![]()

1 Problems

The first words of Arthur Wheelock’s 1995 book on Vermeer are: ‘A “Vermeer”, like a “Rembrandt” or a “Van Gogh”, is something more than a painting.’1 Wheelock’s just observation is not simply a matter of critical rhetoric. It is a matter of perception. That matter of perception has to do with how paintings are embedded in their institutional circumstances. Perception is equally a matter of how they are entangled with their verbal descriptions, with their reproductions and with the existing knowledge and conceptions of the viewers of both the paintings and their reproductions. It is also to do with names themselves. These entanglements are the subjects of this book. Let us begin with naming.

What we describe as a Vermeer has only recently become available to us in these terms. When, in the 1860s, Vermeer’s art attracted sustained attention for the first time since his own lifetime (1632–1675) there was some doubt about his name. There are a number of other Dutch artists with similar names opening the way for confusion that persisted for decades.2 Théophile Thoré (writing as W. Burger) decided to call the artist whose revival he promoted ‘Jan van der Meer de Delft’.3 Only when archival research superseded deductive principles was ‘van der Meer de Delft’ succeeded by, first, ‘Jan Vermeer’ and, latterly, ‘Johannes Vermeer’.

John Michael Montias, who has done more than anyone else to uncover the social circumstances of Vermeer’s life and those of the members of his extended family, notes that Vermeer’s baptismal name was Joannis, a Latinized form of Jan favoured by Roman Catholics and Protestants of prominent families.4 His Christian name appears in subsequent documents as Joannes and Johannes, his surname as van der Meer and Vermeer. Vermeer himself did not use the form Jan. Montias suggested that Dutch authors dubbed him Jan to bring him closer to the mainstream of Calvinist culture, perhaps unconsciously.5 Montias deals with the documented variants in the index of his book on Vermeer by referring to him as ‘Vermeer, Jo(h)annes Reyniersz.’ (including the patronymic), but I shall follow what has only recently become standard practice, and refer to the painter as Johannes Vermeer.

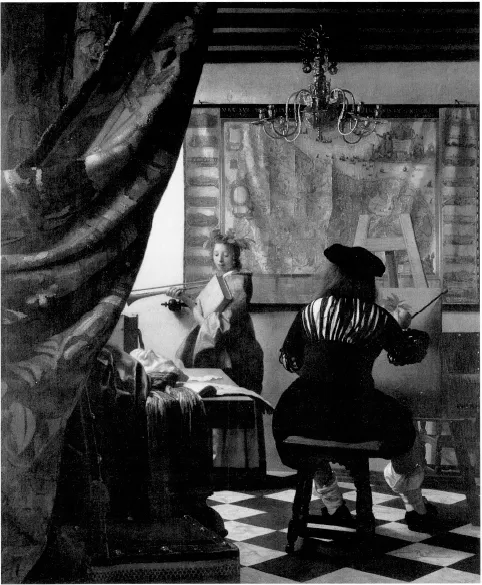

2 Vermeer, The Art of Painting, c. 1666–7, oil on canvas, 120 × 100 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

The names of paintings present different problems. Some works by Vermeer are referred to with what we take to be titles in early documents, but, even in these cases, there can be no certainty that they represent anything other than a convenient description. The only exception is The Art of Painting (illus. 2), which, as Montias has demonstrated, Vermeer’s widow, Catharina Bolnes, made great efforts to protect from her late husband’s creditors. It was described in a notarial document of February 1676, just over two months after Vermeer’s burial, as ‘a painting done by her aforementioned late husband, wherein is depicted “The Art of Painting” (“de Schilderconst”)’.6 This title has now superseded that by which the painting was long known, The Artist’s Studio. The circumstances suggest that De Schilderconst might have been how that painting was known to the painter himself.

The titles of all other paintings by Vermeer can be taken to be convenient descriptions, rather than titles in the modern sense. These descriptive titles none the less embody values and colour the way people look at the paintings to which they are applied. I have to refer to these paintings by titles (to use a museum accession number, or a catalogue raisonné number would be obfuscatory) so I have chosen to use those in the catalogue of the 1995–6 Vermeer exhibition in Washington, DC and The Hague, and the proceedings of the two symposia held on that occasion, published as Vermeer Studies.7 This is purely a matter of convenience. The sole exception is our case study.

The 1995–6 exhibition title for our case study was A Lady Standing at the Virginal.8 The title used by Neil MacLaren in his catalogue of the Dutch paintings in the National Gallery, London was A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, and this was retained by his successor, Christopher Brown.9 To make a social judgement about the person in the painting in its title seems pointless, so I reject ‘Lady’; further, I see no point in making a judgement regarding her relative age, so drop ‘Young’. I am left with the title that I use throughout this book, the Woman Standing at a Virginal. I set no great store by it. Like the other painting titles, it is no more than a convenience.

Before we turn to the problem of ‘Vermeerness’ and the mystique that surrounds it, it would be prudent to discuss some of the boundaries within which the entire enquiry will be conducted. These concern, first, what we might claim to know about artists through their work; secondly, the nature of the visually apprehensible object – the work of art – and by what means we might most conveniently analyse it; and, thirdly, the limitations and opportunities that these conditions suggest.

A tacit assumption behind much writing about art is that our purpose is to know the artist’s intentions and, thereby, the artist’s psyche. Can we know artists through their work? Richard Wollheim has addressed this issue in a highly sophisticated manner in his study Painting as an Art.10 I confess to being less optimistic than Wollheim about the possibility of knowing artists through their work. Even if this were possible, is it desirable? To risk a general observation, artists seem to be desperately remote from the art they make in the perception of those who apprehend that art. However, that distance – that unreliability of visual art as a tool of subtle or unambiguous personal communication – does not seem to vitiate the making of art as a project.

Although an oversimplification, we might consider in these circumstances art to be primarily artefactual rather than communicative. This is not to say that one cannot communicate visually; yet, generally speaking, the further towards the putative condition of art an object may be, the more idiosyncratic, obscure and subject to misunderstanding is its intentional communicative element. The use of language, too, can be more or less clear; though, when the visual and the linguistic are compared, we might (with various heavy caveats) claim more reliable knowledge of someone through what they write than through what they paint (sculpt, etch, photograph, etc.).

Writing can (though of course need not) convey information as unambiguously as human contrivance can allow. Visual sign making can convey information to a limited extent (hence the use of such signs to convey simple information where any given written language may not be comprehensible to all or to many people, as at airports). Writing can convey ideas equally unambiguously (though, once again, need not). Visual sign making can convey ideas unambiguously only at a remove. For instance, by painting a representation I do not thereby reliably convey a set of ideas about what is represented, though by means of shared visual conventions a viewer might justifiably infer ideas about choices among the protocols of representation available to me. To convey abstract ideas I must deploy representations within secondary systems of conventions that must be learned: conventions concerning physical expression (for example, those codified by Charles Le Brun) and personification (such as those codified by Cesare Ripa). This is not to say that instances of visual representation are themselves in any sense transparent or natural. It seems more prudent, if less convenient, to treat as a cultural skill, rather than as an innate propensity, the ability to recognize, say, a tree in the contrived likeness of a tree, irrespective of whether or not this is actually the case. I suspect, though, that in the culture to which I belong (the Euro-American hegemony) mimesis, in the sense of an operative effect of transparency, and semiosis, in the sense of an awareness of shared conventions allowing sign recognition, are interdependent in any depiction.

Mimesis cannot usefully be reduced to the terms of semiosis, though there are those who insist upon it. They argue that the linguistic mode of analysis is indeed appropriate for discussion of all visually apprehensible, purposefully constituted objects, because any indexical characteristics (in C. S. Peirce’s sense of the term, to denote a direct or motivated link between representation and referent)11 are necessarily conventional. As Umberto Eco has put it:

Everything which in images appears to us still as analogical, continuous, non-concrete, motivated, natural, and therefore ‘irrational’, is simply something which, in our present state of knowledge and operational capacities, we have not yet succeeded in reducing to the discrete, the digital, the purely differential.12

Whether or not Eco’s assertion, based on what Peter Wollen characterized as ‘a thoroughgoing binarism’ in which the brain is conceived of as a computer,13 is in the end accurate seems pragmatically beside the point. Its effect is Ptolemaic, for it anticipates ever more complex constructions within an existing paradigm to account for what might be described more persuasively by other means.

The description, let alone the explanation, of effects peculiar to the laying on and apprehension of glazes in oil paintings, or pietra dura, or veneers in intarsia, are not in practice conveniently reducible in their entirety to linguistic or even more generally semiotic terms. In questions of representation (or the creation and apprehension of likenesses) – itself a subset of objects of visual interest, but one which some commentators erroneously assume comprehends all art worth discussing – the concept of mimesis is worth reconsidering as a possible explanatory tool, though as a complement to semiosis.

The consequence of these observations, for now, is that, in spite of the generative capacity of conventional iconography, accurate denotative abstraction is not directly available to the visual artist. Thus while I can write unambiguously and directly T am lonely’, even with the most eloquent self-portraiture (or other visual representation) I cannot achieve the same in paint (or any other visual medium). The best I can hope for is the viewer’s reaction ‘He looks lonely’, or ‘He must be lonely.’ This is an inference. The viewer’s share in constituting meaning in a painting can profitably be thought of as different not only in degree, but in kind from the reader’s share in constituting meaning in a text, so different from each other are the systems of signification.

There is a tendency in some recent writing about art to discuss objects of visual interest as texts. The justification stems from the application to the visual of linguistically focused semiotics. Semiotics can add much to the discussion of such objects, but language based entirely upon convention is but one subset of semiotics. Attention to this subset, predominantly by French and French-inspired theorists dominated by – as Martin Jay has demonstrated – a distrust of the visual,14 has led to the subsumption of the entire field in its terms. Some commentators use the term text of an object of visual interest to signal a concern with it as a site of work, of contestation, of contingent constitution on the part of its beholders and users, as a fluctuating nexus. Thus it is to be distinguished from the object perceived as principally materially bounded, self-contained, essential, aesthetically constituted, passive and unchanging. While I have sympathy with the aim, to assign the term text to such objects is to swamp the visual with the linguistic. It is a form of catachresis, that is, ‘the application of a term to a thing which it does not properly denote’, in the words of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. As such, it is inhibiting rather than liberating, and indicates an unwillingness, or even an inability, to conceive and articulate in terms specific to the material.

Some would argue that the subsumption is not purely rhetorical, but describes a state of affairs in which all human-made visually apprehensible marks do indeed constitute writing in a linguistic sense. Writing and object-making can indeed coalesce as somatic traces amenable to sexual, cultural and class differentiation – and have done from the Book of Kells to Mary Kelly. Yet the exclusive application of formulations developed to account for the linguistic to objects would seem to be as limiting as to discuss language predominantly in terms that we might aptly apply to such objects.

Many now think of the complex pictorial sign (which concerns us) as being made up of arbitrarily defined signifiers (which most resemble texts in their use), and indexical signifiers (in which recognition of any arbitrariness of composition is discouraged). The longevity of this conception is indebted, in part, to the considerable influence of the work of Jacques Derrida. Although Derrida is not uncritical of Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistics, the latter’s conception underlies much of his own work.15 Arguments have been advanced, notably by J. Claude Evans, that suggest serious flaws both in Saussure and, by transmission, in Derrida.16 This is especially signif...