Chapter 1

Watching Scotty Grow

The New Top 40 and the Merging Spheres of Adults and Preteens

A glance at the record collection of a typical preteen in the early 1970s may well have revealed the following trio of hit singles: “Rubber Duckie” by the Sesame Street muppet Ernie, replete with splashes and squeaks, Johnny Cash’s “What Is Truth,” a thoughtful, spoken-word rumination on the Vietnam War and youth culture, and Donny Osmond’s “Sweet and Innocent,” in which the prepubescent singer warns a virtuous young girl to beware of the carnal and corrupted likes of him.1 These three records were ideal candidates for airplay on Top 40 and “middle-of-the-road” (MOR) hybrid formats during those years. Sometimes referred to by radio programmers at the time as “blended play,” the formats reflected a decided merger between the spheres of the preteen and adult, who were the primary audiences for Top 40 and MOR respectively.2 Thus arose a peculiar early ’70s radio soundscape in which gentle love songs — many of them by teen idols — aired side by side with playful sexual double entendre, topical novelty songs, and a plethora of recordings featuring adults celebrating the world of children.

The Sesame Street muppet Ernie peaked at no. 16 on Billboard’s Hot 100 with his “Rubber Duckie” single, perched alongside the Carpenters’ “(They Long to Be) Close to You” on September 26, 1970. Promo ads by Columbia Records touted the record’s release by “popular demand” from the “same people who want Dylan, Chicago and BS&T [Blood, Sweat & Tears].”3

With these interweaving characteristics, blended play formats of the early ’70s served as a locus of dialogue between the formats’ two target audiences — adults and preteens. The music emanating from those stations, furthermore, can best be understood as an active reassessment and renegotiation of identity between those same two audiences. Would the new generation of teenagers prove to be as radical — and potentially violent, as in the case of notorious fringe groups like the Weather Underground Organization— as teenagers in the ’60s? In an era when divorce rates were exploding and single parenthood was becoming increasingly common, how might children be affected in the long run by this movement away from traditional family structures? What sort of person was the modern-day parent and how permissive should this parent be? Should media have tightened or, in fact, loosened its restrictions on content for childrens’ sake? To what extent, and how early, should children have been privy to the concerns of adults both in terms of the immediate family and also on a larger-scale political level? In the wake of the turbulent, youth-oriented 1960s, Americans were asking all of these questions and more, while hit radio stations made for a particularly active on-air forum for these same issues.

The Teen and Preteen Schism

When social critic Theodor Adorno weighed in on popular “radio music” circa 1945, he dealt the sort of low blow that would inspire more than a few similarly minded critics for years to come: he called it children’s music. “We have developed a larger framework of concepts such as atomistic listening and quotation listening,” he wrote, “which lead us to the hypothesis that something like a musical children’s language is taking shape.”4 Columbia Records’ Mitch Miller echoed this sentiment somewhat in 1958 when he stood before a convention of Top 40 disc jockeys during the golden age of rock ’n’ roll radio and memorably chided them for catering to the “eight- to fourteen-year-olds, the pre-shave crowd that makes up 12% of the population and zero percent of its buying power, once you eliminate the ponytail ribbons, Popsicles and peanut brittle.”5 But this same audience, in alliance with the older teenage segment, was actively turning Top 40 into a profitable American cultural phenomenon.6 In 1957, the year before Miller’s speech, teenagers had received approximately $9 billion in allowances, and they were spending a sizeable portion of this on records.7 By the end of the decade, sales of 45 rpm records, marketed primarily to teens, raked in $200 million.8

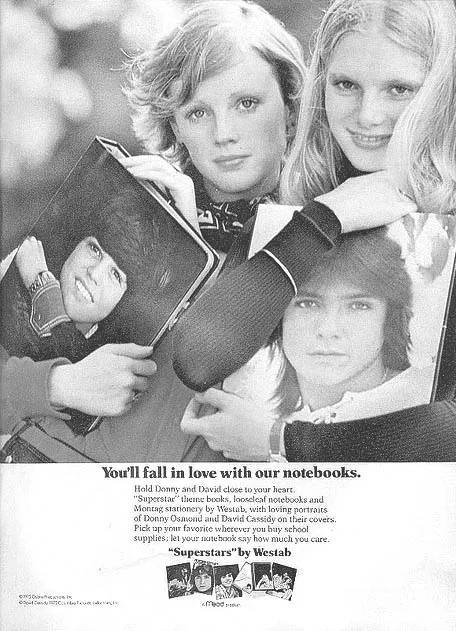

The preteen market became especially pronounced in the early ’70s with the emergence of young idols such as Donny Osmond and David Cassidy (of the Partridge Family). Both of them dominated the covers of teen magazines like Tiger Beat and 16, even while their record labels worked on “opening the door,” as Billboard wrote of Osmond’s 1972 Too Young LP, to “MOR and adult audiences.”9

By the early 1970s, though, as hit radio fragmented into formats, the future of Top 40 grew increasingly uncertain. At this juncture, the radio industry approached the preteen audience — roughly ages 6 to 13 — as a prospect entirely different from their older siblings. (“Preteen” and, especially, “tween” are more recent terms regarding a demographic often referred to simply as “children” in ’70s trade papers. My usage of the term “preteen,” thus, can be read interchangeably with the term “children.”)10 There were unavoidable reasons for this difference. Foremost among these was that a good portion of the advertising aimed toward older teenagers for products such as automobiles, auto accessories, sound systems, and beauty products was hardly likely to have had much of an immediate impact on the preteen demographic.11 Also, because preteens had less cash at their disposal, they tended to purchase 45 rpm singles as opposed to the long-playing albums favored by older teens and the new FM album-oriented radio stations they had begun listening to.12 The most significant factor in the emergence of the preteen radio audience, though, was its own enthusiastic response to the influx of new musical product that came into existence exclusively with them in mind. Top 40 sensations such as the Archies, the Partridge Family and the Osmonds demonstrated how profitable the preteen market could be even when isolated from the older teenage market.

Top 40 actually survived this new era by merging together with MOR, or the “middle-of-the-road” format. Developed for the more financially reliable adult audience, MOR filled a gap that existed between youth-oriented formats (Top 40 and progressive), and adult-oriented formats (easy listening), which usually featured vocalists like Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, and Eydie Gorme, and had the highest share of listeners over 30.13 Eschewing any harder-edged rock, soul, or country hits, regardless of chart position, MOR generated a laid-back, introspective, “soft rock” sound, typified by such performers as the Carpenters, James Taylor, and Bread. Throughout the early ’70s, however, the MOR format consistently incorporated playlists that appealed to preteen audiences, with liberal doses of bubblegum and novelty tunes added in, thus preserving what appeared to be a more democratic, all-ages-included Top 40 approach.

In truth, most radio stations lacked faith in the preteen audience as a profitable target audience on its own, so they found in MOR an even more lucrative safe haven for the still-valuable preteens.14 There were cultural implications in this development. The format provided musical proof, for one, that the borders between childhood and adulthood, as a number of cultural critics would be warning about adamantly by the end of the decade, were indeed crumbling. The education professor Neil Postman, for one, criticized a “tendency toward the merging of child and adult perspectives,” which can be “observed in their tastes in entertainment.” In America, he elaborated, radio has become merely an “adjunct of the music industry,” and as a consequence, “sustained articulate and mature speech is almost entirely absent from the airwaves.”15 In terms of radio, the situation Postman described seemed to present a contradiction: children were encouraged by hit radio to grow up too fast through frequent exposure to adult-oriented musical themes and marketing tactics, while adults were similarly encouraged to accept child-oriented music, such as “Rubber Duckie,” as a substantial part of their daily radio listening diet. Following a decade where the generation gap between parents and teenagers had grown considerably wide and ominous, such programming seemed to foster a refreshing sense of intergenerational harmony.

The “Younger Generation” in the ’60s

When Time magazine chose “the man — and woman — of 25 and under,” as its 1966 “man of the year,” the magazine saw in this figure the prognosis of an extraordinary new generation blessed with “ever-lengthening adolescence” ready to “infuse the future with a new sense of morality” and a “transcendent and contemporary ethic” that could change American society for the better. The 1950s, after all, cultivated William Whyte’s “organization man,” David Riesman’s “lonely crowd,” Paul Goodman’s “empty society,” as well as the “white collar man,” whom C. Wright Mills personified as a “small creature who is acted upon but who does not act, who works along unnoticed in somebody’s office or store, never talking loud, never talking back, never taking a stand.”16 The youth of the ’60s, on the other hand, reacted to this with marked assertiveness, and music, Time declared, was this generation’s “basic medium,” reflecting not only its “skepticism and hedonism,” but also its “lyrical view of the world.”17 Indeed, the young people Time saluted would wield a tremendous degree of cultural influence over the rest of the decade, at least.

Time magazine chose “the man — and woman — of 25 and under” as its 1966 “Man of the Year,” for whom music was its “basic medium,” reflecting not only its “skepticism and hedonism,” but also its “lyrical view of the world.”

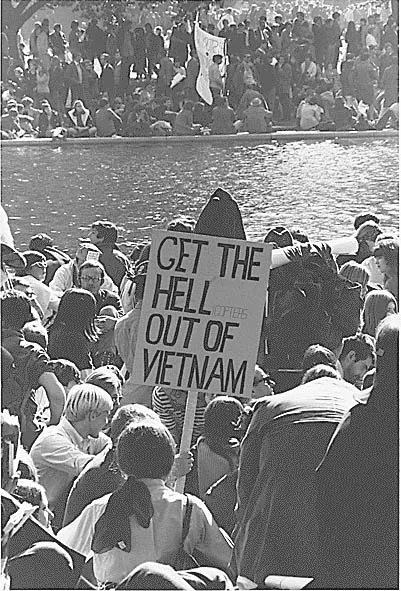

The sociological tempest of the late ’60s, then, became this generation’s legacy. By the summer of 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson committed 50,000 troops to Vietnam, student protests — with the polite title of “teach-ins” — had already become familiar American university events. As fighting intensified in Southeast Asia between the years 1966 and 1967, so too did the protests. At Cornell University, Secretary of State Dean Rusk gave a speech to a sea of faces wearing skeleton masks, and at Indiana, the boos and catcalls made it impossible for him to speak at all. Students at Howard University burned an effigy of Selective Service director Lewis Hershey, while a mob of Harvard students surrounded Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s car, forcing him to address them from his car’s hood amid a hailstorm of verbal taunts.18 Although the demonstrations during these years, including one at the Pentagon in October 1967, which drew over 100,000 activists, became more frequent and confrontational. The steady arrival of dead soldiers from overseas, as well as the specter of Selective Service, continued to haunt young Americans well into the ’70s as the fighting dragged on.19

Media coverage of student unrest in the late ’60s and early ’70s presented a seemingly steady onslaught of unsettling images depicting youth gone wild. Left to right: Columbia University in 1968; The University of Wisconsin’s Sterling Hall in 1970 (bombed by four students for housing an Army-funded research center); The Democratic National Convention in Chicago 1968.21

The war fanned the flames of a thriving youth counterculture. One of the earlier, high-profile manifestations of this was the “Human Be-In,” organized by Allen Cohen, editor of a San Francisco underground newspaper called The Oracle, and artist Michael Bowen. Held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in January 1967, the e...