![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Early Greek Cinema: 1905–1945

Constructing the Cinematic Gaze

ON NOVEMBER 29, 1896, ATHENIANS PAID A hefty price to attend the first ever screenings of moving pictures on Greek soil. The screenings took place nine months after the Lumière brothers officially patented their invention in Paris. At a central street in Athens and at a humble venue especially modified for the occasion, a strange inscription read: Cinematofotographe Edison. An anonymous reviewer wrote in the newspaper The City (To Asty):

Carriages are travelling, horses are running, the sea is quietly moving, the wind is blowing, clothes are waving, trains are departing, Ms Loie Fuller is shaking and twisting like a colourful snake her paradoxical, unique and famous clothes, so that one thinks that they have before them living human beings, faces enlivened by blood, bodies pulsating with muscles. The illusion of life, in all its endless manifestations, parades in front of us. When it becomes possible to have a series of Greek images, of Athenian scenes and landscapes, the cintematofotograph will then excel, becoming an even more enjoyable spectacle. However, even as it stands, it presents one of the most astonishing inventions of science, one of the most fascinating discoveries; it is worth being watched by everybody and, certainly, they will all watch it and immerse themselves in its consummate phantasmagorias.1

Every day for a month, 16 screenings were offered until Alexandre Promio, the representative of the Lumière brothers, took the projector and the short films to Constantinople. All famous early films made by the Lumières were screened: L’ Arrivée d’un Train, La Sortie des Usines Lumière, Lyon les Cordeliers, Le goûter de bébé, and others. Despite their immense success, no special interest in film was shown in the Greek capital for over four years. Adverse and disastrous circumstances at the beginning of the following year quashed any curiosity or entrepreneurial interest in further exploring or making use of the new invention. (The first screenings were organized in Thessaloniki, then under Ottoman rule, in July 1897; and, in July 1900, the first regular screenings were shown at the famous Orpheus theater on the thriving commercial island of Syros.)

Indeed, the new art of cinema was the casualty of the political and social upheavals of Greek history. In order to establish itself and consolidate its presence, the medium needed political stability, social cohesion, and, of course, peace with other countries: essentially the preconditions for the establishment of technological infrastructure and the development of a sophisticated studio system that would allow for the emergence of film culture. Such pre- conditions were absent from Greek history until 1950. Prolonged periods of warfare (1912–1922), political instability (1922–1928 and 1932–1936), dictatorships, failed coups, and ultimately the German occupation followed by the Civil War (1946–1949) deferred for almost 50 years the smooth incorporation of the technological infrastructure and the conceptual framework that cinema as an industry and as an art needs to flourish.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the nation state of Greece had a total population of about 2,500,000 people; another 3,000,000 Greeks lived outside the national borders, mainly in the Ottoman Empire, Russia and Egypt. Athens, the capital city, had an unremarkable population of 130,000 and competed with other established centers of Greek civilization, such as Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria, for cultural and financial domination.2 The Greek economy was predominantly agricultural, although in the last decades of the century several programs of international investment were in place and the presence of the working class had become noticeable in the political and ideological debates of the country.

In April 1896, Greece organized the first Olympic Games of the modern era. The success of the Games raised the hopes of the Greek people and the political establishment on many levels. However, by the end of 1897 the country experienced the effects of a humiliating bankruptcy, first announced in 1893 by the Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis (1832–1896) with one of the most memorable phrases of Greek political vocabulary: “Regretfully, we are bankrupt!” The bankruptcy was a long process and was the painful outcome of a combination of intense borrowing for infrastructure works, the systemic corruption of a state based on political clientelism, the organization of the Olympic Games, and, finally, of a humiliating military defeat by the Ottoman Empire in the so-called Black 1897 War.

Nonetheless, against all odds, the movement for a social and political renaissance began during the first decade of the new century, when the country was forced to confront the dilemmas of modernity and proceed with its industrialization process, its rising working-class movement, and its unresolved territorial disputes with the collapsing Ottoman Empire (mainly in Crete and Macedonia). Programs of reform were gradually implemented by different governments, starting in 1900 and culminating in the Goudi Uprising of 1908 when rebellious but ineffective officers demanded political concessions from the rather indolent and indifferent King George I of the Hellenes.

In this political and social climate, the Psychoule Brothers from the city of Volos, Thessaly, introduced the first projection machine to Athens in 1899 at the Varieté theater behind what is today the site of the Old Parliament, screening short films, which they later took to the countryside. In 1900, other entrepreneurs, especially those from Smyrna or Alexandria, like Cleanthis Zahos and Apostolos Kontaratos, imported new projectors and installed them at the cafés surrounding Constitution Square between the Palace and the Parliament. Fierce competition broke out between the café proprietors for the premiere screening of the most recent French and Italian productions.

The first movies, however, started being regularly screened at the industrial port of Piraeus by the Smyrnian businessman Yannis Synodinos. The initial session consisted of Edison’s The Battle of Mafeking and one of the great commercial successes of the day, Georges Méliès’ Cinderella. Other movies directed by Ferdinand Zecca and produced by Charles Pathé, such as Histoire d’un crime and Les Victimes de l’alcoolisme, became popular. Thanks to Pathé’s entrepreneurship, the tradition of Pathé-Journal with newsreels of actual events was to become the enduring legacy of early French cinema to Greek cinematography.

After 1904, many cafés imported their own projectors, and the desire of their proprietors to attract greater audiences to their establishments only intensified the antagonism between them. A number of newsreels were taken during the Greek-Turkish war of 1897 by Frederic Villiers (1852–1922) and by Méliès himself (1861–1938)—these have to be the earliest film recordings on Greek territory3. An unknown American cameraman first filmed Athens in 1904. Later in the same year, an enigmatic French cameraman, named Leon (or Leons), who worked for Gaumont, Pathé’s great competitor, came to Athens to cover the mid-Olympiad of 1906 and filmed the games. His films were among the first existing visual records made on Greek territory.

In 1907, an unknown cameraman made the first Greek journal, filming The Celebration of King George I. In 1908, a successful businessman from Smyrna, Evangelos Mavrodimakis, began to offer regular screenings of movies in the center of Athens, which had only just been supplied with electricity. On the central Stadiou Street he established the first movie theater, naming it the Theater of the World; he is considered to be the father of the Greek cinema venue.

In these early days, each session usually consisted of a screening of eight short films, accompanied by a pianist, with improvised melodies, but later, whole orchestras were added together with popular singers. In early 1911, the first permanent cinema, Olympia (to be renamed later Capitole), was built in Piraeus by Yannis Synodinos, thereby inaugurating the material infrastructure for the expansion of cinema on Greek territory.

It was not, however, until 1911/12, after the city of Athens was fully supplied with electricity, that three grand cinemas were specifically built to cater for the needs of the new art and its growing audience (Attikon, Pallas and Splendid). But open-air screenings retained their appeal for Athenian audiences, continuing the tradition of the open-air performances of the shadow theater of Karagiozis, which was for many decades the most popular form of public entertainment. In 1913, one of the most historic, almost legendary, cinemas opened in Athens, the Rosi-Clair, which was to screen the most popular films over a period of 50 years and which was finally closed down in 1969, under changed circumstances.

In subsequent years, the famous Pantheon theater was established at the center of the city for the middle class, while the more humble Panorama was opened in a less-auspicious suburb for the underclass. By 1920, a network of six cinemas existed in the capital, together with open-air screenings that continued to be offered by a considerable number of cafés. Throughout the country, with the annexation of the city of Thessalonica in 1912 and the rest of Macedonia and the Aegean islands, an overall number of 80 cinemas were in operation by the end of the decade.

During this period, due to the increasing demand for technological support, many foreigners were invited to Athens as cameramen, maintenance technicians, and projectionists. Some chose to stay. Among them, the German-Hungarian Josef Hepp (Giozef Chep, 1887–1968) worked relentlessly for decades to consolidate the new art form and should be recognized as one of the most prominent film-makers in the history of Greek cinema. Hepp was a man of artistic brilliance with a superb sense of style for mise-en-scène, and his contribution is worthy of closer study. He arrived in Greece in early 1910, after an invitation from King George and bearing the conferred title of “Royal photographer and cinematographer.” His first film was the short journal From the Life of the Little Princes, which he shot in early 1911 with the King’s very many children and grandchildren. He later recollected:

When I arrived in Greece, I fell in love with its lucid colors, its blue skies, the unembellished lines of its landscapes, but mostly with its people, their customs and way of living. I filmed them and I was the first who made images to represent Greece in other countries.4

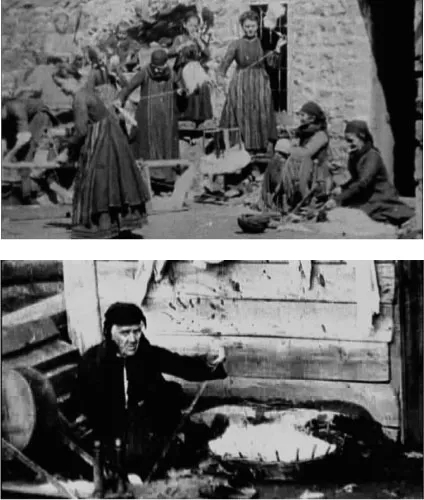

Meanwhile, in 1905 in Macedonia, the brothers Yannakis (Ioannis) (1878–1954) and Miltiadis (1882–1964) Manaki recorded rural scenes from the life of ordinary villagers.5 They made a number of reels, which established the genre of ethnographic documentary in the Balkans, despite their disputed political agenda. Macedonia was a contested area that still belonged to the collapsing Ottoman Empire, but Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria aspired to annex it to their national territories.

The Manaki brothers produced films that depicted the ethnic diversity of the region as well as the strange in-between minorities that had escaped the attention of the political rivals. These included work on the Aromanian Vlachs, Macedonian Slavs and the Romas. Christos Christodoulou has observed that, “The Manaki Brothers . . . recorded the Balkans at some of their most critical historical moments with both touching impartiality and a sense of documentary precision.”6 Within their work, films of special significance as the earliest visual records of an ethnographic nature from the region include Customs and Traditions of Macedonia (1906), The Visit of Sultan Mehmet V to Thessaloniki and Monastiri (1911), Turkish Prisoners (1912), Refugees (1916), and The Bombardment of Monastiri (1916).

These early short reels are still very close to photographs; they are indeed moving pictures, and their photographic stillness can be detected in the decades to come as their enduring artistic legacy to Greek cinema. Miltos Manakis had some interesting ideas regarding photography:

Photography is in essence an art form. We are artists/technicians of a sort, comparable to the painters of the past. They were not the only ones who could give beauty to what they painted; we do the same thing with our photographs. A good photograph depends on the play of light . . . And this is something only an artist can do, someone who knows what is attractive, divine and aesthetic . . .7

Manaki brothers, The Abvella Weavers (1905/6). Greek Film Archive Collection.

Indeed, one can readily discern the continuity between still photographs and the cinematic representations in Greece and the Balkans at the time. Local artistic practices were based on the great, long, and venerable Byzantine tradition of religious iconography. The visual language of perspective that had dominated European painting since the Italian Renaissance was totally absent from the cultural optics of the country and, certainly, of the whole of Eastern Europe. The new tradition of painting, dominant in the late nineteenth century, was predominantly imported (it was even named the “Munich School”), and was still struggling to find its specific Greek expression and style. (It is interesting, however, that in his pioneer essay on cinema, Vachel Lindsay refers to the paintings of the main representative of the Munich School, Nickolas Gyzis, when he talks about “mood” in the cinematic image of Mary Pickford.)8

The face in Byzantine icons and frescos is self-illuminated, without shades or shadows; and space is depicted symbolically not “realistically” or “naturalistically.” That which interests the Byzantine tradition more is not the story but the “organization of space” and how the viewer experiences its “psychic content.” Its point of view is located within the iconographic space and through the special pictorial practice called “inverse perspective,” according to which the image and each of its components gaze at the viewer and not the viewer at the image.9

Similarly, the camera works with the interplay between light and dark, and with space, in a realistic, photographic sense by juxtaposing patterns, shapes, and forms in order to generate emotions through visual contrasts. The struggle to create depth, to explore natural space, and to understand perspective as the contrast between grades of black and white are visible throughout the early period of Greek cinema and were to be resolved only after the Second World War. Because of its specific iconographic sources and the prevailing visual cultures formed by shadow theater or folk painting, Greek cinema could not embark on the production of large historical epics as in Italy by Enrico Guazzone or Giovanni Pastrone. From its very beginnings, it focused on small-scale productions whose principal objective was to supplant the existing modes and genres of popular entertainment.

The documentaries of the Maniaki Brothers do not belong to a single national cinema. They constitute the “primary foundational texts” of the whole cinematography that was to evolve with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War. The li...