![]()

I

THE CASE FOR

DISRUPTION

THE BAROQUE IS SET APART from what precedes it by an interest in movement above all, movement which is a frank exhibition of energy and escape from classical restraint. The psychological and social meanings of such disruptive impulses are diverse but it is obvious from the start that the style is not just a formal exercise but signals a transformation of human consciousness. In fact the Baroque is one of the necessary ancestors of Romanticism. This is not to say that this mode is primarily interesting for what it leads to, but rather that the Baroque is no dead end or herald of spiritual exhaustion.

The Baroque desire to suggest movement in static works of art meets its severest challenge in architecture. Baroque buildings have never ceased to annoy purists because they strive after the impossible, aiming to suggest to viewers that they are watching an unfolding process rather than a fixed and finished composition. Such effects are hardest to obtain on very large scales but this does not deter an overweening Baroque artist like Bernini. He has shaped the empty space in front of St Peter’s into the archetypal Baroque work, which although the masses of colossal Tuscan columns in rows four deep are enormous, remains more empty than full, a sketch of something even grander, a great oval room that upstages as well as introducing the building which lies at its far end. Bernini also had plans to provide such a setting for his favourite classical monument, the Pantheon. For him, it was a way of extending the building’s aura into its surroundings, and thus enlarging the effect of architecture.

He likened the two arms to the embrace of a protective female, the Church, which shows that he anticipated a subjective reading. The arms are not a cool display of classical proprieties but an impinging appeal, a large gesture which sweeps the spectator along in its wake. Like other Baroque artists, Bernini saw the physical materials of art as means of working on spectators’ emotions, a headlong pursuit which can seem vulgar or unscrupulous to modern eyes.

The oval plan is often met in the Baroque and this is not the only time Bernini employs it crosswise, with the short dimension used as the axis of entry. But of course one of the beauties of urban squares in contradistinction to buildings is their porousness to entry from different sides. Only in Mussolini’s time did Bernini’s Piazza acquire the appearance of a single way in, when he drove the via della Conciliazione through from the river to a point opposite the church façade: in planning terms not a conciliatory gesture – Bernini meant the oval to burst upon the visitor emerging from narrow surrounding streets, not announce itself from a mile away. The effect he wanted can still be approximated by coming at the oval from the side rather than the front. In this way the Colonnade is met as an obstacle thrown across the street, on a different, triumphal scale and slippery in its unwonted curve. Once inside, you watch the space expand around you, its ‘walls’ individualized by the columns into something like a promenading throng.

Bernini and Borromini, the two great architects of the Roman Baroque, are antithetical figures. At St Peter’s Bernini worked with huge spaces and lavish budgets, a master of extravagance. Borromini by contrast is a master of parsimony who obtained some of his best effects in moulded plaster, which he preferred not to dress up in colour and gilt, disguises obscuring the essential forms.

But if Borromini is severe, at the same time he is disturbingly licentious, taking unequalled liberties with classical system. He seems to thrive in awkward situations, cramming monumental façades into narrow streets. Like Bernini orchestrating his vast plain, Borromini also aims at dramatic effects of movement, through compression not expansion. One of his earliest works is an optical joke in the form of a little passage leading off a courtyard in a nobleman’s palace, the Palazzo Spada in Rome. Borromini’s corridor is lined with columns and closed by a statue in the open air at the far end. The trick is that the space between us and the statue is illusory. The columns shrink precipitately and thus conceal the fact that the distance is shorter and the statue much smaller than we suppose. Lured into the passage, we find ourselves ducking, as walls and ceiling close in.

For the rest of his career Borromini went on repeating this joke in subtler forms, creating false recessions in his façades and interiors, which multiply, and you could say theorize, the space we are looking at. One of the goals of Borromini’s departures from classical norms must always have been to make the user think, but for anyone who enters into the experience, his architecture is powerfully visceral as well.

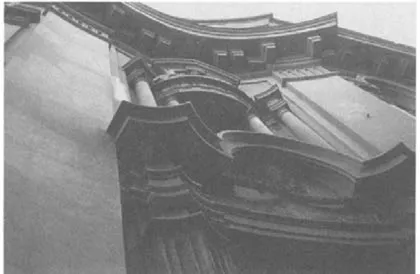

Probably his least known major work is the Collegio di Propaganda Fide (illus. 1) in an unimportant street near the Piazza di Spagna. Here he had the pleasure of demolishing an earlier chapel by Bernini to make a larger church. Bernini’s was a slippery oval and so Borromini’s replacement is a staid rectangle. But interior and exterior are disjunct: on the street Borromini executes one of the great Baroque tours de force, imparting a sensation of violent movement to what is underneath it all a flat façade. He does this by tricks not far from those of theatrical scenery, hollowing out the wall a little and then exaggerating this concavity with a gigantic protruding cornice which follows the curve. Under the cornice is a series of seven niches, each containing a large window, but each also acting as a little architectural stage, developing steep receding space in its own ingenious way.

Taken altogether and seen from underneath the whole thing can cause a mild vertigo or at least make you think you are seeing things, as sizes and distances melt and change before your eyes, jutting ledges leading straight on to others you know to be far above them or breaking off and leading nowhere. As a spatial landscape the façade is phantasmagoric, echoing the unexpected clumping and disjoining of events in dreams. And yet every detail is hard edged, and every distortion of classical normality is measurable.

1 Francesco Borromini, Collegio di Propaganda Fide, Rome, 1647–65.

One could link instability and contradiction in Borromini’s forms to general spiritual crisis in the seventeenth century, or one could say that the Baroque preference for dynamic effects corresponded nearly with Borromini’s restless temperament. He remains a striking case of someone working in a traditional vocabulary and manipulating imagery he does not invent, who nonetheless produces results which seem to issue from the deepest recesses of his personality.

What began by seeming a limitation of the architect’s power, the narrow space available for experiencing his work, is converted at Propaganda Fide to a spur to mental and visual investigation. Two-dimensional forms like paintings do not usually permit varied angles of approach as buildings do. Except for anamorphic freaks, which work only from the side not head on, more exciting in a long corridor (as at Trinità del Monte) than in a cabinet, no one to speak of before Monet had exploited the spectator’s mobility in front of pictures.

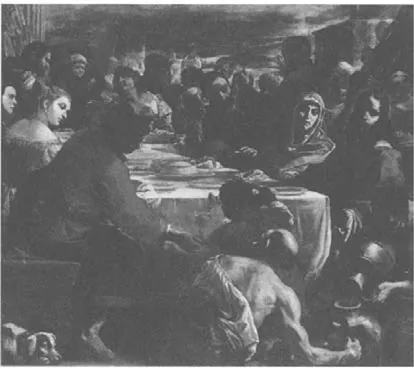

But there are earlier equivalents in painting of Borromini’s sideways composition in a narrow street – radically diagonal presentation of the picture space, as in Mattia Preti’s Wedding at Cana (illus. 2) in the National Gallery. Here the image feels incomplete, as if there is a missing foreground over the edge of the frame, and so the movement into the picture becomes so powerful that it devalues features met along the way. Though most of the actors are seated, the strong diagonal thrust makes the situation feel precarious and temporary. And the weather does not inspire confidence. It is not night-time but extremely dark, suggesting storm. Details are hard to pick out and getting harder; faces are buried or veiled in shadow, and the Biblical story deceives us with its reassuring outcome, for this is a picture about losing one’s individuality in a spatial matrix too powerful to resist.

The kinship between various arts in the Baroque, though extremely marked, can be hard to pin down. It is often argued that Baroque architecture becomes painterly, seeking fluidity and indistinctness much more feasible in flickering brushwork than solid stone. Painters like Preti conceive spatial ambitions which would be more at home in architecture, and one finds poets treating language as a plastic medium, which makes its appeal as a shifting physical mass as well as, or even instead of, an intelligible verbal construct.

2 Mattia Preri, The Wedding at Cana, c. 1665.

It will seem odd to press the blind poet Milton into this role, for in the most obvious sense of the word he is an un-visual writer. Paradise Lost was written from within darkness in some sense: Milton went blind ten years before he began it. The earliest scenes in the poem occur on a darkened stage where the characters flounder locating themselves in an unfamiliar place. But this groping in the dark is also a powerful immersion. If not visual, Paradise Lost is a very plastic work, in which language has a physical presence like a sculptor’s material or like the coloured marble and gold of a Baroque church.

It was a strange, Baroque decision to begin the poem in Hell, a literary equivalent of Preti’s diagonal entry into the picture space. Space in Milton’s poem is not compact and orderly like Dante’s in the Divine Comedy. Not that Dante’s journey through his hierarchical world is at all straightforward – you must go down in order to ascend – but Milton’s poem jumps about, using tricks of perspective to suggest the vastness of his scene. This vastness is presented from the start as relative and historical, indicated partly by our mental distance from the states the poem describes.

If the hunch is correct that Milton the lover of Italy meant St Peter’s as the model for the devils’ hall in Pandemonium, there is a powerful irony in the comparison. However corrupt, any human construction must be inadequate to the task and simply indicate that our perceptions are only approximations at best. In the poem these disparities cause less gloom than this may suggest, and work like a continual play of wit.

Darkness and dynamic movement are exhibited at an intimate level by Milton’s impressionistic grammar, so fertile in spreading confusion or at least uncertainty about whether the word at the end of the line is a noun or a verb, about when the suspended or hovering sense will be allowed to find temporary rest or final closure. So it is a fabric in molten if not fluid state whose proportions and massing undergo change as we move through it.

The involving, even entangling movement of Paradise Lost reshapes the reader’s perceptions in an almost kinetic way. Milton, it is often said, writes English as if it were another language, as if it had inflected endings or unheard-of connectives which could be willed into being in their absence.

A famous nineteenth-century physicist credited Milton’s involuted language with inspiring in him a fascination with physical space. This is to read the poem as Baroque architecture, placing its elements vividly in space, or introducing them in sequences like optical illusions, which a few lines further on show you how to reorder near and far more appropriately. He is the most perspectival of writers, like Borromini a magician of scale. His choice of subject has guaranteed that from the beginning no single vantage point will answer to all its ranges. Even his invocation of the Muse shifts restlessly from place to place and finally to no place, the Holy Ghost brooding over the waters, covering them with wings of enormous extent, but suggesting the most confined figure as well, a prosaic bird, emphatically a creature of limited dimension.

When Satan’s position in the universe is being defined we come up against abrupt lurches of size and profundity, mechanisms which work like jokes or displacements. Satan’s shield is cast behind him like a shadow or like the moon, the moon that an astronomer at evening on a Tuscan hill views through his telescope. So something large, seen from a certain point, is small and surrounded by vast empty distances, and Satan swims into focus and out again.

Then his spear is introduced, bigger than a pine on a mountain, like the mountains the astronomer on his hill finds on the moon. So the spear is irrationally relocated to the mountain within the moon, the moon which is the shield. All the while we are told how big this spear is, but feel that it is nowhere near the right order of magnitude to match its mate, by which it has just been swallowed. In dissolving frames the moon is replaced by the observer on his mount, on which a pine is growing, which becomes a wand waking the locusts which are Satan’s army, which a minute ago were leaves shed by trees in Vallombrosa, a valley no longer shady when they have fallen, or the broken remnants of Pharaoh’s chariots floating on the Red Sea, a later phase in the story than the locusts who formerly threatened the same Egyptian enemy.

Such rich confusions seem to breed faster in Hell. Temporal and spatial contradictions are among Milton’s means of describing evil. But they are also built into our perception of God and our relation to Adam. The poet has chosen an impossible subject in the sense that all the narrative expedients he invents for rendering the unearthly and invisible are misleading in one way or another and need to be dispelled before they get too deeply lodged in consciousness.

Ingeniously, Milton identifies the fallen angels with specific historical figures, the pagan gods of whom we have distant but circumstantial accounts, like anthropologists’ records of tribal practices which shade into legend which is a kind of poetry, and therefore dangerous for Milton. Can one love the names of Astoreth, Thammuz and Rimmon, as Milton clearly does, while hating what they stand for? Can the pagan gods be safely contained by locating them in Hell? Will all this learning lie down meekly and let itself be negated? It is a question met before in the Hymn on the Morning of Christ’s Nativity and answered paradoxically by allowing paganism a long farewell appearance.

Other Baroque works have their own versions of paganism, the Other or Contrary which the ruling doctrine professes not to admit, whose presence is nonetheless strongly felt, creating an unacknowledged tension which powers the work – a tension which subsists for example in Hawksmoor’s conflation of the temple and the church. Cultural ambivalence runs deep in his work and his interest in centrally planned buildings feels more intransigent than Wren’s, even though more veiled. Fervently Catholic designers also exploit such contradiction, using worldly interests to describe spirituality, or sexual passion as a model for ecstatic union with God, as in Bernini’s St Teresa pierced by the angel’s fiery dart executed in chaste white marble.

This was not an aberration of seventeenth-century piety – a similar ambiguity is observable in the spiritual techniques devised by St Ignatius, not himself a Baroque figure but founder of a movement which took off in that period, and the inventor of some of the seventeenth century’s most telling psychic economies. One of the most powerful is ‘composition of place’, whereby the devotee sees in imagination the physical setting of the spiritual event: the road Christ travelled on, the room He ate in, or in the most famous meditation of all, Hell with all its horrors. This vivid imagining is only the beginning. One goes back over it in further sessions, concentrating on the consolations, desolations and moments of spiritual relish it offered on the previous occasion. Sensuous detail is not the final goal, and Loyola’s systematizing of the act of contemplation leads in the end to its contrary: an inflamed love of God. The programme of the Spiritual Exercises: four ‘Weeks’, each with its overarching subject, each of whose days is broken into five exercises or contemplations, each lasting an hour, beginning at midnight and continuing on first waking, sounds rigid but is in fact hypnotic.

The Exercises are an imp...