SEVEN

I WAS CONCEIVED IN Buenos Aires, in 1933. Think tango, clinking glasses, marital rows, chunky chandeliers and a 90-metre skyscraper (the tallest residential building in the city, only just completed), “El Safico” on number 456 Avenida Corrientes, “the street that never sleeps.” Here, on the twentieth floor, my future parents settled after staying in Santiago in the thirties, when the consulate in the Dutch East Indies was all but shut down because of the economic crisis. From this skyscraper, they had a spectacular view of the city and its picturesque skies, under which the street, at the speed of public transport and the accelerated revolving doors that gave entrance to the shops, propelled trade for those with money and even faster for those with none who were attracted by the hope of getting some: the prostitutes, pimps and other poor wretches that featured in the resounding tangos.

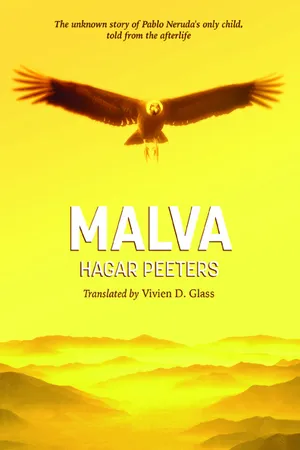

Up there, my father-to-be caught wistful evening glimpses of the sunsets he had described in his first collection of poems, Crepusculario. Looking out from his tower room on Maruri Street in Santiago de Chile, where he lived as a student, he had captured (this was years before meeting my mother) the most magnificent evening skies, threaded with golden rays of sunlight, woven through with yellow mist, shreds of orange and a dull red luster.

Now, the most flamboyant of sunrises and sunsets were again taking place behind the window panes, stirring no other emotion in my future mother, according to him, than one that drew loud oohs and aahs from her, as if taking her cue from him, confirming him in his awe instead of feeling it herself.

Stay out of my emotions, he said in his mind, where he also compared his own, melancholy, soul to a carrousel in the twilight and hers to a swing at an ordinary funfair. He had already stopped trying to hide his marital problems, though he sometimes half-heartedly kicked them under the carpet, only for them to peek out again the moment visitors arrived. Irritated, he went down the twenty flights of stairs to venture into the throng on nocturnal Corrientes. That’s where it all happened, that’s where his friends were waiting, where there were bars, the tinkling strumpets wearing their – to his mind – wonderfully sultry bells; and the moment he arrived at the ground floor, hands in his coat pockets, heart beating in the cool rhythm of the taxis’ horns, he felt the world boil in his blood. At the bottom of the stairs, having descended into the underworld, my future father arose from his personal death.

But she, whom his friends called his carabinera, police woman, always made him come home on time. The stern northerner (of Dutch descent), sturdy and draconian, waited up for him, carpet beater and sharp tongue at the ready. It was her own choice to stay behind in the ivory tower at night, though he was the one who made her wait for his return. The street was too far down to make him out in the crowd. All she saw after he left was a mass of anonymous dots; one of them had to be him, she knew. From down below, words floated up (after the tango by Homero Expósito and Domingo Federico):

THE SORROWS OF CORRIENTES STREET

Street, straight as a stream

cadging cash for crusts of bread

Avenue running through

the city like a vale of dread,

how sad and pale

are all your lights!

Your pillars and signs

sighing bright.

Your billboards

flashing cardboard smiles!

Laughter that comes after

courage found in alcohol.

Sighs, melodic lies

that sell us sweethearts for a song.

Jumble sale of sad delights

where caresses are traded

and illusions thrive.

Miserable? Yes…

because you’re ours.

Sad? Yes…

because you dream.

Your joy is sadness

and the pain of waiting

courses through you…

and makes you wither

in the pale light!

Gloomy? Yes…

because you’re ours.

Sad? Yes…

you’re down and out.

Slobs, whose only job is

posing as bohemians,

amigos with no pesos

just the dream of going far

that keeps them going,

drinking coffee

at a table in some bar.

Street, straight as a stream

cadging cash for crusts of bread

Avenue running through

the city like a vale of dread

where you were sold by men

and betrayed like Christ

and where the Obelisk’s dagger

forever bleeds you dry.

He always came home at unpredictable hours, always late at night when she, unable to sleep, would still be waiting. Tossing and turning in the heat, stewing in her loneliness. Locked up in that tower with only the skies for company – surrounded by fantasies, fata morganas, illusions and, far down below, the will-o’-the-wisp lights indicating the places he spent his evenings in the company of so many other women.

Everything happened there, and she was stuck here. Oh, the jealousy! He didn’t even try to hide it, came barging in with lipstick smudges still on his cheeks, a different scent at his throat every time, hairs on the shoulders of his disheveled jacket. Still drunk and roguishly cheerful, he would fling his clothes over the back of a chair as she lay in bed watching him. The woman lying on her side like a sculpture, nude and frowning, head resting on one arm. Poor mummy, he thought, dressed in your shroud, lying in your coffin. Do I have to sleep beside to you tonight, in the stuffy tomb you have made of our marital bed?

The next morning, he could hide behind his desk, escape into his consular duties, take refuge in his poems, pop outside for a cup of coffee, until later, in the evening, the evening…

She could do what was expected of a woman on a day like that: there were plenty of windows to clean, as many as twenty-eight of them looking out on all sides of the apartment, and she watched the strings of vinegar water zigzagging across the skies as if savagely crossing out his twilights.

Their record player lamented (after the tango by Carlos César Lenzi and Edgardo Donato):

And everything happens at dusk,

which magically conjures up love,

at twilight comes the first kiss,

at twilight, the two of us…

And everything happens at dusk

like a sunset on the inside.

How velvety soft it is

the dusky half-light of love.

One day, he brought home a girl. Her name was María Luisa Bombal, a young actress with literary aspirations whom they had met back in Santiago, where she had made a suicide attempt after being dumped by her lover. My father and mother, both getting broody, had befriended her with parental tenderness and invited her to stay with them at their Buenos Aires apartment until she got back on her feet. And now she had arrived.

“Look who I’ve brought along!” he who would be my father shouted delightedly from the hall that morning. “Our new mongoose,” and he pushed the young actress ahead of him down the hall toward my mother standing in the kitchen, and she exclaimed excitedly over her shoulder, “María Luisa! She made it!” and still clutching the tea towel, she trotted happily toward the girl and almost smothered her in a somewhat rigid embrace that was meant to express her joy and hospitality with Argentinian vivacity but didn’t quite succeed in masking her Nordic bashfulness.

María Luisa beamed when she saw the view of the good skies on all sides, and stepping into the kitchen, said in wide-eyed, delighted amazement, “What a beautiful, large table!”

“All the better for writing on,” my future father growled.

“And what a beautiful marble floor,” cried María Luisa ecstatically.

“All the better for thinking on. The white marble is veined with grey, like paper covered in handwriting. That corner over there is where I put my manuscripts. Over here at this table leg, the sheets of discarded lines of poetry flutter down when I’m writing, I hope it won’t disturb you. You can write as much as you like while you’re here. May this environment be an inspiration to you.”

“Yes. Yes!” María Luisa exclaimed. It all seemed even more beautiful to her than she had imagined from the novels. “I’m sure it will! It will,” she cried girlishly (at thirty-three summers old, she didn’t look a day over twenty). I have to admit she was very beautiful, with her symmetrical features, large brown eyes the color of hazelnuts, straight fringe and well-defined eyebrows. My father was already envisaging scenes of nocturnal discussions of their respective work (late at night when my future mother Marietje would be fast asleep) taking place at that table. His hand on her wrist while he whispered advice close to her ear, “You should rewrite that sentence like this, and oh, there’s a comma too many over here.” On her knee, “Well done, my girl, you’re very talented!” But María Luisa, who could spot advances coming centuries beforehand (as she put it in a metaphor that delighted my future father), determined that each should choose their own side of the table, divided by a watershed, and pointing at the flower vase in the middle of the tabletop, said (with mock sternness), there, the flowers marked the dividing line, and my soon-to-be-father shook his head with an equally feigned good-natured laugh at what he saw as that endearing, enraging, child-like cunning of hers.

She outsmarted him at every turn. He was no match for her lightning mind. Finally admitting defeat, he threw his hands up in the air in exasperation, put her on a pedestal, cajoled her along with throw-away remarks over his shoulder to his writer friends, where he introduced her as the only woman he had ever met with whom he could have a serious discussion about literature. María Luisa archly cut short such songs of praise: “You look for mothers in your lovers, but not all of us are suitable for motherhood.”

My almost-mother was standing next to her, only glad she was able to understand the Spanish. She took all the compliments paid to her guest in her stride, knowing she couldn’t hold a candle to her anyway, that she herself was at a double disadvantage: the cruel, ir...