- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Global health issues transcend national borders and state sovereignty. As a result, a collective response at the international level is necessary to effectively address these problems. This response, however, is not simply based on medical expertise or technology, but is largely dependent on politics. Health has become inextricably linked to policies developed by global governance, whether these policies involve the surveillance and the prevention of the spread of infectious disease across borders, the distribution and consumption of goods that pose a health risk through international commerce, the right to quality health for everyone, or the protection of human health from climate change and environmental degradation.

International relations theories provide a key analytical tool for understanding the dynamics of the political process in global governance in addressing health issues in an increasingly globalized world. Each chapter will features boxes highlighting case studies relevant to the material, discussion questions, and suggested readings.

International relations theories provide a key analytical tool for understanding the dynamics of the political process in global governance in addressing health issues in an increasingly globalized world. Each chapter will features boxes highlighting case studies relevant to the material, discussion questions, and suggested readings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Governance and Public Health by Geoffrey B. Cockerham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

International RelationsChapter 1

International Relations Theory and Global Health

On December 6, 2013, a two-year-old boy, named Emile Ouamouno, who lived in a remote village in southern Guinea became seriously ill and died four days later. Over the next few weeks, his mother, sister, and grandmother also died with similar symptoms. The disease soon began to spread outside of the village, crossing over into the neighboring states of Sierra Leone and Liberia. The cause of these deaths was not identified as the Ebola virus until March 2014 as fifty-nine people had died in Guinea by the end of that month (McNeil 2014). Until this point in time, the Ebola virus had been a rare, contagious disease that had mostly been confined to remote areas of Central and East Africa. After the first Ebola outbreak in 1976, 1,590 people had died from this virus (Sack et al. 2014). Nevertheless, it was not until early August 2014, when the World Health Organization (WHO) designated the epidemic as a “public health emergency of international concern.” While the WHO faced a good deal of disparagement from critics due to its slow response, at the same time, it “was never intended to be a ‘first responder’, but rather the ‘directing and coordinating authority’ in international health” (Kamradt-Scott 2016: 405). The following month, the United Nations (UN) Security Council declared the outbreak to be a “threat to international peace and security” (United Nations Security Council 2014). This action was supplemented by the United Nations General Assembly’s decision to direct the Secretary-General to establish the UN’s first emergency health mission (United Nations General Assembly 2014). Then in October, the WHO’s Director-General Margaret Chan called the outbreak “unquestionably the most severe acute public health emergency in modern times” (Cumming-Bruce 2014). By the end of 2014, 7,905 people had died from this outbreak (Reuters 2014). While almost all the cases of the disease were located in the impoverished countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, the disease managed to spread globally, including cases in the United States and Europe.

The 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa demonstrated how globalization has facilitated the spread of infectious diseases, including unusual and deadly diseases such as Ebola, from a small village in Guinea to two nurses in Dallas, Texas, in a matter of months. Because such diseases cannot be confined to national borders, some measure of global governance is often necessary to stem the growth of the problem. This need is especially strong when epidemics, such as Ebola, originate in poor countries that lack the capacity to efficiently diagnose, control, and treat these diseases. The puzzle regarding global governance in health, or any other area for that matter, is what is the appropriate arrangement for effective governance at the global level, and is sufficient political will to support such an arrangement available in a world structured around independent, sovereign states?

Although global governance in the area of health has undergone some significant changes since 2000, it is by no means a new area of international cooperation. A series of international conferences and treaties were concluded in the nineteenth century to promote interstate cooperation and standardization of procedures to contain the spread of infectious diseases. These diseases are products of nature that are not constrained by national borders. As European powers began to establish more networks around the world as part of their colonization process, such arrangements contributed to the spread of diseases on a global scale. Europeans brought new diseases, such as smallpox, to the Americas, resulting in the deaths of a significant part of the native population. Diseases such as cholera and the plague spread from Asia to other parts of the world killing millions of people. International cooperation to control the spread of these diseases was based on pragmatic interests rather than idealistic principles. During the nineteenth century alone, leading national governments conducted ten international conferences and negotiated eight agreements toward this end. By 1923, these states had also agreed to create two international organizations and one regional organization devoted to health. The extent of this activity in global health made it one of the most active areas of international cooperation during this time (Fidler 1999). The spread of disease is related to globalization. Because disease is a global phenomenon, states have had to continuously work together to manage this problem as the world has become more globalized.

Globalization is a complex process of integration on a worldwide level that affects people’s lives in a multitude of ways, including health. It is characterized by specific temporal, spatial, and organizational attributes that impact relationships globally. While globalization is not a new phenomenon, its post–Cold War form features an extensive reach of global relations and networks exhibiting high levels of intensity, velocity, and impact on many aspects of social life (Held and McGrew 2002). However, despite its increasing strength, it is not a uniform process as its effects vary throughout the world (Keohane 2001). That is, some locales are subject to greater degrees of globalization than others. Health is an important aspect of this development in that health and disease have been greatly affected by the pattern of contemporary globalization. The increased interconnections among states and people in the world have created a growing concern over a variety of threats to health that have transcended national borders and the jurisdiction of national governments (Cockerham and Cockerham 2010). At the same time, this process exhibits an inconsistent impact as certain health concerns and threats affect some parts of the world more than others.

A significant aspect of the globalization of health, as with the globalization of any facet of social life, is a lack of regulation. Globalization is not a normative concept in that it is neither inherently good nor bad, but it can exhibit both positive and negative influences on human life. Due to the lack of capacity of individual states to limit the impact of the negative aspects of globalization, some degree of cooperation, coordination, or regulation above the state level is necessary (Woods 2002). Determining the appropriate mode of governance is problematic, given the number of states and types of actors involved. Some scholars are pessimistic on whether globalization can effectively be governed. Rosenau (1990), for example, argues that a multicentric world has risen to challenge the traditional state-centric system that has previously dominated international relations. In particular, he views global governance as a disaggregated authority structure, where the spheres of authority, which are composed of many actors, are the main units of governance. The disaggregated nature of authority in global governance makes the coordination necessary for effective implementation unlikely (Rosenau 2005).

Despite the theoretical complexity of governance at a global level, the concept has received attention by policy-makers in the area of health. In September 2000, the Secretary-General of the UN, Kofi Annan, convened a summit of UN member states to adopt the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Endorsed by 189 states, these goals were translated into eight objectives that the UN member states agreed to achieve by 2015. Among these objectives was the goal of stopping the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and other major diseases, as well as improving child and maternal mortality. The achievements of the MDGs were mixed. On one hand, the number of people living in extreme hunger was reduced by millions, and the number of HIV/ AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis infections substantially declined since 2000. On the other hand, economic and gender inequality, as well as climate change and environmental degradation, still proved to be significant burdens for progress, especially for developing countries. Politically, however, the MDGs were viewed as a positive development, and the key principles maintained widespread support. During the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit held in September 2015, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted. The SDGs were designed to build upon the MDGs with a much more ambitious and comprehensive set of objectives.

Although the MDGs had a strong moral basis and universal political support in principle, their achievement by 2015 was questionable. With more ambitious objectives, the SDGs may face even greater obstacles. Different levels of socioeconomic development among populations and states, limitations on resources, distribution problems, conflicts of interests among relevant actors, and other issues pose significant obstacles that still need to be overcome. For global health governance to be effective, cooperation, coordination, and regulation issues need to be adequately resolved.

A limitation regarding the MDGs for global health governance was that they were primarily directed at infectious diseases. Chronic or non-communicable diseases did not receive the same level of attention. This relative neglect was taking place despite the fact that in developing countries, 80 percent more lives are lost to chronic diseases than infectious diseases (Mathers and Loncar 2006). UN-affiliated organizations like the WHO have also traditionally focused on infectious disease control rather than chronic disease control. This emphasis, however, began to change as with the WHO’s support of the passage of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003. Although the tobacco control movement was successful, other risk factors related to the causes of chronic diseases have yet to be addressed in a similar manner. For example, in the WHO’s proposed budget for 2018–2019, its top objectives were related to infectious diseases. A fund of US$805 million was allocated to reduce the burden of these diseases, with US$272 million for vaccine-preventable diseases, US$145 million directly for HIV/AIDS, US$124 million for tuberculosis, and US$116 million for malaria. In comparison, burden reduction for all non-communicable diseases was allocated US$351 million (World Health Organization 2017a).

The SDGs, however, provide much more comprehensive targets for global health than the MDGs do. In addition to calling for the end of the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria by 2030, the SDGs target a one-third reduction in premature deaths from non-communicable diseases and a substantial reduction in deaths from air, water, and soil pollution during this time frame. Objectives of the SDGs also include strengthening the implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and improving prevention and treatment of drug and alcohol abuse. Other significant health-related objectives encompass the achievement of universal health coverage, affordable access to essential medicines and vaccines, and a substantial increase in health financing by 2030. While the SDGs indicate even greater political support for global health in 2015 compared to that in 2000, the number and scope of these goals will be a substantial test for global governance.

Many issues are at the center of efforts to enact global health governance. In addition to the cooperation, management, financing, and regulation issues, health care coverage is at stake. Science and law are integral parts of this system, as they act to frame various issues for negotiations. In order to describe, explain, and understand global governance in health or any other area, theories of international relations can be useful tools in attempting to analyze such complex system. Why are international relations theories necessary to improve our understanding of global health? Global health issues transcend national borders and state sovereignty. As a result, a collective response at the international level is necessary to effectively address these problems. This response, however, is not simply based on medical expertise or technology but is largely dependent on politics. Health has become inextricably linked to policies developed by global governance, whether these policies involve the surveillance and the prevention of the spread of infectious disease across borders; the distribution and consumption of goods that pose a health risk through international commerce; the right to quality health for everyone, regardless of a person’s country of residence; or the protection of human health from climate change and environmental degradation. International relations theories therefore provide a key analytical tool for understanding the dynamics of the political process in global governance to addressing health issues in an increasingly globalized world.

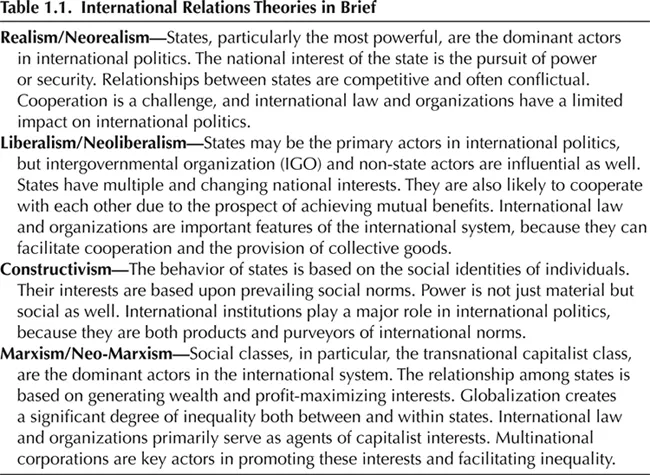

In its analysis of global health and global health governance, this book will focus on the dominant theories in the study of international relations, realism, and liberalism, as well as two of the leading perspectives outside of the mainstream in constructivism and Marxism. While this focus certainly does not nearly cover every theory of international relations, it does include an analysis of rational approaches (realism and liberalism), as well as its critiques from non-rational (constructivism) and critical theories (Marxism). In this chapter, I will discuss these influential theories of international relations and describe how they relate to the concept of global health governance as background reference material for the other chapters discussing key actors and topics in global health. A brief synopsis of each theory can be found in table 1.1.

REALISM

Realism is the oldest school of thought in international relations studies. It is a paradigm that is associated with several different theories, but the fundamental commonality is a state-centric view of international politics that assumes that the power and security interests of states drive the system. The roots of realist thought can be traced back to Thucydides, an ancient Greek historian, who wrote about the conflict between Athens and Sparta in his History of the Peloponnesian War during the 400s B.C. (Thucydides 1972). His account revealed a series of interactions among Greek city-states based on power politics and security concerns as motivating factors. Morality was defined by the powerful, and their will was imposed upon weaker entities, by force if necessary. This view of political realism reappears in the work of Niccolo Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Realism became integrated with the study of international relations with the work of E. H. Carr and Reinhold Niebuhr who challenged idealistic principles in international affairs. The most significant contribution in the early development of realism in international relations was Hans Morgenthau’s seminal text, Politics among Nations, originally published in 1948. This book was the first effort to specifically advance realism as a theory of international politics (Wohlforth 2008). Morgenthau’s approach, also associated with classical realism, established some influential assumptions about the nature of international politics. His theory assumed that politicians were rational decision-makers, whose actions are guided by the pursuit of power. States were the dominant actors in international relations, and international politics was a struggle for power among these actors. Decision-making and behavior were driven by rationality rather than by universal moral principles (Morgenthau 1967).

Neorealism emerged as a new interpretation of these ideas in the later part of the Cold War. Waltz’s (1979) Theory of International Politics sought to refine realism’s theoretical framework. He focused on the structure of the international system as a primary factor in understanding international politics. This structure consisted of two characteristics. The first is that the international system is based upon anarchy, which means that no central authority exists above the state. The second characteristic of the structure is the distribution of the material power capabilities among the states in the system. Due to a lack of a world government, the condition of anarchy has been a constant feature of international politics. The distribution of power, however, has varied over time as the system exhibited multipolar, bipolar, and unipolar characteristics at different periods in history. According to neorealism, the structure of the system constrains the act...

Table of contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Boxes and Tables

- 1 International Relations Theory and Global Health

- 2 Intergovernmental Organizations and Global Health Governance

- 3 Non-State Actors and Global Health Governance

- 4 Controlling Infectious Diseases: Malaria, Tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS

- 5 Securitizing Global Health

- 6 The Global Politics of Chronic Diseases

- 7 Health as an International Human Right

- 8 Global Health and the Environment

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author