![]()

Part 1

Re-examining Disney

Chapter 1

Disney Authorship

Introduction

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is one of Disney’s most iconic animated sequences. It tells the story of an impetuous apprentice – Mickey Mouse – who seeks to use his master’s magic to make his domestic work easier. After seeing the sorcerer leave for bed, Mickey dons his master’s hat, interpreting it as the source of his powers, and proceeds to bring a wooden broom to life. Having done so, Mickey then instructs the broom to fill the basement’s basin with water from an outside fountain; witnessing the broom’s mastery of this task allows Mickey to relax, which quickly sees him fall asleep. However, while he rests, the broom continues to fill the indoor basin until it begins to overflow. Panicking, Mickey tries, ineffectively, to stop the broom, eventually attacking it with an axe. Unfortunately, the broken splinters become new brooms that, in turn, form a water-carrying army which relentlessly fills the basement with water. As Mickey floats upon the Sorcerer’s spell book, frantically searching for an incantation to stop the brooms, his predicament becomes increasingly perilous as a whirlpool begins to pull him beneath the surface. At this moment the Sorcerer appears at the basement entrance. Gesturing, he parts the water and descends. With the water receding, Mickey bashfully returns the magic hat to his master and continues with the housework by hand.

Most viewers would probably identify Mickey Mouse as the sole perpetrator of this chaos. Such a response, however, reveals the difficulty of studying authorship. Romantic notions of authorship, such as William Wordsworth’s definition of poetic authorship as a ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ (1984, 598) recollected in tranquillity, no longer offer a satisfactory account of the authorial process. Roland Barthes’ essay, ‘The Death of the Author’, provides perhaps the most famous counterpoint, arguing that a ‘text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture’ (1995, 128). Although Mickey may be the most visible authorial force in the aforementioned sequence, this belies the numerous converging factors that both support and are shaped by his vision – most notably the broom, the hat and the Sorcerer.

Disney’s role in the ‘authorship’ of his animated features is no less complex. As Sean Griffin notes, ‘Walt Disney so successfully performed authorship of his studio’s output during his lifetime that many customers thought Walt drew all the cartoons himself’ (2000, 141). Worryingly, this oversimplified appreciation of Disney authorship can still be seen today, perpetuated, as noted in the Introduction, through internet forum posts and similarly critically unregulated spaces. If we return once more to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, it is possible to view the short allegorically, representing specific tenets of Disney authorship: Mickey reflects Disney’s desire to innovate, to find new ways of producing animation; the broom, a paragon of hard work, which, in its fractured state, becomes an efficient work force, symbolizes the hierarchical evolution that occurred at the Studio as Disney pursued an industrialized model of cartoon production; the hat, emblematic of the Sorcerer’s magic, functions much in the same manner as Disney’s name, serving to prime audience expectation; and lastly, the Sorcerer, a figure of power, mirrors Disney’s omniscience during his Studio’s ‘Golden Age’. Given this complexity, it will be useful, in this opening chapter, to detail how ‘Disney’s’ authorship evolved during his stewardship, and to explore the possibility that other figures within the Studio might hold competing claims to authorship of ‘Disney’s’ animated features.

Authorial Evolution

Clearly, Disney constitutes a rather unconventional authorial figure. The collaborative nature of film, which in recent years has come to represent the biggest challenge to the auteur concept, is even more pronounced when discussing feature animation. In addition to the compartmentalized nature of animation production, in which hierarchically and topographically separate artists work towards a unifying goal, the Studio, by 1935, ‘had more than 250 employees’ (Barrier 2008, 110). However, this vision of Disney production, which problematizes a simple attribution of authorship, is reconciled by Disney himself: ‘I think of myself as a little bee. I go from one area of the Studio to another, and gather pollen and sort of stimulate everybody . . . that’s the job I do’ (Schickel 1997, 33).

Central to this ‘bee’ analogy is Disney’s disengagement from the actual physical act of animation, which had been a facet of Disney production since the late 1920s. Disney has himself remarked on this transition:

This was how Disney functioned for the majority of his stewardship, operating as, to borrow Paul Wells’s definition, an extra-textual auteur; while Disney did not draw the key frames and in-betweens, or even ink the image, he was the ‘person who prompt[ed] and execut[ed] the core themes, techniques and expressive agendas of a film’ (2002b, 79). The production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) provides a good example of this type of authorship in action.

Michael Barrier observes that although ‘Disney had started the year planning to direct Snow White himself . . . he was by the fall of 1936 delegating to [David] Hand a supervisory role over the whole of Snow White’ (1999, 212–13). Given that much was resting on Snow White’s ability to return a profit, the election of Hand to effectively direct the project was a calculated decision. Hand ‘approached the director’s job in the spirit of a business executive, farming out detail work . . . to subordinates and concentrating instead on broader issues, which at the Disney studio entailed primarily an intensive reading of Walt Disney himself’ (Barrier 1999, 134). Barrier uses ‘reading’ as a way of alluding to Hand’s need, and ability, to gauge how best to please Disney. However, Hand’s proclivity towards a broader level of control over Snow White, and his reluctance to involve himself in the daily artisanal tasks of the project, resulted in certain aspects of the film becoming fragmented.

One such issue revolved around how the dwarfs were to be realized. While it had been common practice in the years leading up to Snow White for animators to be assigned a particular character to animate (for example Art Babbitt’s animation of Goofy), this appropriation of resources was impractical given the scale of Snow White and the numerous overlapping characters. Hand once remarked, with reference to the dwarfs, ‘There were so many of the damn little guys running around, and you couldn’t always cut from one to the other . . . We had to cut to groups of three and four, so it became a terrific problem of staging’ (Barrier 1999, 244). Early in 1936 Hand came up with an alternative to the one-animator-to-one-character model, breaking the animation down, more or less, by sequence. To combat the lack of continuity inherent in this procedure, Hand called for ‘each dwarf [to have] obvious mannerisms, so that they would be recognisable even in the least accomplished animation’ (Barrier 1999, 214). Babbitt, however, argued against such superficial mannerisms as a way to define character, calling for animators to adopt a Stanislavskian mindset: ‘You have to go deeper . . . You have to go inside – how he [the character] feels’ (Barrier 1999, 214). Ultimately, the solution to this conflict came via live action. By filming actors (and Studio staff) to form unique character ‘maps’ for each dwarf, when individual animators were called to animate a particular dwarf, they had a quick reference point, which could refresh the specific mechanics of that character.

While this situation was effectively resolved by a handful of the Studio’s more senior personnel without Disney’s direct intervention, this belies the authorial influence he did exert. This can be seen, first and foremost, in the fact that continuity of appearance was such an important issue. Disney’s insistence on carefully planned scenarios and industrially executed animation constitute key predicates on which Snow White was made, and an absolute insistence on continuity is one of the most visible ways in which Disney’s animation differs from earlier examples of ‘straight ahead’ animation (see Chapter 2). Secondly, and perhaps most significantly, the key animators’ awareness of Disney’s instance on believability would have guided them, as Babbitt remarked, to get ‘inside’ the dwarfs’ minds. This insistence on ‘verisimilitude in . . . characters, contexts and narratives’ (Wells 1998, 23) during the production of Snow White effectively established the blueprint for what would become the Disney-Formalist style (see Chapter 3) –a style that dominated the Studio for several years.

Given that Disney’s name now connotes and promotes much more than just squash-and-stretch animation, Wells has also argued that the ‘Disney’ name be redefined ‘as a metonym for an authorially complex, hierarchical industrial process, which organises and executes selective practices within the vocabularies of animated film’ (2002c, 140). This appropriation of ‘Disney’ is a particularly appealing one considering the persistence and mutability of Disney’s authorship, beginning in the 1920s, running throughout the ‘Golden Age’, and continuing after his death in 1966. Furthermore, ‘Disney’ has become a signifier for a particular way of reading ‘a film, or series of films, with coherence and consistency, over-riding all the creative diversity, production processes, socio-cultural influences and historical conditions et cetera which may challenge this perspective’ (Wells 2002b, 76). In this sense, Disney serves as a trigger, priming the audience to expect a specific style of animation, be it produced during the ‘Golden Age’ or more recently, during the Studio’s Renaissance period (see Chapter 6).

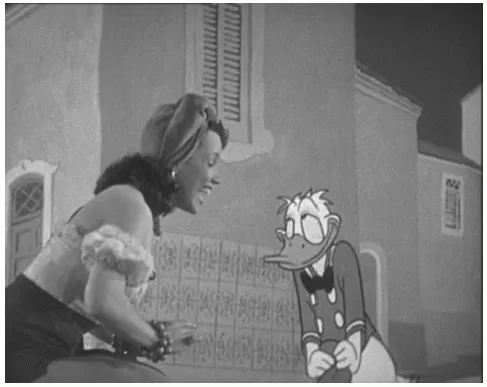

This interrogation of the complexities of Disney authorship, and the industrial processes that support it, provides a welcome alternative to Marc Eliot’s troubling and controversial account of Disney authorship. At his most progressive, Eliot proposes a romanticized notion of Disney authorship, positioning Disney at the centre of all filmic meaning – a version of authorship far removed from that of the cross-pollinating bee, whose main responsibility is to unite the creative individuals who are physically responsible for the finished animation. Taking The Three Caballeros (1944) as an example, Eliot sees the film’s colourful aesthetic and amorous Donald Duck (Figure 1.1), as ‘the most vivid representation yet of Disney’s raging unconscious’ (2003, 180). Most alarming, however, is how Eliot’s account ignores the social context in which the film was produced – a factor which would have had a definite influence on the film’s animators.

FIGURE 1.1 An amorous Donald Duck.

Ultimately, Eliot sees The Three Caballeros as a direct reflection of Disney’s own personal feelings and mental state, pointing to how, during the production of The Three Caballeros, ‘[John Edgar] Hoover was feeding Walt a continuous stream of information regarding the possibility of his Spanish heritage’ (2003, 180). Eliot argues that at the ‘same time the true facts of his birth were being investigated, Disney “gave birth” to Donald Duck, in many ways Walt’s “second-born” and Mickey Mouse’s antithetical “sibling” ’ (2003, 180, emphasis added). Eliot even goes so far as to interpret the Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck characters in a psychoanalytical context:

Eliot concludes that Disney’s decision to ‘retire’ Mickey Mouse for The Three Caballeros had less to do with market demand, and more to do with Disney’s personal emotions: ‘Mickey’s absence may have signalled the breakdown of Walt’s fragile emotional balance, projected in the emergence of an unleashed Donald, the sexually provocative, libidinous duck, who thumped with desire for all make and manner of unattainable Spanish women’ (2003, 182).

By contrast, Esther Leslie comments, with reference to the production of The Three Caballeros: ‘The loss of [stylistic] unity is symptomatic; that is to say, it is true to the epoch. The film reflects the deep bewilderment of the time, a time of war. Disney comes yet again to be a symptom of the crisis of culture, and the crisis of the social world, yet this time negatively, without hope. Disney is absorbent of the prevailing energies’ (2004, 291). While the precise sociohistorical conditions highlighted by Leslie would undoubtedly have coloured the animator’s artistic choices at this time, other, more pragmatic, influences would also have had an impact on the collaborative process required to produce such a film.

Given the obvious attraction, yet inaccuracy, of such accounts of Disney authorship, Wells’s redefinition of Disney as metonym provides an essential, industry-centred paradigm through which to interpret Disney authorship. While Wells observes that Disney is ‘an auteur by virtue of fundamentally denying inscription to anyone else, and creating an identity and a mode of representation which, despite cultural criticism, market variations, and changing social trends, transcends the vicissitudes of contemporary America’ (2002b, 90), he does not seek to recover the authorial claims of those subsumed by the Disney name. Instead, his multi-purpose redefinition serves to ‘prioritise an address of the aesthetic agendas of the Disney canon in preference to ideological debates’ (Wells 2002b, 85).

However, Disney’s investment in the authorial process changed throughout his life, ranging from his well-documented omnipotence during the Studio’s ‘Golden Age’, to a more reticent involvement through the late 1950s and up until his death in 1966. His authorial commitment during the earlier period is particularly evident in a series of memos sent in June 1935. As Barrier notes, Disney sent these ‘memoranda to thirteen of his animators, criticizing their work individually’ (2008, 112). One animator, Bob Wickersham, received the following comments:

Such micromanagement, representative of Disney’s own bee analogy, contrasts starkly with his involvement in the Studio’s animation from the mid-1950s onwards. In the years following World War II, ‘Disney’s interest in animation waned as he increasingly turned his attention to live-action movies, nature documentaries, television, and the planning of his innovative amusement park’ (Watts 1995, 95). Moreover, Barrier observes:

This disengagement had a profound effect on Disney’s attitude towards his Studio’s short animation. No longer was he concerned, above all else, with the quality of his art; now his priority was quantity. Confronted with the realities of television scheduling, Disney drew a startling analogy: ‘Once you are in television, it’...