![]()

1

The sway of America and Europe

In the mid-1920s, the young Hitchcock remained susceptible to the influence of other filmmakers, and over the next few years we can see his debt to certain American, German, and Russian directors emerging noticeably in his films. At the heart of this lay notions of film construction—how to build a shot in both space and time, and how to put shots together to generate the rhythm and tempo of the film. Not simply esoteric technical matters that filmmakers ponder, these were the essential elements of designing how an audience would respond, especially at an emotional level. Some of these directors spoke about their film techniques using musical terminology, not merely putting music forward as a simile but in fact as something actually tied to their procedures: Hitchcock did not hesitate to follow their lead. By no means did that influence come only from other filmmakers. As a young man interested in all the arts, regularly attending concerts and the theater, taking dance lessons, and reading avidly, Hitchcock found elements in all these activities that could be applied to filmmaking.

Edgar Allan Poe

One of the influences Hitchcock seemed most prepared to talk about was that not of another director, but of a writer, Edgar Allan Poe. In his essay “Why I Am Afraid of the Dark” he posed the question: “Was I influenced by Edgar Allan Poe? To be frank, I couldn’t affirm it with certainty. Of course, subconsciously, we are always influenced by the books that we’ve read. The novels, the paintings, the music, and all the works of art, in general, form our intellectual culture from which we can’t get away.”1 In this essay, first published in French in 1960, he says much about Poe and himself, and considering the French had been fascinated with Poe for over a century by that point, his enthusiasm may have been directed to the receptive audience of Arts: Lettres, Spectacles. Of course he gives us much more, including a short history of his reading of Poe, and perhaps most notable here is what he does not say about Poe’s effect on him. Starting with his early reading of Poe, he points out, “It was only when I was sixteen that I discovered his work. I read first, at random, his biography, and the sadness of his life made a real impression on me.” In the next few years he devoured Poe’s works: “When I would come back from the office where I worked, I would hurry to my room, take a cheap edition of his Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, and begin reading. I still remember my feelings when I finished ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue.’ I was afraid, but this fear made me in fact discover something that I haven’t since forgotten.” He also includes “The Gold Bug” among the works making a strong impression on him, and as Dennis Perry reminds us, neither this nor “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” appear in Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, suggesting he read Poe much more widely than the volume mentioned.2

Focusing mainly on fear, horror, and suspense, he answers with little hesitation the question about influence:

Near the end of the article he backs away from the comparison between himself and Poe, calling Poe a poete maudit, and himself a mere commercial filmmaker, although he certainly would not expect French readers to think of him in that way; they should fill in the blank, recognizing him as an artistic director. In broaching a more difficult comparison between himself and Poe, despite both of them liking to make people shiver, he concluded that Poe lacked a sense of humor: “for me, ‘suspense’ doesn’t have any value if it’s not balanced by humor.” Nevertheless, “Poe and I certainly have a common point. We are both prisoners of a genre: ‘suspense.’ You know the story that one has recounted many, many times: if I was making ‘Cinderella,’ everyone would look for the corpse. And if Edgar Allan Poe had written ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ one would look for the murderer.”3

Of course we can all see the connection between the two of them concerning fear and suspense, but the most important facets they have in common Hitchcock notes so briefly that they may pass unnoticed, and this lies in the two words “hallucinatory logic.” Normally one would not place these two words together, since one implies the opposite of the other, but for Hitchcock they get at two fundamental elements of his films and Poe’s writing, one having to do with the images that generate their aura and atmosphere, while the other, logic, considers the methods of control and construction to make them most effective. We do not know if Hitchcock read any of Poe’s theoretical writing, such as his “Philosophy of Composition” or The Brevities, but it seems entirely possible even if he had not that he could have intuited much of what Poe had to say about his writing. The parallels between Hitchcock and Poe in the area of construction have not gone unnoticed;4 both of them were calculating to the point of being mathematical in their approach to designing a work. In Poe’s words,

Hitchcock went in the same direction as a filmmaker, according to Truffaut “universally acknowledged to be the world’s foremost technician.” Perry backs this up with the observation that “his pre-cut productions are planned to the point that, as Hitchcock himself said, ‘I can hear [the audience] screaming when I’m making the picture.’”6 In later years Hitchcock would drive producers such as David O. Selznick to distraction by shooting his films with such precision that the producer/editor could do nothing with the takes other than what Hitchcock intended.

While some of Hitchcock’s own comments on construction from articles and interviews sound similar to Poe’s, the influence of Poe’s writing on atmosphere and emotion proves much more difficult to pin down; music possibly plays an important role here. Musical images abound in Poe’s writing, and Hitchcock would certainly have been aware of them, such as these from Ligeia: “enthralling eloquence of her low musical language,” or “by the almost magical melody, modulation, distinctness, and placidity of her very low voice.” In Loss of Breath he gives a subtitle “Moore’s Melodies,” or The Tell-Tale Heart has the line “I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations.” His fondness for this type of image may seem to be somewhat superficial, but in fact it points to something beneath the surface, the way in which music permeates his writing at the deepest possible level, the element that Baudelaire and the later French symbolists found so appealing about his works. In The Brevities Poe has much to say about the bearing of music on his writing, and while we have no evidence that Hitchcock ever read these essays, some of Poe’s ideas seem remarkably similar to comments made by Hitchcock or approaches he uses in his films.

A large number of Hitchcock’s films use the piano as a striking and ambiguous image, as Chapter 7 will make clear, sometimes seen and played, at other times seen and heard with no one actually playing it, and often seen but not heard. For Poe, “The great variety of melodious expression which is given out from the keys of a piano, might be made, in proper hands, the basis of an excellent fairy-tale. Let the poet press his finger steadily upon each key, keeping it down, and imagine each prolonged series of undulations the history, of joy or of sorrow, related by a good or evil spirit imprisoned within.”7 Here he discusses not only music for the piano with its melodious expression, but also the wave of sounds that can emanate from the instrument simply by holding down the keys, the instrument’s tone now becoming comparable to emotions or even an aura of good or evil. In fact, that aura appears trapped within the sound, but the sound can release it for others to experience, inciting the reader in a way that normal prose cannot. Poe’s piano works very much like Hitchcock’s organ noted in the Introduction, which allowed him, he claimed, to direct his viewers and play them, “like an organ.”8 He referred to this as a game with the audience, but it went much further, linking this musical image with construction and his ability to achieve the desired result with viewers.

In “Why Am I Afraid of the Dark” Hitchcock made much of Poe’s place in literature, calling him “without the shadow of a doubt, a romantic and a precursor of modern literature.” In placing him historically, he notes that Poe went to school in England “when Goethe had already published Faust and when the first stories by Hoffmann had just come out. This romanticism is perhaps even more apparent in the translation done by Baudelaire, which is the one you use.”9 Following this he links Poe and Baudelaire closely together, calling Baudelaire the “French Poe.” The details may not always be correct (part one of Faust had been published by 1818, but not part two) but the perceptions are interesting, including evoking the name E. T. A. Hoffmann. Hoffmann stood as one of the most influential of the early romantic German writers, and for him music played an essential role in his way of defining the essence of romanticism, something that came easily to him as a prominent composer as well as being a leading writer. That essential quality of music to romanticism for him lay in the capacity of music to find a level of expression not bound by fixed images, invoking a sense of the indefinite and even the infinite, a capacity he believed that words on their own lacked. For poets, according to Hoffmann, music became the best possible model for images, and poets should aspire to the state of instrumental music.

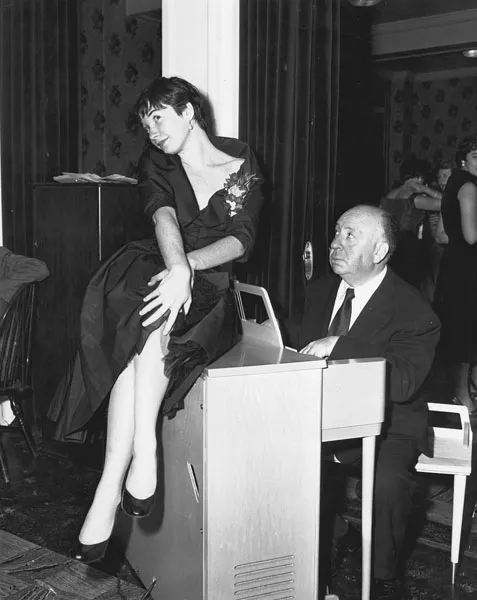

1.1 Hitchcock with Shirley MacLean (Directing from the piano)

In writing about Tennyson, Poe takes a position similar to that of Hoffmann’s, making this comment in relation to the “Lady of Shalott”: “If the author did not deliberately propose to himself a suggestive indefinitiveness of meaning, with the view of bringing about a definitiveness of vague and therefore of spiritual effect—this, at least, arose from the silent analytical promptings of that poetic genius which, in its supreme development, embodies all orders of intellectual capacity.”10 To understand this, one must switch to a discussion of music, and Poe does this directly, proceeding immediately with the following:

He rails at music which fails in this, singling out a late eighteenth-century piece by Franz Kotzwara, the Battle of Prague, laughing at “the interminable drums, trumpets, blunderbusses, and thunder.” Here he even gets into matters of orchestration, one of Hitchcock’s favorite musical subjects, although now he shows how ludicrous it can be if handled badly, becoming prosaically non-musical (blunderbusses and thunder). Music, he says, should not attempt to imitate anything, and if it does, that should be limited to what the Italian poet Gian Vincenzo Gravina believed possible, “to imitate the natural language of the human feelings and passions.”

After this discussion of music he returns to Tennyson, now to matters that could apply most directly to cinematography for Hitchcock: “Tennyson’s shorter pieces abound in minute rhythmical lapses sufficient to assure me that—in common with all poets living or dead—he has neglected to make precise investigation of the principle of metre; but, on the other hand, so perfect is his rhythmical instinct in general, that, like the present Viscount Canterbury, he seems to see with his ear.”12 Rhythm and meter for both Poe and Hitchcock lie at the center of their views of their respective arts, and Poe’s censure here exactly parallels Hitchcock’s own disparagement of other directors whose style he claimed he did not like, such as Cecil B. DeMille. Most striking though is Poe’s comment that Tennyson could “see with his ear” (his emphasis). Here lay the impulse that Hitchcock and Poe had most deeply in common, expressed by Poe in a way that sounds even more apropos to cinema than to poetry. The chapter which follows will attempt to get at this notion—how a film can be thought of as a symphony in a genuine way; the directors Hitchcock encountered in Germany revealed a large part of how it could be possible to see with the ear.

German expressionism

In an interview with Bob Thomas in 1973, Hitchcock recalled the years he spent in Berlin, and emphasized the importance of this experience to his future career—especially the film made immediately after his return: The Lodger. In his words, “in 1924 I went to Berlin. These were the great days of German pictures. Ernst Lubitsch was directing Pola Negri, Fritz Lang was making films like Metropolis, and F. W. Murnau was making his classic films. The studio where I worked was tremendous, bigger than Universal is today. They had a complete railroad station built on the back lot. For a version of Siegfried they built the whole forest of the Nieblungenlied.”13 Later in ...