- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

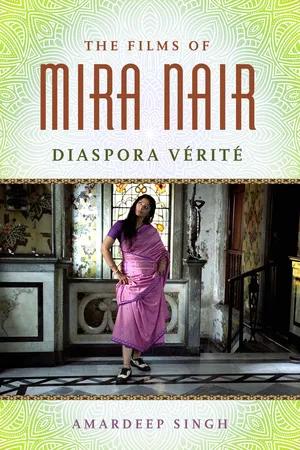

The Films of Mira Nair: Diaspora Vérité presents the first, full-length scholarly study of her cinema. Mira Nair has broken new ground as both a feminist filmmaker and an Indian filmmaker. Several of her works, especially those related to the South Asian diaspora, have been influential around the globe.

Amardeep Singh delves into the complexities of Nair's films from 1981 to 2016, offering critical commentary on all of Nair's major works, including her early documentary projects as well as shorts. The subtitle, "diaspora vérité," alludes to Singh's primary theme: Nair's filmmaking project is driven aesthetically by her background in the documentary realist tradition (cinéma vérité) and thematically by her interest in the lives of migrants and diasporic populations. Mainly, Nair's filmmaking intends to document imaginatively the experiences of diasporic communities.

Nair's focus on the diasporic appears in the long list of her films that have explored the subject, such as Mississippi Masala, So Far from India, Monsoon Wedding, The Perez Family, My Own Country, The Namesake, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist. However, a version of the diasporic sensibility also emerges even in films with an apparently different scope, such as Nair's adaptation of Thackeray's Vanity Fair.

Nair began her career as a documentary filmmaker in the early 1980s. While Nair now has largely moved away from the documentary format in favor of making fictional feature films, Singh shows that a documentary realist style remains active in her subsequent fictional cinema.

Amardeep Singh delves into the complexities of Nair's films from 1981 to 2016, offering critical commentary on all of Nair's major works, including her early documentary projects as well as shorts. The subtitle, "diaspora vérité," alludes to Singh's primary theme: Nair's filmmaking project is driven aesthetically by her background in the documentary realist tradition (cinéma vérité) and thematically by her interest in the lives of migrants and diasporic populations. Mainly, Nair's filmmaking intends to document imaginatively the experiences of diasporic communities.

Nair's focus on the diasporic appears in the long list of her films that have explored the subject, such as Mississippi Masala, So Far from India, Monsoon Wedding, The Perez Family, My Own Country, The Namesake, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist. However, a version of the diasporic sensibility also emerges even in films with an apparently different scope, such as Nair's adaptation of Thackeray's Vanity Fair.

Nair began her career as a documentary filmmaker in the early 1980s. While Nair now has largely moved away from the documentary format in favor of making fictional feature films, Singh shows that a documentary realist style remains active in her subsequent fictional cinema.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

MIRA NAIR’S DIASPORA VÉRITÉ

Mira Nair is a filmmaker who uses a documentary realist sensibility to explore the lives and experiences of diasporic subjects. Nair, who made her first film in 1979, is best known for her crossover hits Salaam Bombay! (1988) and Monsoon Wedding (2001), but all told she has made (as of the present writing) twelve feature-length fiction films, five documentaries, and half a dozen short films. Taken together, her body of work gives her a unique status as an Indian diasporic artist with links to the Anglo-American as well as Indian cinema worlds as well as an ability to bridge the arthouse and the mainstream. While there is currently no shortage of critical engagement with Nair’s most influential films, the disciplines of film studies and postcolonial media studies have perhaps not thus far taken adequate stock of the breadth of Nair’s contribution to the representation of diasporic lives throughout her long career or discovered the essential unity of her filmic oeuvre. This study aims to correct that oversight with a comprehensive look at Nair’s major works.

Both Nair’s earlier and her more recent films are marked by her early exposure, first at Harvard University and then in the New York City film community of the early 1980s, to the cinéma vérité style of documentary realism. While Nair made a format shift from documentary to fiction film beginning in 1987, she has continued to remain invested in a documentary realist aesthetic since then. Nair has cultivated a filmmaking style that emphasizes naturalistic acting over melodrama, that minimizes the evidence of narrative or visual manipulation on screen, and that aims to document the lives of ordinary people from a diverse range of racial and class backgrounds. Nair has also always been invested in filming on location rather than in studio, using mobile, eye-level cameras wherever possible, and synchronous sound rather than overdubbing (even as the latter remains quite common in commercial Hindi cinema). Also, in making Salaam Bombay!, Monsoon Wedding, and, most recently, Queen of Katwe, Nair has used amateur actors filmed in their own everyday settings for added realism. While these techniques are not universal in Nair’s work, I will argue that they do largely define her approach to filmmaking at its best. In The Films of Mira Nair: Diaspora Vérité, I aim to show that the filmmaker uses documentary realism in order to show that the prospect of migration, dislocation, and even exile offers her characters a potential path to freedom from social and cultural repression. The phrase “diaspora vérité” in my title aims to encapsulate the way Nair uses documentary realist techniques to explore diverse experiences of migration and displacement in her films. I intend the phrase to be suggestive rather than technical—“diaspora vérité” alludes to the sources of Nair’s aesthetic sensibility, but it also gestures towards the filmmaker’s commitment to social justice, especially with respect to women and socially and economically marginalized groups.

Nair’s films cannot be said to be wholly defined by any singular national or linguistic tradition in cinema; rather, they reflect a wide range of geographical and cultural contexts. Her polyglot films often stretch conventional limits on spoken language associated with national and language-specific cinemas, and they use transnational casts, crews, and production teams. Nair’s films are also marketed and distributed internationally; while she is not alone in that, she is one of very few working filmmakers to be an established name amongst both South Asian and Euro-American filmgoing publics. Insofar as her work has so consistently focused on themes of migration, travel, and cross-cultural encounter—themes that have come to define the cultural landscape of the current globalization era—Nair might be one of a handful of diasporic film directors whose work has helped transform the scope of contemporary world cinema. Besides immediate Indian diasporic peers such as Gurinder Chadha and Deepa Mehta (whose films will be discussed in greater detail below in comparison to Nair’s own work), other directors that come to mind as peers in Nair’s case are Alejandro Gonzales Iñarritu, Alfonso Cuarón, Jane Campion, and the early Ang Lee. Close analysis of those filmmakers’ quite heterogeneous works falls outside of our present scope, but what one sees in all their work is a deep interest in exploring the cultural and psychological effects of migration and displacement—social phenomena that are at the core of the current globalization era. It is not an accident that this short list of Nair’s directorial peers is also heavy on individuals who have done much of their most influential work in countries other than the ones where they were born.

A central focus on the theme of diaspora is readily evident in several Nair films that are centrally focused on immigrants and refugees in the contemporary world. Some of the relevant titles have already been mentioned; a more inclusive list of Nair films that are self-evidently diasporic would include So Far from India, Mississippi Masala, My Own Country, The Perez Family, Monsoon Wedding, The Namesake, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist. Domestic (intranational) displacement is also centrally figured in India Cabaret, Salaam Bombay!, and Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love. Further, Nair’s two commercial period pieces—her 2004 adaptation of William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, and her 2009 biopic Amelia, about the American aviator Amelia Earhart—also figure displacement in important ways. A quick look at that array of titles also immediately underscores the centrality of women’s stories in Nair’s works: from the above list, which includes several of Nair’s documentaries, all but two of the films named have women as either protagonists or coprotagonists. And a surprising number of those films, from Mississippi Masala to Vanity Fair, feature female protagonists who face constraining familial pressure and social limitations—and use the possibility of departure and migration as a means of escape from traditional social structures.

Before we explore these aspects of Nair’s approach to filmmaking in greater depth, a general introduction to the filmmaker and her works is in order. This will be organized below into a brief biographical sketch, followed by a more in-depth contextualization of Nair as a postcolonial and diasporic Indian artist, as a feminist filmmaker, and as a participant in an international art cinema culture.

Let us begin by briefly rehearsing Nair’s general profile as a filmmaker. Nair is arguably the most accomplished filmmaker in the current generation of diasporic film directors of Indian origin, company that includes the aforementioned Gurinder Chadha and Deepa Mehta, but also Shekhar Kapur, Tarsem Singh, Jagmohan Mundhra, Ismail Merchant, Kiran Rao, Pratibha Parmar, M. Night Shyamalan, Prashant Bhargava, and a number of others. Nair has been nominated for an Academy Award, and she won the Caméra d’Or Prize at the Cannes Film Festival (for Salaam Bombay!) as well as the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival (for Monsoon Wedding); she is only the second woman director to ever win the latter prize. But Nair must also be seen in association with a group of avant-garde feminist filmmakers from an international background whose films began to emerge in the 1980s and ’90s, including Julie Dash, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Jane Campion, Claire Denis, and Lizzie Borden; an earlier generation of feminist film critics included Nair as part of an emerging international women’s art cinema (see Stuart 1994). Just as her awards indicate Nair’s reception within the international community of film critics and scholars, several of Nair’s films have been major commercial successes, challenging the divide between the art house and the mainstream. With her two signature crossover successes, Salaam Bombay! and Monsoon Wedding, Nair broke new ground for Indian art films in the international film market; these films also had a surprisingly large impact on the mass market within India itself, despite the gap between Nair’s visual and narrative styles and the styles prevalent in the various commercial Indian cinemas.

Biographical Sketch of the Filmmaker

Nair’s approach to filmmaking is clearly marked by a set of quite singular personal experiences—a family background that made her emigration from India in the 1970s possible, as well as continuing social and familial connections that have influenced her approach to India after the Indian government’s move towards liberalization radically transformed urban Indian life in the 1990s. Nair was born in 1957 in the state of Orissa, in eastern India. Her ethno-linguistic background is Punjabi, and many of her family members are today among the large cosmopolitan Punjabi community that has established itself after 1947 in New Delhi. Nair herself was raised partly in eastern India, in Orissa, where her father, Amrit Nair, a member of the Indian Administrative Service, was stationed for several years. Nair’s mother, Praveen Nair, is a social worker who worked with Orissa’s Social Welfare Board, the Red Cross, and famine relief efforts before eventually signing on to administer Nair’s own charity organization for street children in Delhi, the Salaam Baalak Trust, for several years (Bharadwaj 2007). Nair has at times described how her relationship with her parents, especially her father, impacted her career choices in the early stages (her father played a key role in enabling her to go abroad to study at Harvard University in 1976). However, in an interview from Cineaste in 2004, Nair also described how Amrit Nair’s connection to the Indian bureaucracy inspired her—negatively—to aim for something different in her own career. As she puts it, “I don’t think I got political awareness from him [Amrit Nair] because I viewed bureaucrats as having to ride the winds of the ministers that were in power …. Political awareness came almost as a result of questioning, rather than admiring, that” (Badt 2004: 12). Nair’s comment here is part of a longer conversation about political awareness, but it is also valuable as part of a biographical account. So much of the trajectory of Nair’s career from that point forward is connected to that early choice to follow a different path—to find a way to defy the prevailing social, political, and even aesthetic norms of middle-class Indian life in the 1970s.

Most of Nair’s primary and secondary education occurred at Tara Hall, an Irish Catholic boarding school in Simla heavily oriented toward British colonial values (it was here that Nair says she first encountered Thackeray’s Vanity Fair). Nair began her postsecondary education at Miranda House at the University of Delhi, where she intended to major in sociology but instead became heavily involved in the theater, acting in English-language plays like Antony and Cleopatra, as well as political and experimental theater associated with Barry John’s Theatre Action Group. Nair played against friends and future collaborators in this period, including Khalid Tyabji (who would later perform under Nair’s direction in Kama Sutra), and Lilette Dubey (one of the stars of Monsoon Wedding and a major figure in the Delhi theater world in her own right). In 1976, Nair transferred to Harvard University on scholarship, where she studied documentary film after finding that Harvard’s theater department was too conservative for her interest (Redding and Brownworth 1997: 165). At Harvard, Nair made many connections that would be important to her future, professionally and personally. Perhaps most importantly, it was at Harvard that Nair met her future repeat collaborator and fellow Indian expatriate, Sooni Taraporevala. Nair also met her first husband and collaborator, the photographer Mitch Epstein, at a Harvard summer school course on photography. Epstein would be an important collaborator on Nair’s early documentaries, including So Far from India, where he is credited as cinematographer; Epstein also did production design for Salaam Bombay! Nair graduated from Harvard in 1979, submitting as her senior thesis her short film Jama Masjid Street Journal, which would be screened at New York’s Film Forum in 1986. Though not widely known today, a videotape version of Nair’s Jama Masjid Street Journal has been preserved and is available at a handful of university libraries as well as through Icarus, an academic film distributor (this early short will be discussed at greater length in chapter 2).

After graduating from Harvard, Nair and Taraporevala both relocated to New York, though they did not immediately begin to work together. For her part, Nair sought out the cinéma vérité documentary filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker, who, as she’s indicated, helped her secure the grant that would enable her to make her first feature-length documentary, So Far from India (see Muir 2006: 29). Nair continued to make documentaries, including Children of a Desired Sex (1987), for Canadian television (Cine-Com, Montreal), and India Cabaret (1985); the latter film won several awards including Best Documentary at the Global Village Film Festival in New York (Foster 1995: 277). But the path of Nair’s career changed dramatically when the success of Salaam Bombay! in 1988 opened up Hollywood studio financing for her next feature films, Mississippi Masala and The Perez Family. Nair also used her personal proceeds from Salaam Bombay! to create a charity for slum children in Delhi, the Salaam Baalak Trust; that organization is still active.

Around 1989, Nair met the writer and historian Mahmood Mamdani while on a research trip to east Africa related to the project that would become Mississippi Masala. Mamdani, a member of the Indo-African community in Uganda exiled from the country by Idi Amin in the early 1970s, had, by 1989, returned from England and resumed teaching at Makerere University in Uganda. In an interview, Nair described the beginning of the relationship as follows: “I had heard of him [Mamdani]; he was a political writer and academic who had written a very moving piece on the Asian expulsion from the country…. I fell in love with the country and with him” (Stuart 1994: 215). Nair and Mamdani lived in South Africa for a time in the mid-1990s, while Mamdani was teaching at the University of Cape Town. Nair and Mamdani’s son, Zohran, was born during this period of transition for the couple, in 1991. While in South Africa, Nair directed a short fiction film dealing with the end of the Apartheid era, The Day the Mercedes Became a Hat (1993); she also began working on the script that would become Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love. Since 1999, Nair and Mamdani have been largely based in New York (they also own a house in Kampala, Uganda), where Mamdani teaches history at Columbia University; Nair also occasionally teaches courses on filmmaking at Columbia. In 2000, Nair founded a filmmaking school for girls in East Africa called Maisha Film Lab, which she continues to work with during regular visits to Uganda. One of Maisha’s most prominent alumni is Lupita Nyong’o, who won an Academy Award for her role in 12 Years a Slave (2014), and who also starred in Nair’s recent film Queen of Katwe (2016). Since the early 2000s, during the fall, winter, and spring seasons, Nair often appears as a speaker and honoree at cultural events in New York City, as well as at universities and film festivals across the United States. Nair has recently released two new major film adaptations, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, starring Riz Ahmed and Kate Hudson, and Queen of Katwe, starring Lupita Nyong’o and and David Oyelowo. While not without its flaws (see chapter 8 of the present study), The Reluctant Fundamentalist proved to be a compelling film, demonstrating that Nair’s career as a filmmaker exploring and documenting South Asian diaspora life may be a book that has a few more chapters left to be written. Finally, in Queen of Katwe, Nair returned to her early cinéma vérité–influenced documentary realist technique, filming a group of slum children in the Katwe slums of Kampala as they learn chess from a devoted teacher. While box office returns were modest, this latter film has been a critical success, with many commentators celebrating its unique status as a Hollywood-financed film (Queen of Katwe was financed and distributed by Disney) set in Africa with an all-black primary cast.

Mira Nair’s Hybridity: Contextualizing a Postcolonial Filmmaker

Early in the process of writing the present book, the author approached the editor of a monograph series dedicated to film directors at a university press that shall remain nameless. When the suggestion of a title on Nair was put to the editor, the response was, “Probably not—she’s a little too Hollywood for us!” This response is understandable but mistaken. While Nair is certainly more mainstream than classic auteurs like Jean Luc-Godard or Francois Truffaut, a close viewing of her major films leads us to conclude that Mira Nair can and should be understood as a distinctive film author; her direction is visible in all of her films, including the early documentaries as well as her more recent work. That said, in this study I will not refer to Nair as typically an “auteur” in the manner of classic film criticism in the vein of Andrew Sarris and others. For one thing, while auteurist film criticism since the 1960s has tended to emphasize independence from commercial film studios (see Sellors 2010: 20), Nair has made some of her recent films commercially, where her directorial independence has sometimes been limited—though she has also continued to make smaller, independent films that bear the strong stamp of her creative signature. But there are a number of other good reasons to maintain a distance from auteurist theory for this particular study. First, a wave of feminist film theorists has since the 1970s been interrogating the male-centric and intensely exclusivist tendency of early auteur theory (see Mayne 1990: 95), though recent critics such as Geetha Ramanathan (2006) have nevertheless come to rework auteurism from a feminist perspective, positing a “feminist auteur.” Another comprehensive critique of auteurist film studies comes from C. Paul Sellors, who, in Film Authorship: Auteurs and Other Myths (2010), demonstrates the many slippages in this model of film analysis, including the significant fact that even the canonical film auteurs made their films collaboratively and under constraints associated with film studios and distribution systems. In his study Sellors suggests that symptomatic analysis of the works of film auteurs might be insupportable. Rather than using criticism of films to divine the mysterious motives of their authors (auteurs), Sellors suggests we might be better served thinking of film authors as the “causes” of the films they produce (Sellors 2010: 2); the task of the critic is, consequently, to interpret the films as visual and narrative texts. An engagement with directors is still relevant for Sellors as part of the critical process, but in a much more constrained and less absolute way than was the norm in the classic auteurist film criticism of the 1960s. As Roland Barthes might put it, we are not looking for the Author-God behind the curtain, but rather using a set of analytical tools by which to interpret (filmic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Mira Nair’s Diaspora Vérité

- 2. “Our Hearts and Eyes Are Wide Open”: Mira Nair’s Documentaries

- 3. The Aesthetics of Disillusionment: Salaam Bombay! (1988)

- 4. A Tale of Two “Chunaris”: The Critique of Bollywood in Monsoon Wedding (2001)

- 5. Into the Diasporic Mixing Bowl: Mississippi Masala (1991), The Perez Family (1995), and My Own Country (1998)

- 6. Feminist Period Pieces: Vanity Fair (2004) and Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996)

- 7. “Every Day Since Then Has Been a Gift”: The Namesake (2006)

- 8. “I Had a Pakistani Once”: The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2013) and Nair’s Post-9/11 Short Films

- 9. “Where Do You Belong?”: Returning to Uganda in Queen of Katwe (2016)

- Mira Nair’s Filmography

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Films of Mira Nair by Amardeep Singh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.