality.

Later explicators of the influencing machine have been more attentive to its details, and in particular to the technological forces and forms that it seems to incorporate. Readers of the elaborate delusions of Daniel Paul Schreber in particular have increasingly drawn attention to the importance of technologies of communication – telegraphs, telephones, radio – in his version of the influencing machine. The tendency has been to read all influencing machines as anticipations of the paranoia associated with such distinctively modern technologies of communication. I want to focus attention on a feature of the physical workings of the influencing machine that has not been subject to so much attention, namely the ways in which they are held to work over space and, more specifically, how they imagine the mechanical manipulation of what fills that space – whether air, ether or some other insubstantial matter. Conjugating a number of systematic accounts of systematic delusions, those in particular of James Tilly Matthews, Friedrich Krauss and John Perceval, I will try to construe the workings of the influencing machine as a pneumatics, or a fluid mechanics.

Gaz-plucking

In the autumn of 1809 a writ for habeas corpus was delivered to Bethlem Hospital demanding the release of an inmate who had been confined in the hospital for 13 years. This led to a hearing before the King’s Bench in which affidavits from the family of the confined lunatic were considered against those furnished by Bethlem Hospital itself. Chief among the affidavits on the side of the confined man was an account by two doctors, one George Birkbeck and his associate Henry Clutterbuck, of their visits to the prisoner over the course of some months, leading to their conclusion that he exhibited no traces of insanity and should be released. Against them, the governors of the hospital brought forward various witnesses as to the confined man’s dangerous insanity, which extended to making threats against the king and his ministers. Most tellingly of all, they quoted a letter of 7 September 1809 from no less a person than Lord Liverpool, the home secretary, recommending that the prisoner continue to be entertained at the public expense in Bethlem Hospital. The case for release was rejected.

It was not usual for the home secretary to be applied to in such a case. It seems likely that it was not in his office but in his person that Lord Liverpool was addressed. For this particular lunatic had first been brought to Bedlam following an outburst he had made on 30 December 1796 from the public gallery of the House of Commons during a speech made by Robert Banks Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool himself, defending the government against the charge that it had deliberately obstructed efforts to avert the costly and damaging war against France. Lord Liverpool’s speech had been interrupted by a cry of ‘Traitor!’ from the gallery and a man had been hustled away by stewards. During his examination by the Bow Street magistrates, it emerged that the prisoner’s name was James Tilly Matthews, who had a wife and young son. Matthews had been a tea merchant, but claimed to have been in the service of the government since just before the outbreak of war against France, acting as an emissary conducting secret peace talks with the revolutionary government. Now the government had decided against peace, seeing their opportunity of crushing decisively the political threat from across the Channel and halting the drift of revolution. Matthews’s sense of betrayal had led to his public denunciation of Lord Liverpool, the minister whom he most particularly blamed for his predicament. The fierce threats that Matthews uttered against Lord Liverpool and other members of the government, combined with his obviously excitable condition, left the Bow Street magistrates with no choice but to request the governors of Bethlem Hospital to take custody of him.

One can perhaps understand why Lord Liverpool might have been disinclined to approve the release of Matthews even thirteen years after this event. The threat posed by somebody like Matthews seemed real. One of Matthews’s fellow detainees in the Bethlem Hospital was James Hadfield, who had fired a pistol at George III in the Drury Lane Theatre on 15 May 1800 and, following the rapid institution of a law to permit the detention of the criminally insane, had also been committed to Bedlam. On 12 May 1812, a couple of years after Matthews’s appeal was turned down, a man armed with a small pistol killed the prime minister, Spencer Perceval, in the lobby of the House of Commons. Twenty years later the son of the assassinated prime minister, who had been nine years old at the time of the murder, would himself be incarcerated in a lunatic asylum. As far as Lord Liverpool was concerned, insurrection was still, twenty years after the French Revolution, in the air. In this, he was in fact in close accord with James Tilly Matthews, especially as regards the air.

The story of what led to the outburst as a result of which James Tilly Matthews was confined in Bethlem Hospital, and why Lord Liverpool should have continued to take an interest in him, has been told a number of times, most recently and in the most fluent and illuminating detail by Mike Jay.4 The most important thing about the 1810 habeas corpus hearing was the effect it had on John Haslam, the resident apothecary and senior medical officer of the Bethlem Hospital, spurring him into publishing an elaborate defence of his view that Matthews was completely insane and unfit to be released. Stung by the challenge to his professional judgement, Haslam was determined to show that Matthews was not only mad, but also epically and self-evidently so. The way to do this was, as he put it, ‘to develop the peculiar opinions of Mr Matthews, and leave the reader to exercise his own judgement concerning them’.5 His Illustrations of Madness accordingly gives Matthews’s delusions the fullest possible airing, often using his own words, very likely taken down by Haslam himself, and giving a richness of detail unprecedented in the literature of madness. The result is a kind of accidental phenomenology, an insider account of Matthews’s mad-machine and machine-madness. This is apparent even in the title of Haslam’s book, which seems to slide from professional self-assurance into Matthews’s idiosyncratic style, as though Haslam’s and Matthews’s voices were performing an awkward duet. The full title is: Illustrations of Madness: Exhibiting A Singular Case of Insanity, and a No Less Remarkable Difference in Medical Opinion: Developing the Nature of Assailment, and the Manner of Working Events; With a Description of the Tortures Experienced by Bomb-Bursting, Lobster-Cracking, and Lengthening the Brain. Embellished With a Curious Plate.

Haslam explained that Matthews believed himself to be subject to violent and continuous persecution by a gang of ‘villains profoundly skilled in Pneumatic Chemistry’, who operated from a basement not far from the hospital, and assailed him by means of an apparatus called an ‘air-loom’. Haslam gives Matthews’s roster of the seven members of the gang: ‘Bill the King’, their mysterious leader; ‘Jack the Schoolmaster’, a shorthand writer who records all the gang’s doings; Sir Archy, a foul-mouthed blackguard, who is possibly a woman dressed as a man; the ‘Middle Man’, the most skilful operator of the instrument; ‘Augusta’, a 36-year-old woman, who is frequently out and about; ‘Charlotte’, apparently French, and kept a prisoner by the gang; and finally one who has no name but the ‘Glove Woman’, who keeps her arms covered because of the itch, operates the machine with skill, but has never been known to speak. Another document of Matthews, not quoted by Haslam, but included in Roy Porter’s edition of Illustrations of Madness, suggests that there may be more even than this, for he speaks of ‘[t]he dreadful gang of 13 or 14 Monster Men & Women who are so making their Efforts on Me’ (Illustrations, LXIII).

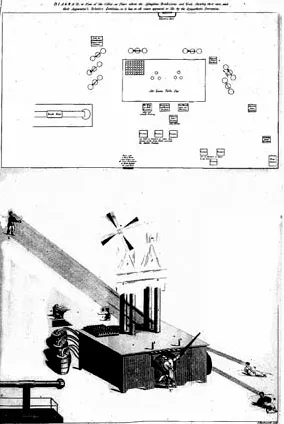

The most extraordinary feature of Haslam’s report is the drawing, by Matthews himself, which he provides of the air-loom, along with Matthews’s own detailed key to its elements. The machine seems to have worked in something like the following fashion. Noxious vapours contained in barrels are directed through pipes into the principal body of the apparatus, which is contained invisibly within an enormous desk-like structure (one of a number of features in the machine that suggests the parallels between the machine and the psychic bureaucracy that a later and still much more celebrated paranoiac, Daniel Paul Schreber, would call an Aufschreibesytem, a ‘writing-down-system’).6 As a result of some mysterious process of distillation occurring inside the machine, a magnetic-mesmeric fluid is produced, and perhaps stored in the battery-like ‘cluster of upright open tubes or cylinders, and, by the assassins, termed their musical glasses’ (Illustrations, 45). These objects may also be meant to be the magnets to which Matthews refers, and which do not seem otherwise to be visible in the illustration. It is drawn off through the tubes emerging from the apparatus and transmitted by a ‘windmill kind of sails’ (Illustrations, 45). The substance itself is described as

James Tilly Matthews’s drawing of the air-loom gang at work, from James Haslam, Illustrations of Madness (London, 1810). | |

The warp of magnetic-fluid, reaching between the person impregnated with such fluid, and the air-loom magnets to which it is prepared; which being a multiplicity of fine wires of fluid, forms the sympathy, streams of attraction, repulsion, &c. as putting the different poles of the common magnet to objects operates; and by which sympathetic warp the assailed object is affected at pleasure. (Illustrations, 48)

Edmund Cartwright had invented a power-loom that could be operated by steam or water in 1785. Matthews’s machine still appears to be lar...