![]()

1

9/11 as Horror

In his article for The Nation, ‘9/11 in a Movie-Made World’, Tom Engelhardt argues that the United States has cinematically imagined ‘9/11’ long before it happened (2006: 15). Our cinema has presented the destruction of New York, of the United States and of the world many, many times. When such a visual catastrophe did occur, multiple commentators observed that it was ‘like a movie’. Cinema taught us how to perceive, receive and understand the events unfolding that day (on a screen, for most observers). Conversely, the images of that day were immediately iconic, many (but not all) repeated endlessly in the days and weeks that follow, and continue to be presented publicly each anniversary of the attacks.

As noted in the Introduction, however, Hollywood has by and large eschewed presenting images of 9/11 itself directly. Instead, the images and experiences have been distanced and displaced into genre narratives. Just as the ancient Athenians no longer allowed historical representation in the theatre of Dionysus, but filtered their fears, hopes and social dramas through mythic subject matter, so, too, does the United States explore 9/11 through the fantastic, the monstrous and the horrific. This chapter is in two parts. The first part considers the tropes and images of 9/11 and how horror films have appropriated them. The second part offers brief readings of three films that have reproduced 9/11 as a horror film in different ways and offering different understandings of the meaning of that event: War of the Worlds (2005) and Cloverfield (2008), which write 9/11 as large horror, and Mulberry Street (2006) which reproduces it as smaller, personal horror. All three films present New York as a site of horror.

Part 1

Iconic elements, images and tropes

Several elements, tropes and images dominate post-9/11 horror. No one film has all of the elements and images and no image or trope appears in every film. But together these elements represent ways in which horror cinema has appropriated 9/11 and its imagery, not least of which in order to contain it, understand it and re-experience it under safer conditions or with a different ending.

First is the idea of New York City as ‘ground zero’, a term usually associated with nuclear destruction. The city itself was not destroyed, but the imagery of destruction and the specific images from that day of deserted streets, and conversely larger crowds fleeing, combined with gray ash, dust and debris covering everything and everyone and the overall picture of New York was of a city in ruins. ‘Ground zero’ also indicates the heart of an attack. New York had always been a site of horror in cinema, as noted in the Introduction, but 9/11 made it the site of horror.

Until 9/11, Los Angeles was the preferred city to destroy in American culture. Mike Davis reports that between 1952 and 1999, Los Angeles was destroyed in novels and films an average of three times every year, far more than New York or London, the next two most destroyed cities (1999: 276). Since Hollywood is solipsistic, Hollywood is also one of Hollywood’s favorite targets. Los Angeles is prominently featured in films of global destruction, even if not the primary setting of the film.1 Yet, after 9/11 it is New York that becomes the site of primary destruction, death, mayhem and attacks. New York is 9/11, in a way the other sites are not. I have heard anecdotally from New Yorkers of tourists asking ‘where 9/11 is’, referring to the footprints of the Twin Towers. Linguistically, this question indicates not only that 9/11 is now perceived as a place, not an event, but that the place it is located is solely the province of Manhattan. Nor is the Pentagon or the field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania referred to as ‘ground zero’. 9/11 has a hierarchy: New York is where 9/11 happened; the Pentagon and United 93 are secondary sites in the public imagination. As a result, New York is the centre of post-9/11 horror.

Figure 1.1 Although set in Los Angeles, Skyline features a shot of New York City’s skyline burning with the Statue of Liberty in the foreground. After 9/11, New York is the central site of horror.

I do not suggest that New York was not a primary setting for horror before 9/11 (it most certainly was) nor do I suggest that all post-9/11 horror is set in New York (it is not: it takes place all over the United States and the world, in both urban and rural settings). I do argue, however, that New York has gained primacy as a site of horror in a way that it was not before the terror attacks. Even films whose original narrative is set elsewhere find a home in post-9/11 New York City. The novel The War of the Worlds is set primarily in London; the 1953 film is set primarily in Los Angeles; but the 2005 film is set in New Jersey, New York and the road to Boston. The 1954 novel I Am Legend is set in Los Angeles, the film The Omega Man is set in Los Angeles, the 2007 I Am Legend is set in New York. Even films such as Skyline, all but a few minutes of which are set in Los Angeles and specifically in Marina del Rey on L.A.’s Westside, cannot resist a shot of the Statue of Liberty and the skyline of New York City under attack by the same aliens (see figure 1.1). While the film-makers ostensibly do so to show that the entire nation, if not the world, is undergoing the same attack, it is interesting that no other city is represented. M. Night Shyamalan’s film The Happening is set primarily in Philadelphia and rural Pennsylvania, but it opens with mysterious suicides in Central Park and at a construction site in New York City. When the United States is attacked, New York is attacked, even if the film’s focus is on a different locale. New York also serves as a locale for every type of horror. Although ‘hillbilly horror’ is better suited to the South or the West, films such as Stag Night (2008) relocates it to the New York City subway system.

The image of New York burning, or attacked or on fire is therefore one of the first and most iconic images to emerge out of 9/11. The attacks were experienced as images long before they were understood as information. Writing in the New York Times, C. James confessed, ‘the images were terrifying to watch, yet the coverage was strangely reassuring because it existed with such immediacy, even when detailed information was scarce’.2 On the day itself, we were overwhelmed with lots of images and underwhelmed with little information, only mostly speculation. The images themselves, however, were frightening, evocative and have since been employed to reconnect to the terror of the day itself. Iconic images include planes crashing, crowds fleeing, buildings being destroyed, walls covered in photos and fliers of the missing and the dead, empty streets and falling bodies, evocative of ‘The Falling Man’.

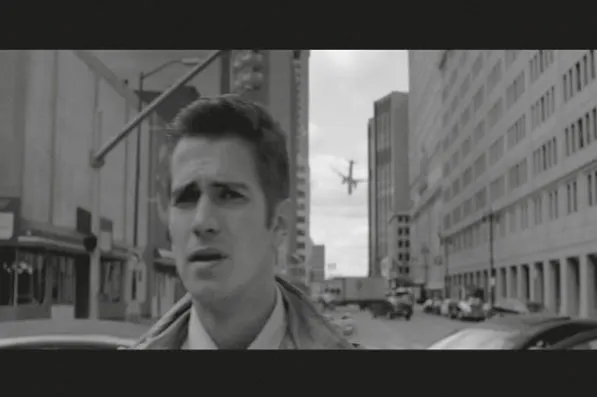

Figure 1.2 In Vanishing on 7th Street, as Luke emerges from his apartment to a deserted street, a plane crashes to the ground behind him.

Planes crash in films in which the crash of the plane is not integral to the plot. Knowing (2009) shows a plane on approach to Boston’s Logan Airport (where two of the 9/11 flights, American Airlines 11 and United 175 originated) crashing into a field next to a gridlocked highway. Vanishing on 7th Street shows a plane crashing into a deserted and windswept city street (see figure 1.2). Pulse (2006), the American remake of the Japanese film Kairo (2001), recreates an image from the original, a plane in flames passing low over the protagonists before crashing behind city buildings, an image made all the more stunning and relevant in the American version (see figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 A plane in flames flies low over the heads of the protagonists before crashing into city buildings in Pulse, an American remake of the pre-9/11 Japanese film Kairo.

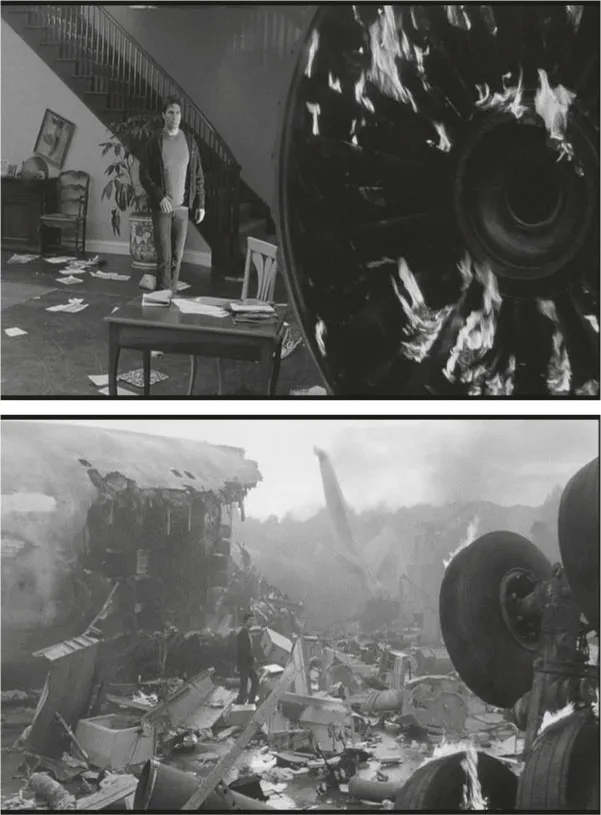

Steven Spielberg’s controversial War of the Worlds, which will be explored in greater detail below, literalizes a metaphor for the experience of 9/11. Working class everyman Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise) hides with his children in the basement of a upper middle class suburban home for safety while journeying from New Jersey (another 9/11 flight origin point) to Boston. During the night there is a huge crash and destruction above their heads, which the film implies may be the aliens attacking in their tripods. In the morning, Ray emerges from the basement to literally find a crashed jet in the living room. He slowly enters the destroyed space to see a jet engine on fire in the living room (see figure 1.4). Just as the constant stream of images on September 11 literally brought the image of the second plane crashing into the South Tower into American’s living rooms (and offices, and bedrooms, and kitchens, etc.), Spielberg has crashed a plane into a suburban living room. As Ray emerges through the hole in the house to see the rest of the crashed fuselage outside, we see that the entire neighbourhood is unrecognizable from the images of the previous night (see figure 1.5). The only thing visible is smoke and wreckage, nothing else, nothing ‘normal’ can be seen. The crashed plane is in the living room, and it has changed the world forever. We might read this single image as THE visual metaphor of Spielberg’s film.

Figure 1.5 9/11 literalized: the crashed plane in your living room in War of the Worlds.

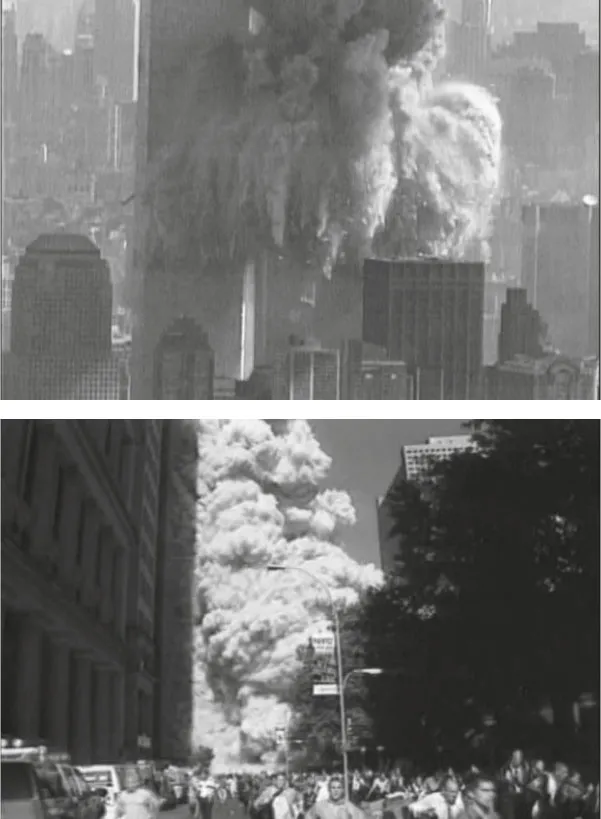

Spielberg has said that for him the unforgettable visual of 9/11 was ‘the image of everybody in Manhattan fleeing across the Brooklyn Bridge’ (quoted in Gordon 2008: 253). Although we have seen images of crowds fleeing before, from War of the Worlds (1953), Independence Day (1996), Gojira (Godzilla, 1954), and numerous disaster films, the image changed in two ways on 9/11. First is the transformation in the nature of the image itself. The crowds fleeing in the above-mentioned films run past a static camera. Crowds move past a camera that is capturing the image, but is separate from the events itself. As a result of much footage from 9/11 coming from cameramen and women who were running themselves, a very different crowd-fleeing scene has risen to prominence: flashes of a fleeing crowd combined with unrecognizable images as the person holding the camera runs (see figures 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8). As one can see from the images from Cloverfield and War if the Worlds, crowds now flee not past the camera, but with it, creating a jarring, shaky series of images echoing the camera work of 9/11.

Also echoing the images of that day is the slow-moving crowd. Both War of the Worlds and Cloverfield feature this second changed image – the slow migration of large numbers of people away from city centres on foot. They are not running, but they are moving en masse. The Happening also shows this image, albeit writ small, as Elliot Moore (Mark Wahlberg) leads a small group from Philadelphia out to the suburbs and then rural Pennsylvania on foot. In all three of these films, the slow-moving, walking mass of humanity treads through or across familiar landmarks, and then begin to run when confronted with new threats. In Cloverfield, the crossing of the Brooklyn Bridge is recreated in the film, just before the creature then attacks the bridge, causing the crowd to panic and begin running.

Figure 1.6 From Inside 9/11, a cameraman flees along with a crowd, looking back at the smoke cloud behind them. The moving camera offers a very different fleeing crowd image than before.

Figure 1.7 From Cloverfield, the crowd flees as does the camera, held by Hud.

Figure 1.8 1.8 From War of the Worlds, the crowd flees the initial attack, the camera moving with them.

Figure 1.9 and 1.10 From National Geographic’s Inside 9/11, the collapse of the South Tower, the iconic cloud of dust and debris as the building sheds materia...