eBook - ePub

America's Film Legacy, 2009-2010

A Viewer's Guide to the 50 Landmark Movies Added To The National Film Registry in 2009-10

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

America's Film Legacy, 2009-2010

A Viewer's Guide to the 50 Landmark Movies Added To The National Film Registry in 2009-10

About this book

America's Film Legacy, 2009-2010 is a guide to the most significant films ever made in the United States. Unlike opinionated "Top 100" and arbitrary "Best of" lists, these are the real thing: groundbreaking films that make up the backbone of American cinema.

Each of the 50 newest titles in the National Film Registry is covered in a detailed essay that includes cast, credits, and major awards, as well as screening information and film stills. From well-known movies like The Muppet Movie and Dog Day Afternoon, to more obscure films, like A Study in Reds and Hot Dogs for Gauguin, Daniel Eagan's beautifully written and updated edition is for anyone who loves American movies and who wants to learn more about them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access America's Film Legacy, 2009-2010 by Daniel Eagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Newark Athlete

A frame from one of the earliest extant films.

Thomas Edison, 1891. Silent, B&W, 1.33. 19mm. 1 second fragment.

Credits: Filmmakers: W.K.L. Dickson, William Heise.

Additional credits: Title supplied later. Also known as Club Swinger, no. 1; Indian club swinger; Newark Athlete (with Indian Clubs). Filmed in May or June, 1891.

Other versions: Gordon Hendricks, author of The Edison Motion Picture Myth, prepared a twelve-second copy of the film by rephotographing the original frames.

Available: Library of Congress American Memory site, memory.loc.gov

The earliest film on the Registry, Newark Athlete marked an important step in the evolution of Thomas Edison’s idea for a Kinetoscope “Moving View,” which he wrote down in October, 1888. With laboratories in Menlo Park, New Jersey, and then in West Orange, Edison developed several lines of business based on his inventions. He also cultivated a public persona as an inventor, earning sobriquets like “the Wizard of West Orange.”

By 1888, Edison, who received his first patent in 1869, had already developed a cylinder phonograph, the first practical means of recording sound. He had improved telegraph transmissions, developed the light bulb, and had opened the first electric power plant in New York City. The Kinetoscope would draw from his previous inventions and also from the work of several other innovators.

Many nineteenth-century toys operated on the principle that under proper conditions we see sequential images as a single moving image. These conditions include displaying the images at an adequate speed (usually more than ten per second) and using some form of shutter system to prevent them from blurring together. The thaumatrope, the phenakistoscope, the stroboscope, and the zoetrope are just some of the examples that had been popular since the 1830s.

Edison had met with Eadweard Muybridge and had seen the photographer’s “zoopraxiscope,” essentially a version of a phenakistoscope, but one which projected images painted onto glass disks through a lens. Edison thought he could combine the results of a zoopraxiscope with those from his phonograph, perhaps by arranging small photographs on a cylinder and then viewing them through a lens. He assigned his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, and Charles A. Brown to the project.

Dickson and Brown did not make much progress until Edison returned from a European trip during which he met French inventor Etienne-Jules Marey, who was also working on a motion picture machine. Marey placed images, or photographs, on a strip of film which was then pulled in front of a lens—more like a ticker tape machine than a phonograph. Edison hired William Heise, who had experience with similar machines, to assist Dickson. They built a horizontal-feed camera that exposed images on a 3/4–inch film strip. Small perforations helped move the film through the mechanism.

The first examples were viewed through a peephole device Edison would market as the “Kinetoscope.” Edison showed what later became known as Dickson Greeting to members of the Federation of Women’s Club on May 20, 1891. In the film, Dickson smiled and bowed. As reported in Phonogram magazine: “Every motion was perfect, without a hitch or a jerk.”

Several films were made at the time, including one of lab worker James Duncan smoking a pipe and another of various athletes from the Newark area. These were filmed in a building Dickson had commissioned in 1889 for photographic experiments.

Newark Athlete, also Club Swinger no. 1 and Indian Club Swinger, exists in two fragments. The first version shows a youth holding two clubs which he starts to swing to his left. The shot lasts for one second, or about 30 frames. A second fragment loops, or repeats, this image six more times.

In The Emergence of Cinema, film historian Charles Musser points out several important features about these experiments. First, Dickson filmed his subjects against a black background, which made them easy to see. Second, he framed them differently, sometimes using full-body shots, sometimes moving in for close-ups. As Musser put it, “Variety in camera framing and the focal plane were assumed from the outset.” Third, Dickson seemed to be drawing from Muybridge for his subject matter.

Just as it had been for Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope, photographing athletes—in this case someone exercising with clubs, later muscleman Eugen Sandow posing, and soon boxers re-enacting matches—was a natural fit for the new process. Athletes moved, which is what suited the medium best. Films of a lab worker smoking a pipe, or Dickson shaking hands with Heise, offered little that couldn’t be accomplished with still photography.

Sports in fact would drive motion pictures, make them economically viable, teach an audience to value them. The same would happen when television and then cable were introduced to consumers. Sports and athletes were big reasons why viewers purchased television sets, and why networks covered athletic events so diligently.

Edison told reporters how excited he was about the films, which he claimed solved earlier problems in taking photographs fast enough to reproduce smooth motion. “Now I’ve got it,” he said, adding, “That is, I’ve got the germ or base principle. When you get your base principle right, then it’s only a question of time and a matter of details about completing the machine.”

On August 24, 1891, Edison filed patents for his motion picture camera (the “Kinetograph”) and the Kinetoscope. It would take him several years before he could market a machine for projecting movies.

Dickson, meanwhile, set out to improve the process. One of his first steps was to switch from a horizontal feed to a vertical one. He also replaced film that was three-quarters of an inch wide with stock that was twice as wide, similar to today’s standard 35mm. He bought both negative stock for exposing and positive stock to make prints. Dickson also ordered two lenses, including a telescopic lens for shooting distant objects.

Edison planned to introduce his invention to the public at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That meant Dickson would have to come up with more product. In December, 1892, he began construction of the Black Maria, the world’s first motion picture studio. (For more information about Dickson and the Black Maria, see Dickson Experimental Sound Film, 1894.)

A Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire

License plates provided clues to dating A Trip Down Market Street. Courtesy Rick Prelinger.

Miles Brothers, 1906. Silent, B&W, 1.33. 35mm. 13 minutes.

Credits: Filmed for Miles Brothers Moving Pictures. Supervised by Earl Miles.

Additional credits: Filmed on April 14, 1906.

Available: Internet Archive, www.archive.org

The film industry in the United States first centered around New York City, with companies like Thomas Edison, Vitagraph, and American Mutoscope located in or around Manhattan. Movies spread as cameramen sought new subjects for travel pictures, as promoters went on tour with packages of films, and then as theaters opened in towns and cities. Production companies followed: William Selig opened Selig Polyscope in Chicago in 1896; Siegmund Lubin, the Lubin Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia in 1902.

In San Francisco, the Cineograph Theatre, one of the first in the country devoted exclusively to movies, opened on Market Street in 1897. The four Miles Brothers—Harry, Herbert, Joseph, Earl[e] C.—became involved in the industry soon after, first by touring with films in Alaska, then opening a storefront theater in Seattle in November, 1901. It cost a dime to watch a program, and according to film historian Charles Musser, the brothers could make as much as $160 a day. However, they had trouble securing enough titles to satisfy customers, who soon abandoned the theater for other entertainment.

The brothers tried making their own films, like Dog Baiting and Fighting and Blasting in Treadwell Gold Mine, which they sold to American Mutoscope, better known as Biograph, in New York City. They were working out of a New York office in 1903 when they hit upon a new strategy. Production companies like Edison or Biograph generally sold their titles outright to theaters. In December, 1903, Biograph began to switch its moviemaking efforts from “actualities,” which is how the industry referred to nonfiction films, to “story” films. To get rid of its backlog of actualities, Biograph sold them on the cheap at eight cents a foot.

The Miles Brothers bought up as many Biograph titles as they could, then headed for San Francisco. Along the way they offered the titles to small-town theater-owners on an exchange, or rental, basis. Renting instead of selling films quickly became the industry norm.

The brothers retained their office in New York, and marketed their own titles through the Miles Brothers Moving Pictures. They also distributed foreign films. In 1906, they decided to concentrate more on making films than distributing them, and built a large, state-of-the-art studio in San Francisco. Years later The Moving Picture World was still writing about the all-electric facility that Harry Miles designed.

According to film historian Geoffrey Bell, the Miles Brothers gained a reputation for innovative movies, like A Trip Down Mt. Tamalpais, which placed a camera on the front of a train to show Marin County views. For A Trip Down Market Street, Harry Miles equipped a camera with a special magazine that could hold a thousand feet of film, enough for roughly ten minutes. Miles had it mounted on the front of a cable car and then filmed, in one continuous take, the entire Market Street run, from 8th Street to the Ferry Building. (The film actually begins at the site of the Miles Brothers studio at 1139 Market Street.)

A Trip Down Market Street was originally made for Hale’s Tours and Scenes of the World, an amusement park novelty in which movies were shown in a small theater that was outfitted like a railroad car. George C. Hale, a former fire chief, opened the first in Kansas City in 1905, and soon licensed similar theaters throughout the country. Customers paid a dime to watch movies shot from trains, accompanied by “a slight rocking to the car as it takes the curves” and the occasional “shrill whistle” and “ringing bell,” as Hale’s promotional materials promised. Soon entrepreneurs were offering Trolley Car Tours or a simulated flight in a hot-air balloon.

For years it was assumed that A Trip Down Market Street was filmed in 1904 or 1905; the Library of Congress set the date as September or October of 1905. But David Kiehn, a film historian and archivist at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum at Fremont, California, had second thoughts. He checked the five San Francisco newspapers of the time, but could find nothing about the production. He had noticed rain puddles in the film, but weather reports for fall of 1905 spoke of “bone dry” conditions.

From the angle of the sun and construction records, Kiehn dated the film to late March or April, 1906. He confirmed from a license plate that one Jay Anway registered his car in early 1906. Kiehn discovered a Miles Brothers ad for A Trip Down Market Street in the April 28th edition of the New York Clipper, a trade magazine.

When his research was done, Kiehn had pinpointed the shooting of A Trip Down Market Street to April 14, just four days before an earthquake devastated the city. After processing the footage in their lab, the brothers sent a print by train back to their New York office on April 17.

Seen today, A Trip Down Market Street is a film of hypnotic beauty and wrenching poignancy. The camerawork is exceptional, pulling viewers in as the cable car moves forward inexorably. Details of the past emerge with startling clarity: stiff-looking clothes, boxy trucks, reckless pedestrians. Some cars seem to circle the block to pull back in front of the camera. Horses seem to outnumber automobiles. The tower of the Ferry Building, at first almost obscured by mist, looms in the frame.

In a matter of days, all would be lost. As Kiehn put it, “It is very possible that the people who are staring right at the camera, and if you look at it, right at you, those people would be gone in just a few days.”

The Miles Brothers lost their studio to fire, but still rushed to cover the disaster. A newspaper reporter wrote, “The Miles boys began taking the pictures while the houses were crumbling from the first earthquakes and did not stop until after the fire had swept over the city.” However, they had to drop their plans of making story films. Instead, they returned to actualities. They also began to film prizefights with some success. After the death of Harry Miles on January 1, 1908, the company went into a decline.

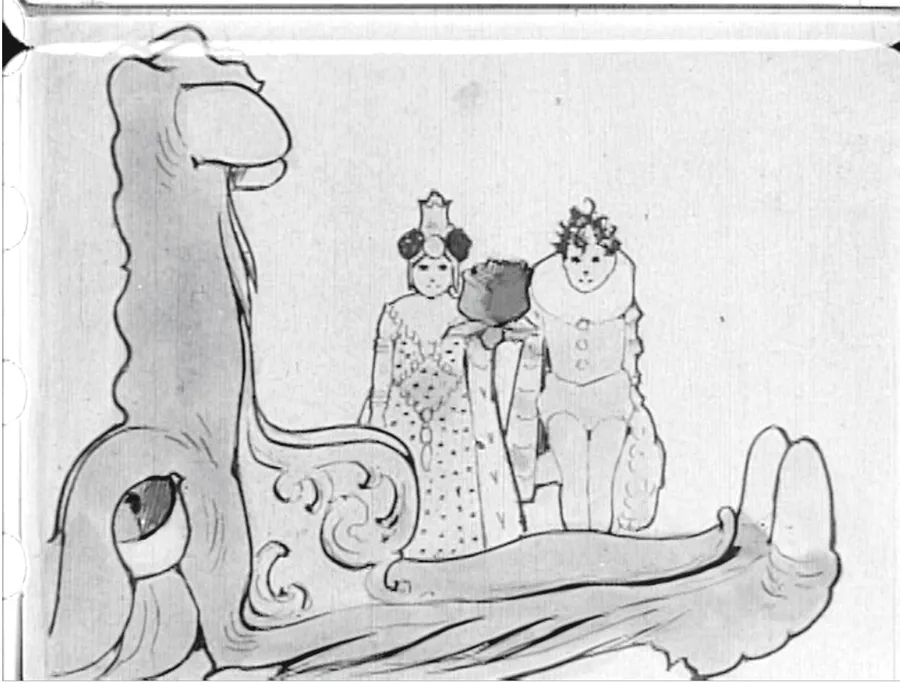

Little Nemo

The Princess and Little Nemo in Winsor McCay’s groundbreaking animation. Courtesy of Milestone Film & Video.

Vitagraph, 1911. Silent, B&W with hand-coloring, 1.33. 35mm. 11 minutes.

Credits: Supervised by J. Stuart Blackton. Animation by Winsor McCay.

Additional credits: Title on screen: Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics. Released April 8, 1911.

Available: Milestone Collection DVD Winsor McCay: The Master Edition (2003). UPC: 0–14381–1982–2–5.

Winsor McCay was not only the most advanced animator of his time, he was also a canny marketer who knew how to promote himself and his products in newspapers, vaudeville, and on film. (For more about McCay’s background, see Gertie the Dinosaur, 1914). McCay didn’t invent comic strips, but he was the first to realize their full potential, both artistically and economically. He brought the medium to a le...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction to the 2009–2010 Edition

- Introduction to the Original Edition

- Acknowledgments

- How to Read the Entries

- List of 2009–2010 Selections in Chronological Order

- List of 2009–2010 Selections in Alphabetical Order

- 2009–2010 Films

- Index of Films and Principal Filmmakers

- eCopyright