![]()

ONE

INTERNALIZING RUINS:

Premodern Sensibilities of Time Passed

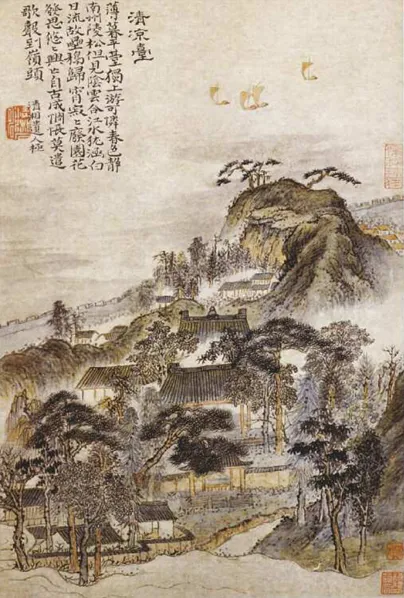

1 Shitao, Qingliang Terrace, hanging scroll, c. 1700, ink and colour on paper.

Where are the Ruins in Traditional Chinese Art?

Several years ago, after re-reading writings by Hans Frankel and Stephen Owen on the Chinese poetic genre huaigu – ‘lamenting the past’ or ‘meditating on the past’1 – I decided to conduct a survey of ruin images in Chinese painting because such images frequently appear in huaigu poems. The result surprised me: among all the examples I have checked, covering a broad chronological span from the fifth century BC to the mid-nineteenth century AD, only five or six depict ruined buildings.2 Typically, the architectural structures in a painting show no trace of damage, even if the artist has inscribed a poem next to the image describing their ‘broken roofs’ and ‘ruined entrenchment’ (illus. 1). I was no less astonished when I turned to architecture: there was not a single case in pre-twentieth-century China in which the ruined appearance of an old building was purposefully preserved to evoke what Alois Riegl has theorized in the West as the ‘age value’ of a manufactured form.3 Many ancient timber structures do exist, but most of them have been repeatedly renovated or even completely rebuilt (illus. 2). Each renovation and restoration aims to bring the building back to its original brilliance, while freely incorporating current architectural and decorative elements.

Although I could simply have continued my search for images of ruins, these initial findings were forceful enough to prompt me to ponder their implications. Logically, I questioned first why I was so surprised by such findings: clearly I, like many other people as I found out later, had presumed that ruins were an integral element of traditional Chinese culture and existed in both architectural and pictorial forms. It is also clear that in making such a presumption I was unconsciously following a cultural/artistic convention that is at odds with the traditional Chinese ways of representing ruins – if such representations indeed existed in art. This realization led to two kinds of reflection, about the origin of such a misconception and about indigenous Chinese concepts and representational modes of ruins.

A contemporary observer has been exposed to various cultural influences, which could have shaped his imagination of ruins in traditional China. The most powerful influence comes from the Romantic view of ruins, which, Paul Zucker argues, still determines today’s popular approach to ruins.4 This view has a long genealogy in European art and architecture: ruins were depicted in paintings before the Renaissance and entered garden architecture in the sixteenth century. But it was not until the eighteenth century that sentiment toward ruins penetrated every cultural realm (illus. 3, 4):

| 2 Temple of Heaven, Beijing, built 1406–20. |

They were sung by Gray, described by Gibbon, painted by Wilson, Lambert, Turner, Girtin and scores of others; they adorned the sweeps and the concave slopes of gardens designed by Kent and Brown; they inspired hermits; they fired the zeal of antiquarians; they graced the pages of hundreds of sketchbooks and provided a suitable background to the portraits of many virtuosi.5

It was this tradition that led Riegl to write his theoretical meditation on the ‘modern cult of ruins’ at the turn of the twentieth century.6 Around the same time, this European tradition also became global, as non-European writers, painters and intellectuals embraced literary and artistic Romanticism and disseminated it in their native countries. In China, as I will recount in chapter Two, ruins became an important painting subject in the early twentieth century; the Picturesque style and sentimental appeal of these images unmistakably reveal their origin (see illus. 76–8, 84, 111).

Although numerous books and essays have been written on the creation of artificial ruins in European gardens of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the relationship between these structures and another type of architectural folly – fanciful imitations of Oriental buildings (illus. 5) – seems to have eluded most discussions. An obvious reason for this oversight is their marked differences in function and appearance: whereas sham Greek or Roman ruins evoked historical memory and melancholic rumination with their solemn and dignified forms, the Oriental follies were exotic ‘eye-catchers’ that conveyed, in Horace Walpole’s words, ‘a whimsical air of novelty’.7 I would suggest, however, that the repeated juxtaposition of these two contemporary architectural types points to a deeper concept in Romantic art, in which the Picturesque and exotic, indigenous and foreign, nature and artifice, contribute to a mixture of beauty and the Sublime in an imaginary visual world. The juxtaposition of the two types of follies is found not only in actual gardens but also in design books, trompe l’oeil murals, decorative patterns (illus. 6) and theoretical discourses. In writing and speech, Chinese gardens were evoked to justify the Romantic dissatisfaction with formal gardens.8 The association between the Picturesque and the exotic also explains why some painters depicted Chinese buildings in the manner of classical ruins. An early example of such cultural coalescence, an engraving made in 1626 by Velentin Sezenius (b. 1602), shows a group of buildings, consisting of a half-broken bridge and a dilapidated watermill amid Oriental figures, willow trees and a phoenix (illus. 7).

3 Antonio Canaletto, Rome: Ruins of the Forum, Looking towards the Capitol, 1742, oil on canvas. | |

4 The water reservoir of 1748 at the Ruinenberg, Potsdam.

5 Chinese Tea House in Sanssouci Park, Potsdam, designed by Johann Gottfried Büring, 1755–64.

| 6 Carved and painted 18th-century Chinoiserie panels, originally in the Hôtel de la Lariboisière, Paris. |

Among the eighteenth-century European architects who pursued Oriental follies, none was more diligent or influential than William Chambers (1723– 1796), the official architect of Princess Augusta and the architectural tutor of her son, the future George III.9 Significantly, the effort he made to simulate Chinese architecture in English gardens was closely related to his commitment to constructing classical ruins in the same settings.10 His design for Kew Gardens, near London, typifies this parallel interest: the ornamental follies he built there included, among others, a ruined Roman arch (illus. 8), a ten-storey Chinese pagoda (illus. 9), a ‘menagerie pavilion’ in a typical Chinoiserie style, and a relocated House of Confucius. Going a step further, he wrote in his 1772 Dissertation on Oriental Gardening that the Chinese actually decorated their gardens with decaying buildings, ruined castles, palaces and temples, half-buried triumphal arches, and ‘whatever else may serve to indicate the debility, the disappointments and the dissolution of humanity; which . . . fill the mind with melancholy and incline it to serious reflection’.11

One wonders on what basis Chambers made this claim: although he did visit Canton twice in the 1740s, his account about the artificial Chinese ruins contains little truth.12 It is possible that at the time he, a young employee in the Swedish East India Company, had not yet received any of the professional training that later made him a renowned architect, and so mistook some broken-down buildings as deliberate aesthetic objects.13 It is also possible that he, as his biographer John Harris says, put his ideas ‘into the mouths of the Chinese’14 to support his own theory. As we have seen, this had become a conventional rhetorical strategy by the time. Chambers probably never really fashioned a Chinese-style ruin; but such a project would not have been impossible: a ruined bridge he designed in 1762 for Thomas Brand’s estate The Hoo, near Hitchin, has noticeable affinities with a Chinese bridge he proposed for Frederick II’s New Palace at Sanssouci. We can also trace both designs back to Sezenius’s engraving (see above), in which a ruined bridge defines the visual centre.

7 Velentin Sezenius, Chinoiserie design, 1626.

8 William Chambers, ruined Roman arch, Kew Gardens, 1759.

Part of Chambers’s extravagant description of Chinese gardens was questioned by his contemporaries. Supported by popular lore and images, however, his account of the Chinese taste for ruins seems to have been more willingly accepted. So even in 1967, Rose Macaulay, a British novelist and the author of Pleasure of Ruins, still cited him to suggest that ‘The Chinese . . . seem on the whole to have always taken a view of ruins both more tranquil and more sad.’15 Macaulay, on the other hand, also drew evidence from a more authentic source – traditional Chinese poetry on ruins whose English translations became available after Chambers’s day. She quoted, for example, the 1918 translation by Arthur Waley (1889–1966) of Cao Zhi’s (182–232) lamentation on war-ruined Luoyang:

In Luoyang how still it is!

Palaces and houses all burnt to ashes.

Walls and fences all broken and gaping,

Thorns and brambles shooting up to the sky.

How sad and ugly the empty moors are!

A thousand miles without the smoke of a chimney.

I think of the house I lived in all those years:

I am heart-tied and cannot speak.16

9 William Chambers, Chinese pagoda in Kew Gardens, 1762.

By quoting this and similar poems, Macaulay shifts her focus from ruins as a type of garden architecture to ruins as poetic stimulus and imagery, which defines the poetic genre huaigu. To my knowledge, a comprehensive history of huaigu has not been attempted; but this history must at least comprise four crucial phases: the emergence of the poetic sensibility of huaigu during the Han (206 BC–AD 220),17 the formation of the poetic genre huaigu during the Wei-Jin period (220–420),18 the popularity of huaigu poems during the Tang (618–907),19 and the continuing imitation and proliferation of huaigu poems throughout later periods. The significance of huaigu poetry is not limited to literature because it typifies a general aesthetic experience: looking at (or thinking about) a ruined city, an abandoned palace, or a silent ‘void’ left by historical erasure, one feels that one is confronting the past, both intimately linked with it and hopelessly separated from it. Huaigu sentiment is therefore necessarily stimulated by historical traces and erasure, and is defined by an introspective gaze, a gap of time, effacement and memory. ‘The master figure there is synecdoche,’ writes Stephen Owen, ‘the part that leads to the whole, some enduring...