![]()

09. 1981

Rosetta Brooks: There seems to be a quite definite change in artists’ use of photography in the 1970s. From the almost documentary use of conceptual artists, it seemed to evolve into a reflection of the medium itself. How do you relate this change in your work?

I think there are two main attitudes. You can think about the medium in almost purely technological terms: to take a ‘photograph’ is to exercise a number of options – plane of focus, shutter-speed, aperture, framing, angle and so on – and the ‘content’ of the work becomes your choice from amongst these options and the way you structure them. This is an attitude which comes very directly out of Greenbergian modernism. Or you can start from the fact that photography was invented to give an illusionistic rendering of some aspect of the world in front of the camera – which leads into considerations of representation and narrative – which is what I’m interested in.

You’ve been very critical of modernism in fact.

I’ve been critical of the political conservatism of modernism, of its complicity in the Cold War cultural politics of the 1950s for example, but we should remember that the humanist documentary realism of Steichen’s ‘Family of Man’ photography show served the same ideological ends as painterly abstraction in that same period. When I said that the first sort of attitude comes out of Greenberg, I should have said it comes out what Greenberg says about painting. Basically, modernism says you should ground your practice in its specificity – that which it has to offer that is different from the other media around it. Obviously, how you define that specificity is crucial. The technology of the medium is just part of this specificity – no need to make a fetish of it.

On one level your work might be seen as Adorno’s nightmare – advertising for its own sake. How do you respond to this sort of criticism – dismissing the works as radical advertisements? Do you feel you inherit the limitations of the advertising image – the singular, unambiguous reading, consumed in a moment?

Both advertisers and critics of advertising like to believe in that Thurberesque beast, the ‘unambiguous reading’ – I don’t believe it ever existed; it’s certainly extinct now. The form of the text, the context in which it’s produced, the mind of the reader, all can reverse the communicative intention. Take that ad in the London Underground which shows a woman opening her garage door to reveal a tube-train – I saw one poster where someone had added in pencil ‘so that’s where they’ve all got to’. That familiar sort of semiotic subversion wouldn’t be possible if readings could be made unambiguous. As for the speed of consumption … from what I’ve just said, obviously I don’t accept the idea of ‘consumption’ – there’s always some investment of meaning made by the reader. Now certainly you can design the text to encourage a reading which is closer to the ‘consumption’ end of the scale than the ‘investment’ end, one which is read more easily and therefore faster – which is what I did when I made posters for the street. Other texts I deliberately construct to slow down the reading, to make it more difficult.

Your pictures and your texts often seem like quotations. One gets no sense of a single voice from the words. The texts range from the documentary to the almost poetic; but I find there is more of a trace of style in the photographs. They all at least remain within the documentary genre.

What I’ve always aimed for in the texts is a ‘lapidary’ style – the idea originates in classical antiquity, it’s a style suitable to inscriptions carved in stone: terse, economical. The work called us77 has three distinct voices: didactic, narrative and paradoxical. As far as the images are concerned, I used a documentary style because of three things: first, I believed that was what photography did best; second, I tend to have a cut and dried approach to things, so I wanted to put myself in a situation – the street – where it was impossible to be fully in control; third, who knows what appearances of our period are going to be interesting to people in 100 years time or more? Maybe it’s something in the street we don’t even think about now.

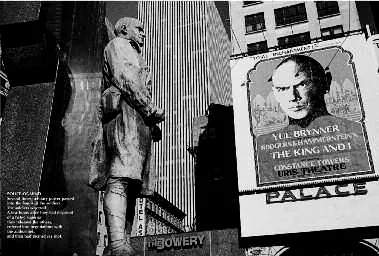

The monumental transient image of the advertisement was obviously something you were thinking about in the ‘US’series. The pieces themselves were all big, giving the impression of interior billboards. ‘Police of Mind’ (illus. 4), for example, is a strong, spatial experience at that scale. Yul Brynner’s head almost seems to come out at you from the space of the cityscape. It seems to reproduce that giddiness in looking up in New York, of being forced to look higher and higher and confronting representations which are proportionally bigger and bigger. The piece seems to be about this historical dominion of space … the way that the monumental hero of an earlier epoch is dwarfed by the cinematic hero.

4 ‘Police of Mind’, from US77 (1977), one of twelve parts, 100 × 150 cm.

It’s interesting to me that you should say that, because although I was thinking about power relations in that panel, in the whole piece in fact, I never consciously gave the image that particular reading – a reading in terms of the power of the ‘cinematic imago’.

Well, Yul Brynner’s head is a part of the walls which have boxed in the horizons which the stare of the soldier was intended to suggest. The soldier is dwarfed by becoming the object of the intimate stare of the cinema.

When I did that piece, I was aware of something in that image which I felt was there for me – as a coherent meaning, but which escaped me. It’s interesting for me personally because I feel you’ve just supplied the repressed meaning; repressed perhaps, because as a worker in a largely marginal art institution, I feel castrated when confronted with the cultural power of the movie industry.

Like the old soldier?… But you are not merely powerless. The photograph exerts a power. It makes us see what we might otherwise overlook. It gives us a privileged perception of the coincidence of these different representations in space. There’s a third vantage point – yours. The most powerful is the invisible one – the artist’s or photographer’s.

Certainly the act of photography is an act of appropriation: it’s also a way in which we can return the looks directed at us from advertising, and it can be an aggressive act, an act of revenge.

It is interesting that as your work has become more involved with sexuality and with sexual stereotypes that the works have become more associative.

It isn’t just in respect of sexuality that the texts have become more associative – it becomes a necessary condition of the way I work. The text superimposed on the image had to be comparatively small in area, otherwise it would take on too much independence – which meant it had to be short otherwise the typeface would be too small to read. As there was a lot I wanted to put into that small text, it meant a work of condensation, of compression into a small space. Compressing a text like that meant breaking, short-circuiting, the usual sorts of linear connections we expect to be offered. It means shortening the horizontal lines which are actually present, set in type, and relying on the vertical chains of associations which are always potentially there in your mind.

What do you think about the tendency in advertising to separate the word and image? I’m thinking about the much-discussed Benson and Hedges campaign, and in recent Guinness advertising, where the text is absent altogether, or in 1970s fashion photography, the tendency to give the image greater and greater autonomy from the product.

All texts depend on, are associated with and are invaded by, other texts. Advertising has known this for a long time. If, for example, you use the caption ‘Play it again, Sam’, then you instantly engage with a whole narrative, a morality, a cult and so on – all of which is activated by those four words. What is being recognized now is that you don’t actually need to put words on the image because the words are already in the mind of the viewer – again, this is hardly new knowledge; painting in the Renaissance was based entirely on this. In more recent history we got the silly dogma of the ‘purely visual’ that the more academic of our art schools still teach. Certainly, light striking the retina is something ‘purely visual’ – but that retina is connected to the brain, and that brain doesn’t see the retinal image. What the brain ‘sees’ is mediated by prior experience and knowledge which is both visually and verbally encoded. Dreams are examples of mental activity that turns words into images, and vice versa. Dreams also show us how profligate this mental activity can be; and to control this you need some words. Those ads which, of late, have seemed so empty of language, all contain words, but words now keep a low profile.

Where does the idea of an image/text fusion come from? I think of the artist as film director – wholly in charge of the scenario. Cinema, I suppose, is the ultimate fusion of the word and the image. Working in series imposes an equivalent linear ordering of encounter with the image. Do you wish you were a film director?

I do from time to time wish I was making films, but not because I’m unhappy with my own form of practice – it’s rather that I’m unhappy with the conditions of distribution and consump – tion of that practice. It’s like this – one works for an imaginary audience; now for someone with my sort of theoretical and political concerns who makes films there is a real audience to correspond to that imaginary audience, and there are modes of distribution for reaching that audience. More or less the same audience is potentially there for the type of work I produce – for example, I know there were a lot of people who went to the recent shows of feminist work at the ICA, and who went to the ‘Three Perspectives’ photography show at the Hayward in 1979, who never normally set foot in a gallery – but there’s no corresponding distribution network. I made a large work in Berlin – Zoo. It’s been shown once in England – at the Hayward in 1979 as part of the ‘Annual’ – and it’s unlikely that it will be shown again anywhere in this country. If I had made a film in Berlin, then that film could have gone several times round one or other of the universities, and other networks by now. Also, with film, there’s always the possibility of moving into a more general audience arena: with art, if it’s been hung in the Hayward, that’s it – finished. As an avant-garde filmmaker friend said to me: ‘You’re at the centre of a periphery – I’m at the periphery of a centre.’ I spoke about this to another filmmaker, and she told me that I overestimated the conditions for theoretical/political filmmaking – she said that you should consider the work as being not one of ‘reaching’ an audience but one of creating an audi-ence – but how is that possible without minimal access to the means of distribution?

But isn’t art inevitably peripheral? Most artists could feel that margin-ality is the price of independence.

There’s a position on the ‘left’ in which ‘art’, indeed any form of cultural activity, is seen as ‘peripheral’ to the ‘real world’ of party politics and economic class struggle. There’s a position on the ‘right’ which agrees with this and welcomes it as a ‘guaranteeing the independence’ of artistic creativity. You’re then offered a choice as to which square to occupy on a checkerboard of positions – any position as long as it’s black or white. I think it’s important not to accept any games played on this board. Cultural production, to which ‘art’ contributes, involves social relations and apparatuses, and has definite societal effects. Artists are not independent – socially, economically, ideologically, politically – for all it suits some of them to pretend that they are. But neither are they ‘a cog and a screw’ in the party machine.

Your work uses a format which relates to a cultural mainstream of image use. Marginality seems to be an essential part of the strategy.

I think what’s at issue here is a metaphor. You use the word ‘margin’. A margin is a space running along the edge of something to which it doesn’t belong. I’ve used this term myself – ‘society marginalizes its artists and intellectuals’ – that sort of idea. It’s a metaphor which slips out easily, but I wonder if it’s the most appropriate one. Maybe ‘fringe’ would be better. If I’ve got it right, ‘fringe interference’ is what takes place where different ‘wave forms’ encounter each other. If you throw three stones into a pond and watch the ripples, then there are places where those waves are encountering each other and producing something new. So ‘fringe’ allows for a more dynamic and de-centred picture than ‘margin’. I feel I’m working across the fringe areas – for example, as I’ve said already, where ‘art’, ‘advertising’, ‘documentary’, ‘theory’, etc. overlap, but the very fact of cultural production then taking place in those areas of overlap means that ‘ripples’ then emanate from those points. Definitions of art change as a result – for example, the idea of what it’s possible for an art exhibition to be about. The changes are resisted, but then the resistance becomes the very sign of change. Even exclusion, that silent form of resistance, marks a space which is destined to be occupied.

![]()

10. 1986

The intermediary of money guarantees the abolition of difference and the creation of equivalence – much as, in horror films, Dracula’s kiss converts the contradictory social heterogeneity of the living into the single-minded unity of the undead. Dracula’s victims lose their identity, along with their blood, in exchange for parity with their victimizer, an analogous transfusion of contents and status is performed at the art auction: the painting is drained of its symbolic value, which passes to its purchaser in the form of prestige, in exchange for investment value. Part of the symbolic value of the painting, of course, inheres in the (magical) belief that its essential substance is congealed ‘creativity’ – this too (by the same magic of communion) becomes the property of the purchaser. Hence the catalogue to an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1983: The First Show: Painting and Sculpture from Eight Collections 1940–1980. In place of the customary names of artists, the cover carries only the names of the collectors; the greater part of the catalogue is devoted to interviews with them; the essays in the catalogue are about the collectors and their place in the history of the art of collecting. In short, the discursive forms of dominant, ‘common sense’, art criticism are transferred, unmodified, from ‘art and artists’ to ‘collections and collectors’. For example: ‘Rowan’s is a cultivated, sensuous taste that first found expression in his renowned collection of colour-field paintings’; or, again, ‘The collection of Count and Countess Giuseppe Panza di Biumo is a brilliant creative endeavour unlike any we have seen in this century. Guided by his own innate and dramatic grasp of the beauties of architectural space …’ and so on. I read all this in Los Angeles, but am now writing in London and am aware of an opinion here which would attach no more significance to this show than that of a mere quirk of the Californian ‘grotesque’, the product of a singularly unmixed economy which dictates that museum and university must flatter private wealth or perish; in Europe, the state cocoons those it charges with the preservation of eternal verities and values from such undignified soliciting. This, of course, is untrue – here in Thatcher’s Britain it becomes patently less true by the minute.

…

It is thus that art history, criticism, the market and the museum, mutually circulate their meanings: a fashionably nostalgic de Chirico revival amongst young painters in Italy, selected for capitalization and promotion by art dealers, results in the upward valuation of works by de Chirico, a major exhibition of his work, and the millionpound price tag [on a de Chirico painting], which in turn underwrites the spiralling prices of his young ‘followers’. All meanings here contribute to, and are swallowed up in, the roar of fashion; the heady alternation/alteration which converts ‘different’ into ‘same’; a dizzy whirl whose very velocity, like a gyrating toy, guarantees its stability; a vortex of effects which sucks a vacuum into its own core, such that it no longer makes sense to posit the market – the economy – as ‘origin’. The ‘centre’, prime cause (like power itself, in Foucault’s description), is now everywhere and nowhere. In contemporary capitalism […] the market is ‘behind’ nothing, it is in everything. It is thus that, in a society where the commodification of art has progressed apace with the aestheticization of the commodity, there has evolved a universal rhetoric of the aesthetic in which commerce and inspiration, profit and poetry, may rapturously entwine. Compare, for instance, the following two passages (they are by no means exceptional, they are typical), the first is from Vogue magazine:

As the sun descends the butterfly-bright colours that flourish at high noon give way to the moth shades. The tones are pale, delicate. These are the classic Mayfair colours, White, naturally, takes pride of place, but evening white lightly touched with silver or sometimes gold. Mayfair colours are almond, pink and green, dove greys and blue with the occasional appearance of what can only be described as peach. Jewellery is kept to a...