eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

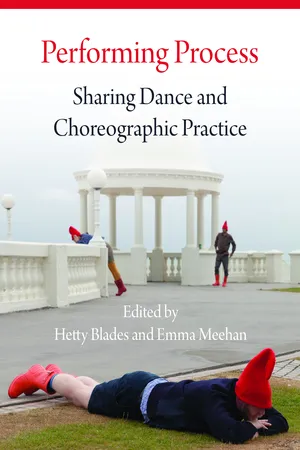

Performing Process

Sharing Dance and Choreographic Practice

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Performing Process

Sharing Dance and Choreographic Practice

About this book

Increasingly, choreographic process is examined, shared and discussed in a variety of academic, artistic and performative contexts. More than ever before, post-show discussions, artistic blogs, books, archives and seminars provide opportunities for choreographers to explain their particular methodologies. Performing Process: Sharing Dance and Choreographic Practice provides a unique theoretical investigation of this current trend. The chapters in this collection examine the methods, politics and philosophy of sharing choreographic process, aiming to uncover theoretical repercussions of and the implications for forms of knowledge, the appreciation of dance, education and artistic practices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Performing Process by Emma Meehan, Hetty Blades, Emma Meehan,Hetty Blades in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Philosophy of Process

Chapter 1

Atomos EChOs and the Process-ing of Dances

Stephanie Jordan and Anna Pakes

In the spirit of today’s autobiographical scholarship, this chapter on choreographic creative process is organized to reflect the creative processes of its authors. It begins, as Stephanie Jordan began, with a reflection upon Wayne McGregor’s Atomos (2013), which in turn stemmed from a research project (EChO) funded by the AHRC and hosted by the research wing of McGregor’s company Random Dance (now re-titled Company Wayne McGregor). EChO entailed studying the process of making Atomos, while situating this study within the context of an exhibition about McGregor’s creative practices across his career. Jordan’s original reflection ‘Atomos EChOs (2013)’ was published online in 2015. Haunted by the theoretical issues prompted by this writing (which appears here in revised form as Section 1), Jordan invited Anna Pakes to join her in further discussion of the philosophical and analytical implications of a widespread interest in choreographic process. Their collaborative writing forms Section 2 and 3 of this chapter. Section 2 surveys a broad range of creative process documentation that exists within dance, focusing upon twentieth-century, and particularly contemporary UK, practice, also highlighting today’s discursive turn and the influence of digital technology upon the proliferation and nature of this documentation. Section 3 examines a set of questions about artistic intention, audience understanding and the nature of dances, drawing from analytic philosophy and from genetic criticism and sketch studies within musicology.

Section 1: Atomos (Stephanie Jordan)

Atomos was made for Wayne McGregor | Random Dance, the company with which the choreographer has undertaken his most radical ‘research’. A piece for McGregor’s own company is an opportunity for more fundamental enquiry and reflection than most of his outside commissions offer. My memories of Atomos come from seeing two performances at Sadler’s Wells Theatre. As the title suggests, this is a piece inspired by the concept and structure of the indivisible atom itself.

It is significant that the context in which I saw Atomos was different from that of most premieres that I attend. I was part of the team on the AHRC-funded project1 called EChO (acronym for Enhancing Choreographic Objects), which refers to the concept of a choreographic (digital) tool, or rather agent, that can be used in the making of choreography. The word ‘Enhancing’ recognizes McGregor’s previous work with an autonomous, thinking, choreographic entity. Linked with the creation of Atomos, the new project was directed by WM|RD’s Research Director Scott deLahunta and company anthropologist James Leach.

I had been invited specifically as an advisor to the core EChO team, because of my interest in links between dance and science, here, however, to draw from dance studies (alongside Sarah Whatley from Coventry University). Being an advisor meant that I knew about the history and development of a new digital agent and the plans to present it to the public within the Wellcome Collection exhibition ‘Thinking with the Body’, down the road at Euston and running in tandem with the Wells performances of Atomos.2 The exhibition was as much about the longer history of McGregor’s fascination with science, since interdisciplinary discussions began back in 1999, a ‘Software for Dancers’ workshop in 2001, then initial explorations through artificial intelligence expanding into cognitive science in 2003, when McGregor became a research fellow in the University of Cambridge School of Experimental Psychology. The work ranged from analysis of thinking through the conventional tool of dancers’ notebooks, to the evolution, from 2008, of the first digital tool, the Choreographic Language Agent (CLA, deLahunta 2009). It is crucial, however, that those behind both the old and new agent were not simply software programmers but digital artists in their own right, Marc Downie (OpenEndedGroup, USA) and Nick Rothwell (Cassiel, UK).

The new agent was called ‘Becoming’. McGregor had pronounced: ‘The CLA needs a body’.3 The original agent had been fed by text that he and the dancers had provided, and, as stimulus for dancing, it fed back to them as moving geometry on screens at the side of the dance studio. The dancers danced, went over to peer at the screen, danced again: they stopped and started and got cold. The CLA was lifeless. ‘Becoming’, on the other hand, emerged from a rectangular, human-size screen, so it bears some of the characteristics of an eleventh dancer in the studio. A skeleton of lines like bones intersecting with joints appears out of nowhere, and appended to it are what look like light webs, hairs, as well as arrows and geometrical structures. Wearing 3-D glasses, you notice how it can rotate and trace luscious arcs. Thus, it elicits a kinaesthetic response, as if alive. This is one in a series of ‘moves’, each followed by blackout, during which the ‘creature’ prepares for the next move. Sometimes a joint that has ‘grown’ a cluster of bones presses directly towards you, dispassionately. The effect is calm, sometimes sinister, sometimes juicy, cooler if the colour is blue, more dangerous if it is red or shot through with yellow. McGregor thought it beautiful....

There was a big secret behind this creature, namely its origins within the well-known science-fiction film Bladerunner (1982, using Ridley Scott’s director’s cut). McGregor kept quiet about the identity of the film until a public interview prior to the second performance of Atomos, but it shaped the creation of the CLA. Downie and Rothwell set about dissecting the film into frames, 1200 in total – McGregor refers to this process as the film ‘cannibalising’ itself. They proceeded to analyse the motion in each shot digitally and create software that would respond autonomously to that motion in a series of responses (the number code of frames and moves is revealed at the base of the screen). ‘Becoming’ can make decisions, retain certain diagrammatic and mechanistic qualities, but also appear human, contending with gravity and incorporating the semblance of intention. It operates with rules that you see across the top of the screen, about 25 in total, like ‘Adds Stiff Angle’ and ‘Parachute’, or the ‘muscle’ annotations, ‘Torque’, ‘Torque Pair’ and ‘Linear’. Downie, who has worked in the past with Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown, has spoken of the invention as ‘attempting to be beautiful, evocative, invidious, but simultaneously transparent...’ and, significantly, drawing attention to, and declaring, its own processes. Hopefully, he says, it ‘trains your eye to see how it’s made’.4 This already gestures towards a general purpose that reflexive attention to process is thought to serve: it provides a kind of guidance or perceptual training for viewers; it enhances appreciation of the choreographic product or, indeed, of the complexity and interest of the process itself. Section 2 offers further critical discussion of that idea.

But, as in Cunningham’s seminal work (greatly admired by McGregor), the application of computer technology also drives artists towards discovery, as choreographer and dancers are constantly surprised and forced into new directions. In turn, choreographer and dancers donned their glasses. ‘Grab a frame and it provides a series of propositions’ says McGregor.5 So they selected frames of ‘Becoming’ that interested them, and set about gleaning from it movement information that would transform their personal vocabularies.

A film of this working process by David Bickerstaff was the brilliant climax of the Wellcome exhibition, footage of ten Random dancers (who are creative movement-makers themselves) engaging with an eleventh companion projected blown up across a far wall. We sat on benches watching this wonderful piece of theatre, having already experienced ‘Becoming’ live and with the glasses, in an ante room. It was here that I got to know this creature privately. On my second visit, I sat looking at it for an hour or so.

Atomos had featured earlier in the exhibition at the end of a timeline detailing McGregor’s career with science. Here, I found the PACT project (Process and Concept Tracking) especially intriguing, an analysis of McGregor’s creative thinking by cognitive scientist Phil Barnard across six interviews spread between May 2012 and October 2013. We saw highlighted the pathway of the choreographer’s decisions about Atomos through time, what changed, what ideas came and went, when, how and why, in other words the messy process of artistic creation. Through this anatomization of creative impulse, we learnt that ‘Becoming’ was at one point intended to appear on stage, before it found its home in the studio.6 We also read that McGregor approached the creation and fixing of structure and movement content in a new way. This was less about creating a body of movement and then developing and structuring it into a whole piece, which he had done in the past, more about the generation and structuring of material running in parallel, the choreographer leaving each short ‘atom’ alone, not to be revisited or revised until a much later distillation process.7 On film, McGregor indicated that he found Barnard’s methodology during interview very useful to his future work, suggesting that (at least in this case) self-conscious understanding of process enhanced creativity.8 I was eager to know more about how these discussions might impact on his future, and whether they had already affected his process during the making of Atomos itself.

The entire ‘Thinking with the Body’ exhibition was geared towards artistic process, telling us about McGregor’s own experience but, in some instances, getting us to look at our own perceptual behaviour. We were invited to see sound (Ben Frost’s score for McGregor’s previous work FAR [2010]) in a darkened room, and to engage with an installation designed by Magpie Studio to bring into 3D Random’s 2013 learning resource book for school teachers called Mind and Movement – Choreographic Thinking Tools.

The exhibition experience encouraged me to consider my own process, or route through, the larger project of Atomos. This was as follows: observations of three rehearsals in North London (two of these creative workshops, the third a run-through of existing material, although I was not lucky enough to see ‘Becoming’ in action at any of these, and many late rehearsals were closed to visitors); two long visits to Wellcome; two public interviews with McGregor (at Wellcome and Sadler’s Wells); a further Wells seminar at which the whole AHRC-EChO ‘Becoming’ team was present; the premiere and second performance of the work itself; finally brief email correspondence with Odette Hughes, Associate Director of Random Dance. More than I can possibly know, that order of events, in no way precisely engineered, greatly influenced the kinds of ideas and perceptions that I had at different stages of Atomos’s development. Apart from the Wells performances themselves, I simply happened upon, picked up on, information that became available along the way. (N.B. It was not possible for me to have any discussions with the dance artists prior to the premiere.)

Very early on, I was struck by the size of the crowd of collaborators working both inside and outside the studio. Not only was there McGregor (responsible for concept, direction and set) and the Random dancers, but also those involved with design, Lucy Carter (lighting), Ravi Deepres (film and set photography), Studio XO (costumes) and the composer duo A Winged Victory for The Sullen. There were also the scientists and researchers, with their computers and cameras, all of whom were to feature at Wellcome and who, as Barnard put it, were invited to ‘help him [McGregor] to break his conventions [...] to improve his creative thinking’.9 As well as Barnard and deLahunta, there was David Kirsh, from University of California, San Diego, developing his Distributed Cognition project, which tracks the transmission and ‘growing’ of ideas between McGregor and his dancers (through both language and motion) while, from a social science perspective, Leach (now Professor at the University of Western Australia) led a discussion workshop for McGregor and dancers – on the concept of the human body as collectively owned and produced.

Soon, I noted a particular vocabulary shared between the choreographer and his scientists, terms used like ‘sonification’, ‘attentional score’, ‘pixillation of movement’. Soon too, I learnt from deLahunta that everyone involved in the creation of Atomos was asked to watch Bladerunner, and to ‘atomize’ it (deLahunta 12 August 2013 interview). Some had liked the film, some not, yet it had a significant effect upon the ‘feel’ of the new piece and its structuring, especially the violence of its cutting. From a range of interviews, I understood that there were still further stimuli, for instance: biometric data (such as temperature, retinal movement, adrenalin flow, stress arousal) which came to be termed ‘body broadcasting’, although these could give rise to intimate, secret passages of dance; grids, drawn from the algorithmic work of Josef Albers; prime numbers (another concept of indivisibility); and that McGregor had created a series of 31 separate dance ‘atoms’. Hughes informed me that three of these dance ‘atoms’ were derived closely from ‘Becoming’. No. 26 Becoming/Text comprised solos and duets that drew direct...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Philosophy of Process

- Part 2: Methods and Formats

- Part 3: Documentation, Dissemination and Scores

- Part 4: Politics and Labour

- Contributors

- Index