- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

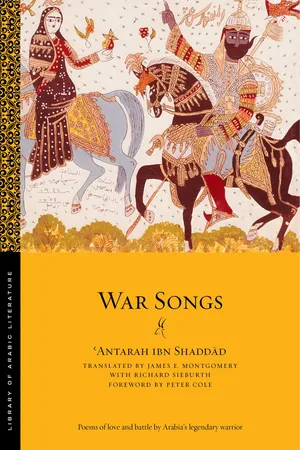

Poems of love and battle by Arabia's legendary warrior

From the sixth-century highlands of Najd in the Arabian peninsula, on the eve of the advent of Islam, come the strident cries of a legendary warrior and poet. The black outcast son of an Arab father and an Ethiopian slave mother, 'Antarah ibn Shaddad struggled to win the recognition of his father and tribe. He defied social norms and, despite his outcast status, loyally defended his people.

'Antarah captured his tumultuous life in uncompromising poetry that combines flashes of tenderness with blood-curdling violence. His war songs are testaments to his life-long battle to win the recognition of his people and the hand of 'Ablah, the free-born woman he loved but who was denied him by her family.

War Songs presents the poetry attributed to 'Antarah and includes a selection of poems taken from the later Epic of 'Antar, a popular story-cycle that continues to captivate and charm Arab audiences to this day with tales of its hero's titanic feats of strength and endurance. 'Antarah's voice resonates here, for the first time in vibrant, contemporary English, intoning its eternal truths: commitment to one's beliefs, loyalty to kith and kin, and fidelity in love.

An English-only edition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Letter from the General Editor

- About this Paperback

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- A Note on the Text

- Maps

- Notes to the Introduction

- Al-Aṣmaʿī’s Redaction

- Two Qasidas from Ibn Maymūn’s Anthology

- Poems from The Epic of ʿAntar

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Notes

- Glossary

- Concordance of Principal Editions

- Bibliography

- Further Reading

- Index

- About the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute

- About the Translators

- The Library of Arabic Literature

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app