![]()

PART ONE

Sensation in

Renaissance Mental

Imagery

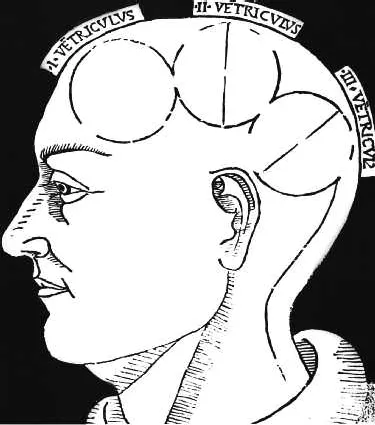

3 Anatomical cut of the head from Albertus Magnus, Philosophia pauperum (Brixen, 1490).

![]()

1

The Scientific and

Artistic Traditions

During the period ranging from the later Middle Ages to the end of the seventeenth century Europeans believed that their heads contained three ventricles (illus. 3). In these, they were told, their faculties processed, circulated and stored the sensory data by means of which they could apprehend and understand the outside world. Aristotelian philosophy served as the operating system of this hybrid construction, Galenic anatomy as the hardware and the Hippocratic theory of blood spirits and humours as the data transmitter. This system attributed a central place to images in thought processes and consequently had a considerable impact on the visual arts. The active life of this early modern account of the mind spans the period from the thirteenth to the seventeenth century. It coincides with a rise in the status and importance of images and image makers unprecedented in any other society.1

In this introductory chapter I will briefly outline the nature, properties and status of the early modern system of the mind and delineate the ways in which it has affected views about the creation, meaning and reception of early modern images.

History and configuration

In his influential treatise On the Soul Aristotle (384–322 BCE) provided a model of sensory perception and cognition, but one that placed consciousness and volition in the chest and around the heart rather than in the head. For Aristotle the brain was no more than a cooling system.2 Indeed one feature of the transition from the Ancient to the early medieval European world is the upward migration of the assumed seat of consciousness from the region of the heart to that of the brain.3 Thus a civilization localizing the self in the head succeeded to one placing the self in the chest.

By the time of the Greco-Roman physician Galen (c. 130–210 CE) the rational soul had established its quarters in the head for all centuries to come. Following the works of the Alexandrian medical school, Galen divided the brain into a set of connected ventricles where he located the rational soul.4 He asserted and imposed the idea that all the organs of the senses connect to the brain by means of nerves. It can be said of Galen that he wired sensation to reason.

While the Church Fathers accepted the Galenic model and developed a philosophy of the mind integrating several Aristotelian features,5 the full impact of Aristotle’s psychology had to wait until the twelfth century. From this period the treatise On the Soul and the Parva naturalia (sometimes referred to as the ‘Sheet Physical Treatises’) spread to the Latin West through a wave of translations which received further authority through commentaries, most notably those of Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274) and Albertus Magnus (c. 1193/1206–1280), all uninterruptedly copied, edited and printed until the seventeenth century as part of the curriculum of European universities.6 University demand prompted a steady flow of Aristotelian manuscripts and texts that by the end of the fifteenth century were augmented by humanist editions.7

Early modern Aristotelianism is a field of plurality rather than doctrinal unity – scholars now speak of Renaissance Aristotelianisms for there is little in the Aristotelian corpus that did not become the subject of dispute and controversy.8 Nevertheless, while Christian commentators experienced difficulties with Aristotle’s views on the eternity of the world and implicit belief in the mortality of the soul, they received his account of the faculties of the sensitive soul – common sense, imagination, estimation and memory – without any serious controversy and accommodated it in the already familiar Galenic anatomy of the head.9 This produced a simplified Aristotelian psychology, which eventually collapsed in the seventeenth century under the philosophical assaults of Descartes and the observations of Thomas Willis’s Anatomy of the Brain (1664).

This broad and blunt historical sketch highlights one central point: for over four hundred years Aristotle’s account of the sensitive soul was the only available cognitive model in the West. Its emphasis on images necessarily had an impact on the visual arts. We are not dealing, however, with the influence of a text over artists but rather with a phenomenon: regardless of whether every early modern European had read Aristotle, or his commentators in Greek, Latin or vernacular, all disciplines dealing with mental imagery and its depiction used the Aristotelian conception of the mind as a point of reference.

The Aristotelian mind in action

The Aristotelian mind needs sensation to apprehend the world – it would otherwise remain a tabula rasa. It does not really think through single sensations, however, but through images resulting from multiple sensory impressions. Aristotle designated this class of mental images common sensibles and hypothesized the existence of the ‘common sense’ to handle them.10 Thus from multiple sensory impressions the common sense generates images corresponding to the categories of figure, size, number, movement and rest.11 These are the constituent parts of mental imagery and the building blocks of early modern thought. The treatise On the Soul is seldom illustrated but frequently augmented with a summary invariably localizing each faculty – common sense, imagination, estimative and memory – in the ventricles of the brain.12 Thus the faculties of Aristotelian psychology are disposed in a map of the brain imposed by Galen five centuries after Aristotle.

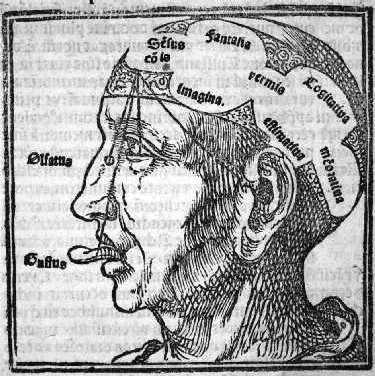

Scientific illustrations of this system frequently display lines linking the sense organs to the front ventricle traditionally housing the common sense (illus. 4). After merging into mental images this external data passes to the fantasia and imagination, which hold them for examination by the estimative powers, which modern cognitive science would associate with recognition. Such images are also the means by which the higher faculties of the rational soul acquire knowledge of the world. Once examined, inner images are stored in the memory, located in the third ventricle at the back of the head.

4 Anatomical cut of the head from Lodovico Dolce, Dialogo …nel quale si ragiona del modo di accrescere e conseruar la memoria (Venice, 1562).

Such representations appear in a wide range of publications: treatises on the soul, of course, but also popular encyclopaedias, vernacular literature, treatises on improving one’s memory.13 The variations across time of these images of the mind enhance the contrast between their stylistic variety, from amateur to professional, from medieval to Baroque, and the unity of their message conveying the very same ideas about the contents and functioning of the head.

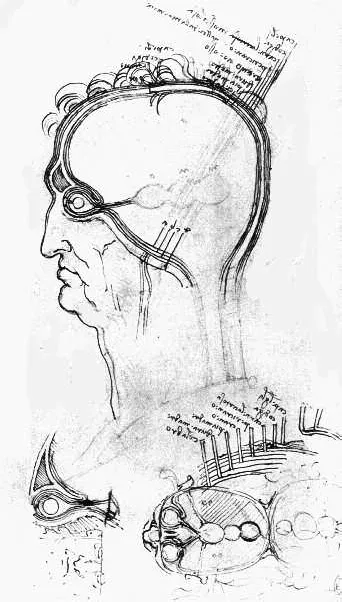

Leonardo’s version, in a drawing now at Windsor Castle (illus. 5), illustrates the overwhelming importance of this system of belief on the perception of reality. In spite of the fact that he practised anatomy himself Leonardo drew the ventricles of the brain from the side, as well as from above, as if they had really existed. In doing so he followed a mainstream tradition of scientific illustrations, as much a deeply embedded system of belief, of which the sixteenth-century physician Alessandro Benedetti provides a concise résumé in an anatomical treatise of 1543:

In these cavities are contained the faculties of the most noble senses from which is drawn the strength of reasoning, judgment and understanding; there the so-called common sense collects the species of sensitive things; there are formed the most varied images and this is where the senses of sight, hearing, smell and the other senses converge through the nerves or the membranes.14

Let us now examine the ways in which this theory affected medieval and early modern ideas on art.

Church doctrine, images and the Aristotelian soul

By tracing a path running from the outside world to the inner recesses of the soul Aristotelian philosophy provided a scientific foundation for all disciplines, religious and secular, aiming at training the mind. It is indeed no coincidence that the medieval Church, the very same institution that, after some initial hesitations, promoted the translations and commentaries of the Aristotelian corpus, happened to be the most important commissioner and consumer of images.

Before the twelfth century the Church had a theory of images in place initially enunciated by Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) and further elaborated by John of Damascus during the Byzantine iconoclastic crisis (721–843). In the twelfth century the insertion of John’s views on images into the Sententiae of Peter Lombard (1095–1160), the standard theological textbook of the Middle Ages, ensured their extensive dissemination in the West. By the twelfth century the basic doctrine of the Church had thus taken shape. It is enunciated for instance in Thomas Aquinas’ commentary on the Sententiae:

5 After Leonardo da Vinci, Anatomical Cut of the Head, c. 1490–93, pen-a...