![]()

part one

History and

Contemporaneity

![]()

two

From Geography to Topography

Let’s begin with two seemingly naive questions: does Central Europe (still) exist and does it (still) have anything significant to say? These questions posed in such a way already contain their answers. If we are asking whether Central Europe has anything to say, we have to assume that it (still) exists. This is not the place for tracking historic processes that shaped modern Central Europe. However, it is important to note that even if this term was not widely used during the period of Soviet domination, at least not within art criticism, nonetheless a sense of distinctness was felt in this part of the European continent. When communism collapsed, the question of whether Central Europe exists began to be raised, or more precisely, a considerable number of artists, critics and curators began to question the usefulness of such geographic framing of art. If the old system was gone and a number of the post-communist countries has been incorporated into the (Western) European structures, while others, to a greater or lesser extent, aspired to do so in the future, if in the new post-1989 reality the world (or at least Europe) became more free, if the borders have been opened (including the new ones that were just created), then why should we maintain such an anachronistic geographic frame? These are not isolated voices. Maria Hlavajova, a Dutch curator with a Slovak background, is certainly one of them. Hlavajova does not see any need for maintaining such a geographic construction after the collapse of the Iron Curtain. On the contrary, she believes that there is a real opportunity for free competition among artists working across borders and creating artistic culture without boundaries. Moreover, she notes that there are quite a few ‘really good’ artists and curators from the former Eastern Bloc who have done very well for themselves in the West and for whom the old divisions are meaningless. Also, there is a movement in the opposite direction. Increasingly, Western artists and curators are showing interested in the post-communist countries, not as exotic localities, but as potential partners.1 As mentioned earlier, this is not an isolated reaction. However, it can certainly be seen as a reaction against the old atmosphere of communist claustrophobia, closed borders, control of the artistic culture and repression. It can also be seen as a response to being condemned to provincialism and to being de facto seen as a second-class European culture. This was a response to the calls for a return to ‘normal’ existence, whatever that was supposed to mean, after the fall of the Berlin Wall.2

There are also, of course, other opinions. Marina Gržnić provides one of the most interesting. Reaching for psychoanalytic terminology, she defines Central (or rather Eastern) Europe, in the wake of fulfilment of its historic mission, as Europe’s ‘surplus’ and, simultaneously, as ‘insufficient’ Europe. This formulation echoes Jacques Lacan’s Oedipal definition of the human being as someone who has already fulfilled his destiny. To diagnose this condition, Lacan uses the term ‘plus d’homme’, which simultaneously signifies excess and lack of humanity. This part of Europe can be compared, therefore, to excrement, which has, however, a crucial function. The subject (Europe) cannot construct its own identity without such excrement, just as a human subject needs its own ‘waste’ to create his own identity.3

Igor Zabel approaches the problem of the East-West from a different perspective, using different vocabulary. In his essay ‘The (Former) East and its Identity’, the author argues that while the fall of communism, and hence the end of the world’s division into two opposed blocks, certainly opened the (former) Eastern Europe, it did not eliminate differences that have divided the continent.4 They are still visible within the cultural infrastructure and can be seen in the characteristic underdevelopment of the institutional system, critical discourse and analytic vocabulary that allows the West to (still) function as the guarantor of values. It is (still), but not exclusively, the West that creates and controls the system of concepts and the hierarchy of institutions. However, the issue of the difference between the West and the (former) East, or post-communist Europe, has much deeper roots. One could say that it has its origins in the desire for diversity that is a feature of the postmodern worldview. If modernism strove for unification and universalization of culture, then postmodernism feeds on diversity. It is difference that functions as the foundation of identity. In effect, it is the West that is interested in maintaining the tension between itself and the East, or between the Self (the West) and the Other (the former East), since this tension allows it to identify its own position and to construct its own identity. It appears, therefore, that Zabel’s conclusions, arrived at by the use of a very different analytic apparatus, are rather similar to those of Marina Gržnić: it is the West that needs the East (including those parts of Central Europe that belonged to the former Eastern Europe) in order to define itself, and not the other way around.

Irrespective of the ongoing discussions about the existence or nonexistence of Central Europe after the fall of communism, the bonds that hold contemporary Central Europe together have been forged by history or, to be more precise, by political history. Although this history is rather varied, nevertheless it creates a point of reference for contemporaneity. That is, of course, if one assumes that history could perform such a function for the present, which is far from certain. The concept of ‘post-communist’ Europe as such contains a chronological element; it describes a temporal sequence, something that followed a particular historic experience (of communism). I think that even though communism ended more than twenty years ago, history and historic or art historic memory can still provide effective frames of reference for the analysis of contemporary political and historic processes.

Such an interpretative frame for art historic analysis has two mutually attracting poles that mark the common denominator or a shared point of reference for the post-1989 culture in Eastern Europe. One is the idea of the autonomy of art, the other a critique of the system. The first concept, compatible with the modernist system of values, was not at all apolitical. On the contrary, if official art, or more precisely Socialist Realism, which endured in many countries of the region for a long time, was perceived as political propaganda, even when it did not carry explicit political messages, then the search for artistic autonomy and rejection of ‘political engagement’, or more precisely of political propaganda, could not be apolitical. That is how artists and dissident intellectuals perceived the notion of artistic autonomy. One of the most common attitudes of the post-Stalinist artistic culture was the flight from the official aesthetic doctrines in the direction of autonomy, the embrace of personal expression and individual creative freedom. On the other hand, the number of those who were engaging in a more or less direct critique of the political system was much smaller. Their critique did not necessarily challenge the system of power itself, but rather was directed against its supporting mach in ery, institutions and discourses. This type of art, mainly growing out of the neo-avant garde practice, developed at different pace in different countries. In the 1960s in Czechoslovakia there were Prague-based ‘actionists’, such as Milan Knižak and Eugen Brikcius. The ‘happsoc’ group (Stano Filko, Alex Mlynarčik and for a short period the art historian Zita Kostrová) and Július Koller were active at approximately the same time in Slovakia. In Poland there were artists associated with the Gallery Repassage in Warsaw and later grouped around Józef Robakowski in Łódź. Hungary produced the most political artists in the Eastern Bloc, who engaged in a direct critique of the system, especially around 1968 in response to the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the armies of the Warsaw Pact. They included László Lakner, Tamás Szentjóby, and somewhat later Gyula Pauer and Endre Tót. In East Germany there was Robert Rehfeldt. Those neo-avant garde critics of the system and the modernist proponents of artistic autonomy shared a subversive attitude. It was this variously expressed opposition to the communist system that functioned as the basis of the artistic culture of Central Europe and represented its most significant contribu tion to the culture of those times. Today, however, one must inquire whether such an attitude could provide a sufficient basis for the production of art in the post-communist era? In other words, can such art revise its own subversive tradition under the post-communist conditions?

It is tempting to answer in the affirmative, but unfortunately such a response could not be unequivocal. As we know from experience, the fall of communism ushered in a period of vigorous growth of the art market. And market-based subversion of the type one could see in post-perestroika Russia had very little to do with actual critique. The Soviet symbols, which were used critically by the art of the 1980s, turned in the following decade into mere commercial devices produced to satisfy growing market demand. Such commercialization of the perestroika culture characterized the collapse of the critical attitude most closely associated with Moscow conceptualism and the Soc-Art movement. According to Joseph Bakshtein, the nonconformist trad ition provided contemporary Russian art with a significant historic point of reference. It remains an open question how younger Russian artists will use that tradition.5 In Central Europe similar processes took on different forms, mainly based in late neo-expressionism. But it is clear, that the power and attraction of the art market significantly diminished any interest in critical and political art in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. Jana and Jiři Ševčik christened this phenomenon ‘new conservatism’ in the Czech context.6 In Poland, wrenched by ideological conflicts surrounding the role of religion and the authoritarian position of the Catholic Church in Polish society, there was a different situation. However, it is important to note that despite such negative influences of market capitalism on the art scene, there have been many artists interested in commenting on the transformation of the system and later on the entrenchment of the new system of power.

Three different artworks, each with a different critical and metaphoric resonance, all providing commentary on the historic date of 1989, serve as good examples of such ongoing interest. They are Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Leninplatz-Projection, 1990, David Černý’s Pink Tank, 1991, and Tamás Szentjóby’s The Spirit of the Monument to Freedom, 1992. Each work took the form of an intervention in a public space and each referred to the transition from the just concluded past to the just beginning future. The embrace of the public space is extremely important in this context, since the access to public space was until recently strictly limited, controlled and for the most part completely unavailable to artists. The change in the political system brought a fundamental change in the status of public space. After all, democracy requires and is supposed to guarantee everyone free access to public space. Of course, this provision has been a subject of wide-ranging theoretical debate. From the perspective of ‘deliberalizing democracy’ (Jürgen Habermas), public space is subject to consensus, whereas critics of liberalism and proponents of radical or ‘agonistic’ democracy (Chantal Mouffe) see public space as the place of continual, endless resistance that guarantees democracy. Its preservation prevents the possibility of exclusion from the agora. Rosalyn Deutsche, drawing to a significant extent on the work of critics of liberalism (Chantal Mouffe, Ernesto Laclau, Claude Lefort and Étienne Balibar), believes that continual problematizing of the public space is necessary for democracy.7 Of course, before 1989, and even now, the development of democracy has encountered many difficulties in post-communist countries. This precisely makes artists’ participation in the debate concerning public space so important. After all, their frequently controversial projects provoke public debate without which democracy withers. It is such debate, which reveals deeply seated conflicts and allows for the airing of opposing views, rather than the building of consensus, that by definition eliminates and excludes radical voices from the public sphere; it is debate that creates the necessary conditions for the development of a democratic society. The art projects I mentioned earlier were some of the first manifestations of such a use of public space in post-communist Europe, and constituted, therefore, some of the first steps towards democracy.

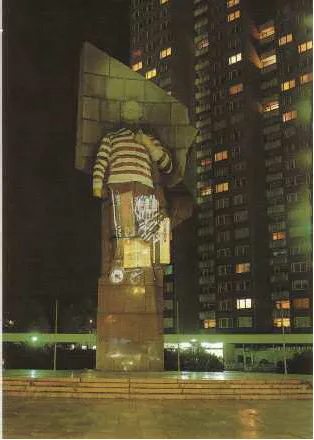

The earliest of those works, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Leninplatz-Projection, 1990, created in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Die Endlichkeit der Freiheit’, which took place at various sites throughout Berlin, used the monument to Lenin located on Lenin Square in the former East Berlin.8 The artist projected onto Lenin’s figure an image of an Eastern European consumer, dressed in a striped shirt and holding a cart filled with different consumer goods. It is clear that this image was referring to the invasion of the West by the citizens of the former Eastern Bloc, who came to buy such as electronic goods, Western groceries and clothes. The fall of the Berlin Wall and opening of the borders was initially associated primarily with access to such consumer goods and it was precisely this association that drew Wodiczko’s attention. This was one of the most characteristic aspects of the ‘autumn of nations’. This phenomenon, so often ignored and concealed by politicians and intellectuals, in fact defined the character of the first contact between the East and the West right after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

| 8 Krzysztof Wodiczko, Leninplatz-Projection, Berlin, 1990. |

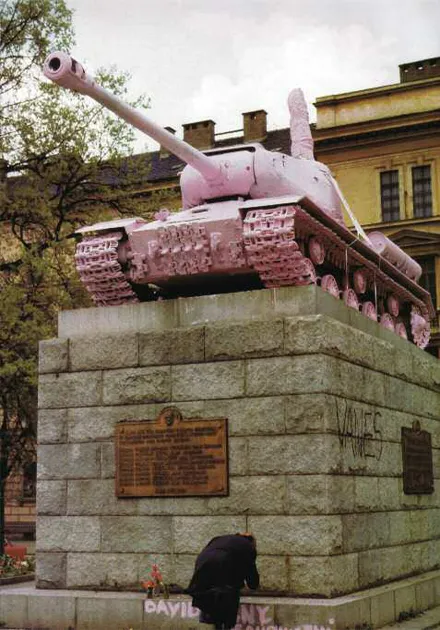

The next project, David Černý’s Pink Tank, 1991, referred to completely different values. The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia did not inspire iconoclastic gestures, at least not at the time. A tank used as a monument symbolized (not only in Czechoslovakia) the Soviet Union’s ‘liberation’ of the region from Nazi occupation. During the ‘liberation’ of 1989 and for some time afterwards, the tank, which in this context signified the oppression of the Soviet Union, remained as if nothing much happened. Černý decided to domesticate, tame and adopt it, thereby stripping it of its former symbolic function and giving it a new one, much more appropriate to the mood of the moment. In the spirit of Dadaism, the artist aided by a group of accomplices tested the nature of the transformations taking place by painting the tank pink, a colour that had nothing to do with militarism, and adding an appendage to its cupola in a shape of a finger, which allowed the tank to make a rather rude gesture. Those actions were certainly successful in provoking a response. The conflict they engendered, so necessary for the emergence of the public space and the development of democracy, revealed interesting tensions within contemporary Czechoslovak society. In addition to being applauded and supported, Černý’s action was also criticized and condemned as an act of vandalism, revealing that mental and cultural transformations did not necessarily follow political ones. A considerable part of society, despite the traumatic experience of 1968 when tanks with Soviet stars were associated with aggression, was simply unwilling to accept the symbolic annihilation of its own history. This negative response demonstrated that the official history of the CSSR was not just an ideological discourse of power, but was in fact accepted as true by a large numbers of Czechs.

9 David Černy, Pink Tank, Prague, 1991.

The third work, Támas Szentjóby’s The Spirit of the Monument to Freedom, 1992, likewise involved subversive appropriation of the existing communist-era monument. Szentjóby covered the figure overlooking Buda pest from Gellért Hill with a massive tarpaulin with two cut openings for eyes, which recalled popular representations of ghosts. In contrast to the reaction in Prague to Černý’s guerrilla action, the transformation of the Soviet era monument into a ghost, which took place in conjunction with an official ‘Festival of Farewell’ organized by the city’s government to commemorate the first anniversary of the departure of the Red Army, did not provoke controversy and was greeted with general approval. The artist certainly fulfilled the expectations of Hungarian society by transforming a historic symbol of the former Hungarian People’s Republic, a country marred by horror, terror, repression and functioning under the watchful eye of the Soviet Red Army, into a ghost of history, a phantom that can provoke fear, but, like every ghost, more in nightmares then in reality.

All three of those projects used existing monuments linked with the old regime to inscribe them with social and political changes taking place. As such they were engaging in the discourse of historic revisionism; they looked at the past from the post-communist position, but also directed their gaze at the future. Addressed to the local viewer, they confronted experienced and known contemporary reality with historic memory provoking critical reflection on the relationship between the past and the future. Slovak artist Roman Ondák produced a similar work in 2001 in Vienna, this time, however, situating his intervention in the international public space, that is in the sphere of contacts among neighbouring nations: those from the East (often perceived as economically less advanced and not quite equal partners) and those from the West. In the work entitled SK Parking, 2001, Ondák parked several Škodas with Slovak licence plates for two months on the car park of the Vienna Secession. Although the cars were not identified as a ‘work of art’, they eventually began attracting the attention of passers-by and especially of the gallery’s visitors.9 Škodas with Slovak licence plates were not uncommon in Vienna after 1989. On the contrary, since Slovakia was within easy driving distance, they became a common sight. Whether they were welcomed, that’s a different question. Leaving aside the issue of air pollution by these much less environmentally friendly Eastern European cars, their presence on the well-ordered streets of Vienna functioned as a symbol of the not always welcomed presence of the ‘close’ Other and drew attention to the proximity of the East, as well as to the open border and the influx of a cheap, mostly illegal workforce. Parking several such cars for a prolonged period in front of an architecturall...