![]()

Part One

Transatlantic Modes of Production

![]()

1

Come Back to Erin: Themes of Exile and Return in the “O’Kalem” Films

Peter Flynn

It’s a thick black room and a rough

rude crowd—the real strong human

stuff—

A screen’s before, a beak of light rules

through the air—enough!

Lo, on that beam of light there darts

vast hills and men and women,

The screen becomes a stage; here Life,

blood-red with the living human!

In but ten minutes how we sweep the

Earth, unbaring life,

Here in Algiers and there in Rome—a

Paris street—the strife

Of cowboys swinging lariat ropes—the

plains, the peaks, the sea—

Life cramped in one room or loosed out

to all Eternity!

Yea, in ten minutes we drink Life,

quintessenced and compact,

Earth is our cup, we drain it dry; yea,

in ten minutes act

The lives of alien people strange, the

Earth grows small; we see

The humanness of all souls human; all

these are such as we!

From The Nickel Theatre by James Oppenheim

Introduction: Life cramped in one room

The above lines, taken from the American poet and novelist James Oppenheim’s 1907 celebration of the nickelodeon, acknowledge one of the primary attractions of America’s first modern democratic art form—its ability to bring the vistas of the world and its strange inhabitants to the “rough, rude crowd” who made up the lion’s share of early motion picture goers.1 For Oppenheim, the nickel theatre linked the worlds of the urban poor in cities like New York with those of faraway lands, eliminating space and distance. But the majority of early cinema audiences were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, and so the distant landscapes that unspooled before them were not always so foreign nor the peoples they depicted so alien. Indeed, for many, the flickering screen of the nickel theatre brought images not of the strange or exotic, but of home—of the familiar lands that want and persecution had compelled so many to leave.

This essay explores the representation of Ireland and the Irish in American cinema from the early-to mid 1910s and addresses the way these representations spoke to, and for, the Irish in America. By 1910, the Irish were becoming upwardly mobile, steadily assimilating into the American mainstream. Their nationwide campaign against demeaning “stage Irish” stereotypes, waged in the first decade of the century, was a highly successful assertion of the newfound confidence that increasing fortune and influence had brought about. Starting in the 1840s, when the first significant waves of Irish began arriving in the United States, mainstream nativism had sought to bar their entry into genteel society. But by the early 1900s, anti-Irish sentiment was on the wane and “lace-curtain” respectability was finally within reach.

Nevertheless, despite their new success and social mobility, the Irish in America were unwilling to break with their heritage. Memories of the homeland remained strong. Anti-English sentiment and support for Irish home rule were significant factors in Irish America’s continued interest in Ireland, but so too was nostalgia for the simpler pre-modern community of rural Ireland from which the vast majority had come. Fantasy images of slow-paced pastoral plenty and close-knit rural communalism functioned as a buffer against the demoralizing effects of tenement life which the Irish has first experienced in America and continued to exert a calming influence in a world marked by urban over-crowding, inter-ethnic tensions, and dehumanizing industrial progress.

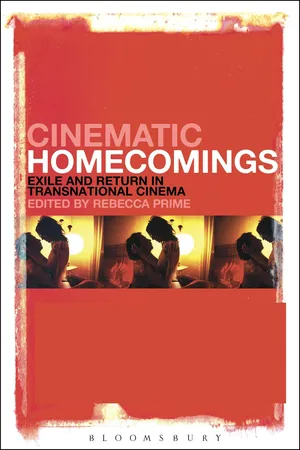

Figure 1.1 The O’Kalems in Ireland.

Few filmmakers realized this more than Sidney Olcott and Gene Gauntier. Working initially for the New York-based Kalem Film Company and then later as independents, Olcott and Gauntier produced a series of films in Ireland between 1910 and 1914. Dubbed the “O’Kalems” by the contemporary press, Olcott and Gauntier are unique in early film history. Not only did they make a series of unprecedented filmmaking excursions across the Atlantic to Ireland, but they also represented the people and culture they found there with an honesty and sensitivity rare for the ramshackle cinema of the Nickelodeon era. The Lad from Old Ireland (1910) was the first of the O’Kalem films, as well as the first American film shot outside the Americas, and quite possibly the first fiction film to be made in Ireland. Its success led to the production of more than two-dozen others—a mix of rebel dramas, folk romances, transatlantic dramas of emigration, and non-fiction travelogues extolling the virtues of the Irish countryside and its people.

These films offered a surprisingly nuanced and authentic picture of Irish life in the 1910s and reflected the layered, often contradictory characteristics of immigrant and native-born Irish culture in America. They spoke to the traumas of exile and the twin histories of poverty and political persecution that led many to leave their families and communities. They spoke also to the excitement and opportunities the New World offered Irish-born immigrants—to the possibilities for upward mobility and assimilation into the American mainstream. Most importantly, the “O’Kalem” films offered a new and unique cinematic mythology for the Irish in America—a grand narrative of exile and return; of moving forward into the New World without abandoning the Old; of the creation of a trans-Atlantic hyphenated culture, capable of changing the destinies of both host and native lands.

These narratives were played out with melodramatic aplomb in the films themselves, but also in the ways in which they were made and promoted. And while their appeal extended to include all immigrant groups as well as native-born Anglo-Saxons, they were told specifically for the Irish in America. Indeed, for the Irish in those nickel theaters, it wasn’t just the great global expanse that was cramped in one room, but the new and the old, the living and the dead, the nightmare of history, and the great American dream of the future. The genius of Sidney Olcott and Gene Gauntier lay in their recognition of this. Their films in Ireland collapsed the gulfs separating the Old World from the New. They gave meaning to the painful experiences of emigration and helped ease the pangs of exile. Indeed, their films offered the possibility of a cinematic homecoming (to borrow the title of this collection), or (to paraphrase Denis Condon) a form of virtual tourism wherein viewers could return to the homeland, revisit familiar sites and people, simultaneously holding the film as both the journey home and a souvenir (or relic) of the visit.2

The fact that Olcott and Gauntier were themselves tourists of a sort—charmed by the quaint beauty of the surroundings, irritated and bemused at the lack of modern amenities—underscores this notion of virtual tourism. Indeed, while their films work to celebrate many aspects of rural Irish life (particularly its communal values) they nonetheless hold firm the belief that the New World is superior. For the Irish in America, this was by no means off-putting for it suggested that they had made the right decision in emigrating; that their exile was not in vain; that the freedom and mobility they lacked in Ireland would be provided by America. In short, the O’Kalem films offered Irish immigrants the opportunity (unavailable to most in real life) of going home, revisiting their past, then returning to America, reassured in the knowledge that Ireland, however quaint and beautiful, could never provide them with the opportunities available in America.

In this sense the O’Kalem films present themselves as a fascinating case study in early immigrant spectatorship and the pre-Hollywood cinema’s representation of race and ethnicity. To date a significant amount of work has been done in this field. The publication of Miriam Hansen’s Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Cinema in 1994 set a wealth of scholarship in motion.3 Hansen offered a critical context for understanding early cinema audiences as heterogeneous spectators, whose encounters with the pre-Hollywood cinema was determined by their specific cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds. Work like Judith Thissen’s essay on Jewish audiences in New York in the early twentieth century, or Giorgio Bertellini’s analysis of Italian audiences, are representative of the scholarship that followed.4 By comparison, however, the work of the O’Kalems has received scant attention. In large part this is due to the commercial unavailability of the films. But the release in 2011 of The O’Kalem Collection, 1910-1915 DVD set has rectified this. Of the 30 or so Irish-themed titles produced by Sidney Olcott and/or Gene Gauntier in the 1910s, nine titles are currently known to survive in complete or partial form and are featured on the DVD.5

What follows here draws heavily upon the material in The O’Kalem Collection as well as the memoirs of Gene Gauntier, which chronicle her involvement in the American film industry from approximately 1907 to 1912. Entitled Blazing the Trail, the 225-page manuscript was completed in December 1928 in Stockholm and was heavily abridged for a serialized publication in the monthly Woman’s Home Companion from November 1928 to March 1929. For the most part I resort to the original Gauntier-typed manuscript (held at the archives of the Museum of Modern Art in New York), but at times various distillations offered in the publication make for more succinct and effective quotations. Other sources used include the film trade journal the Moving Picture World, the New York Dramatic Mirror, and Kalem’s in-house periodical, The Kalem Kalendar.

Blazing the Trail—to Ireland

The Kalem Film Company was founded in 1907 by George Kline, Samuel Long, and Frank Marion, whose surname initials (K, L, and M) gave the company its name. Kalem’s first employees were Sidney Olcott, hired as director and occasional actor, and Gene Gauntier, as scenarist and leading lady. Olcott and Gauntier gathered about them a small troupe of actors and began producing wilderness films, set in and around Fort Lee, New Jersey. The company quickly gained a reputation for location shooting and in 1908 they relocated their troupe to Jacksonville, Florida for the winter months—thus becoming the first New York film company to leave its home base for any extended period. In Florida they made a series of highly successful southern romances and civil war dramas—including The Girl Spy (1909) and The Cracker’s Bride (1909)—and would return there again in the winter of 1909–10....