![]()

1 Whose Funeral?

I begin in the nineteenth century both because it was in this period, more than ever before, that men wore black; and also because it was in this period that the blackness of men’s dress was perceived as problematic – something that men puzzled at, even as they dressed in black. Clearly black served for gender-coding: what disturbed commentators of the time was not this, but rather the way in which, more and more, it appeared men were opting for the dress of death. Alfred de Musset found ‘le deuil’ (the mourning) men wore ‘un symbole terrible’.1 So did other commentators, recording the new fashion with troubled wonder, as if a sombre mystery were unfolding steadily in everyday dress.

Previously men, like women, had dressed in many colours. In the Middle Ages men dressed splendidly if they could afford it. Even the poor wore varied colours – brown and green, a red or blue hat – as medieval illuminations show. In the Renaissance there was a fashion for black, but still black was far from being worn by everyone. And men wore colours in the eighteenth century, and into the first two decades of the nineteenth. But from this point on men’s dress becomes steadily more austere and more dark, and if one consults the fashion journals one can see colour die, garment by garment, in a very few years. By the early 1830s the evening dress-coat and the full dress coat were normally black (though they might, for instance, be dark blue). In the early 1830s trousers might, in the summer, be white (they had ceased to be coloured), but by the later 1830s ‘black trousers or pantaloons were the rule’. Even the cravat did not hold out for long: in 1838 The Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion recorded that the white cravat ‘was driven from all decent society by George IV. He discarded the white cravat and the black became the universal wear.’ For some years the waistcoat was a last redoubt of colour, but in May 1848 The Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion observed ‘the materials for dress waistcoats are black or white watered silk or poplin’. The same changes occurred simultaneously in France, where, in 1850, the Journal des tailleurs noted that formal menswear now consisted solely of ‘un habit noir, un pantalon noir, un gilet blanc et un autre noir; une cravate noire et une autre blanche’: Théophile Gautier regretted in his essay ‘De la Mode’ that men’s dress had become now ‘si triste, si éteinte, si monotone’.2

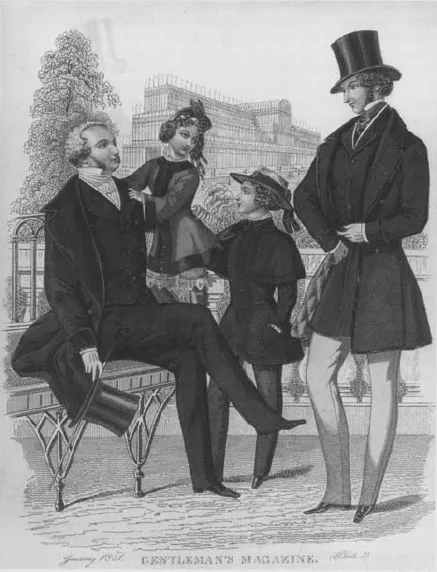

Not everything was black. Trousers and waistcoats might still be white or off-white, and in the frock-coat dark green, dark blue and dark brown fought back in some years and retreated in others. But all the bright colours were gone beyond recall, the tone was dark, the dominant colour was black. The ‘Tailors Monthly Pattern Card of Gentlemen’s Fashions for January 1842’ (illus. 2) contains some dark blues and browns, but most of the garments are black, each of the Gentlemen is wearing some black items, and the Gentlemen in the centre wears a black hat, a black frock-coat, black trousers and black shoes. The opera-goer to his left wears an elaborately brocaded opera-coat, which again however is wholly black, accompanying his hat, trousers and shoes. One can demonstrate the chromatic narrowing that has occurred by comparing the smart clothes people wore in those years with the ‘fancy-dress’ they might wear to balls. For fancy-dress consisted of the clothes worn in other countries, and worn at other times; and as illustrations of the period show, such clothes are full of colour, that is what makes them ‘fancy dress’. Otherwise colour, in any strong sense, was restricted to the military, especially to ‘dress’ uniform, which thus became the serious mode of fancy-dress.

The young gentlemen of 1842 are technically Victorians (Victoria came to the throne in 1837), but they are not yet grave Victorians: they are young, doll-faced, men about town. And since fashion-plates glamourize in a youthful direction, it took fashion-art a little while to register the new mood of gravity and moral uprightness, which later came to be synonymous with ‘Victorian’. Such a figure may, however, be seen in a fashion-plate of 1851 (illus. 3), where the seated man, though young-faced and cherry-lipped, as the genre required, still visibly has jowls, grizzled whiskers and a fair measure of white hair. It is not clear whether he is to be construed as the father or grandfather of the girl and boy: fathers could in any case be grandfatherly. But he sits with the stiffness, the buttoned-up-ness, the rigid verticality that Dickens attributes to many of his characters – features that the artist has attempted to render dashing. The young gentleman also wears black, as he will for much of his life. In the background, the year being 1851, stands the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park.

It was a great change. Men wanted to dress in a smart kind of mourning, and as a result the nineteenth century looked like a funeral. It was seen as a funeral by writers of the time. Baudelaire said of the frock-coat: ‘Is it not the inevitable uniform of our suffering age, carrying on its very shoulders, black and narrow, the mark of perpetual mourning? All of us are attending some funeral or other.’ Balzac observed that ‘we are all dressed in black like so many people in mourning’. The same thought was independently expressed in England by Dickens, who then extended the conceit from the clothes people wear to buildings, even cities. In Great Expectations, when Pip arrives in London, he finds Barnard’s Inn wearing ‘a frowsy mourning of soot and smoke’, and as to the black-clothed, black-jowled Mr Jaggers, his own ‘high-backed chair was of deadly black horsehair, with rows of brass nails round it, like a coffin’. A powerful macabre imagery runs through Dickens, and especially through his late novels, which sees life in England, and life in London, as being one ghastly funeral, a funeral that is nightmarish because it never comes to an end. In Dombey and Son, the light that enters Dombey’s office leaves ‘a black sediment upon the panes’.3

3 Fashion-plate, hand-coloured engraving, from The Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion, January 1851.

It is perhaps because they are the centre of a funereal world that real funerals, actual interments, take such a strong hold on Dickens’s imagination. They are terrible in the labour they make of their mournfulness, no good way of meeting death. In the description of the funeral of Pip’s sister in Great Expectations we see what is alive in Dickens protesting, in the high-spirited play of fancy with which he both evokes and evades the dismalness. There is a hard-bitten, an exasperated, catch in his voice:

The remains of my poor sister had been brought round by the kitchen door, and, it being a point of Undertaking ceremony that the six bearers must be stifled and blinded under a horrible black velvet housing with a white border, the whole looked like a blind monster with twelve human legs, shuffling and blundering along under the guidance of two keepers.

Both the humour and the pall are over everything, even over the new, rapid, noisy railway system, which, for all its coal-dust, smoke and soot, might be thought one of the less sepulchral features of Victorian England. But in ‘Mugby Junction’ there are ‘mysterious goods trains, covered with palls and gliding on like vast weird funerals, conveying themselves guiltily away from the presence of the few lighted lamps, as if their freight had come to a secret and unlawful end’.4

Baudelaire and Dickens have the same vision of their suffering age. In the light of this concurrence one may ask, what had the nineteenth century suffered? What was being mourned?

Baudelaire gave a political explanation: ‘And observe that the black frock-coat and the tail-coat may boast not only their political beauty, which is the expression of universal equality, but also their poetic beauty, which is the expression of the public soul.’ For him the black frock-coat was the uniform of the democratic spirit, of all the democratic bourgeois. He said ‘a uniform livery of grief is a proof of equality’. Democracy had killed a precious individuality, and following that death democratic life could only be ‘an immense procession of undertakers’ mutes, political mutes, mutes in love, bourgeois mutes’.5

For Baudelaire, black, like death itself, was a leveller. And the association of black dress with democracy is persuasive, if one thinks not only of France, but of nineteenth-century America, where black was very widely worn. Black was so dominant in the United States that Dickens, for example, was thought garish on the strength of light trousers, a coloured waistcoat, and blackly glittering boots. The St Louis People’s Organ complained in 1842: ‘He wore a black dress coat ... a satin vest with very gay and variegated colours, light coloured pantaloons, and boots polished to a fault. . . . His whole appearance is foppish, and partakes of the flash order. To our American taste it was decidedly so; especially as most gentlemen in the room were dressed chiefly in black.’6 Black was fashionable in England too, however, where the democratic commitment was less strong, to say the least. The politics of the move to black are complex.

In what way was the change political? J. C. Flügel, in The Psychology of Clothes, asks what were the causes of ‘the Great Masculine Renunciation’, and finds them in ‘the great social upheavals of the French Revolution’:

It is not surprising. . . that the magnificence and elaboration of costume which so well expressed the ideals of the ancien régime should have been distasteful to the new social tendencies and aspirations that found expression in the Revolution.7

He argues that these tendencies and aspirations promoted simplification and uniformity of dress. There must be a measure of truth in this. What Flügel does not explain is why these tendencies and aspirations led to darkness and to blackness – hardly a natural corollary, even if one allows that the forces that will turn a society upside down are likely to be severe. Nor, in fact, was the process of change a simple matter of the vanishing of finery as the guillotine fell. Both the plain fashion, and then the dark and black fashion, were not actually set in revolutionary France. They were set in England, and only later taken up elsewhere. The plain style had its origins not so much in social levelling as in the practical requirements of the English gentry, travelling not in carriages but on horseback. And as to blackness, the first item of menswear to go black was not the daytime frock-coat of the democratic bourgeois, it was evening dress, the ‘dinner-jacket’ of high society.

The dinner-jacket epitomizes the change that occurred, for up to a certain date in the early nineteenth century, men’s evening wear changed freely and could be in many colours. Then, in the later 1810s, the smart began to wear black in the evenings, and evening wear has stayed black ever since. The present century, it is true, has seen the occasional white coat at dinner: but black has remained dominant, and indeed the dinner-jacket or tuxedo that is worn today is not a great deal different from what would have been worn 170 years ago. It was, especially, a fashion for gentlemen, propagated for instance by the novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Baron Lytton, author of Pelham, or the Adventures of a Gentleman. For Pelham, only one colour will do. ‘I do not like that blue coat’, his mother tells him, ‘You look best in black – which is a great compliment, for people must be very distinguished in appearance in order to do so’. And when Pelham prepares to go out for the evening at Cheltenham, he commands his man:

‘Don’t put out that chain, Bedos – I wear – the black coat, waistcoat, and trousers. Brush my hair as much out of curl as you can, and give an air of graceful negligence to my tout ensemble.’

If ‘negligence’ should seem a surprising component of evening-dress smartness, we may turn up Maxim vu in the set of 22 maxims on dress given in chapter 44 of Pelham:

To win the affection of your mistress, appear negligent in your costume – to preserve it, assiduous: the first is a sign of the passion of love; the second, of its respect.

Black for Pelham, then, is romantic, or Romantic, as well as distinguished. He will be a man in black, or a man in dark coloured clothes, at all times of day. So he notes, as he attaches his jewellery in the morning, ‘I set the chain and ring in full display, rendered still more conspicuous by the dark-coloured dress which I always wore’. Circulating in black, as did his author also, Pelham is elegantly, yet dashingly, gloomy: the novel was an international bestseller, and helped broadcast the fashion. There is scant sign of democracy about Pelham’s black, it is much more distinguished, distingué, though associated also with the leisured melancholy of the Romantic hero: the graveyard pose, the mysterious past, the blighted heart, the blazon of death, with all the genteel Hamletizing that was in those years à-la-mode.8

The fashion for Romantic melancholy passed away, but evening dress stayed the same and stayed black, and to explain how the fashion originated is not to explain how it was fixed. And it is the fixing of black that is in question, for black fashions may come and go, but in 1820 or so black came and did not go. As to Bulwer-Lytton and the black dinner-jacket, the consideration to turn to, as shedding relevant darkness, is that Bulwer-Lytton was a dandy: for it was not directly in a trundling of tumbrils, but rather in a stalking saunter of dandies that the plain and then dark styles were launched as fashion.

Bulwer-Lytton, or rather his creation, Pelham, was picked out by Carlyle in Sartor Resartus as the ‘Mystagogue, and leading Teacher and Preacher’ of ‘the Dandiacal Sect’. Nowadays the word dandy might conjure the image of a colourful fop, but that is the wrong image. In the eighteenth century, the beaux and later the macaronis may have been elaborate and polychromatic: what the dandies introduced was a restrained and sober smartness. The first dandy was Beau Brummell (though the word ‘dandy’ was applied to him after his apogee). He lived for elegance, going for his coat to one tailor, for his waistcoat to another, for his trousers to a third. The detail most often re-recorded is that he gave a good part of the morning to tying his cravat right: when one visited, there would be a pile of cravats slightly crumpled on the floor, while the valet explained ‘These, sir, are our failures’. But his clothes were simple: just trousers, waistcoat and coat, in the sparest style but of the best material and of perfect cut. ‘Cut’ itself, close, sharp and smart, acquires, with the dandy, a pre-eminent importance, hence Pelham’s Maxim XIV, ‘The most graceful principle of dress is neatness’.9

In the evenings Brummell would appear in a black waistcoat and tight-fitting black pantaloons: in contemporary prints he cuts so sharp a dash, he can even seem a trace satanic (illus. 4).10 On his advice, his friend the Prince Regent wore black in the evening: and it is with the fashion-setting friendship of Brummell and ‘Prinn...