![]()

Chapter 1

‘There’s more than one way to lose your heart’

The teen slasher film-type, production strategies, and film cycle

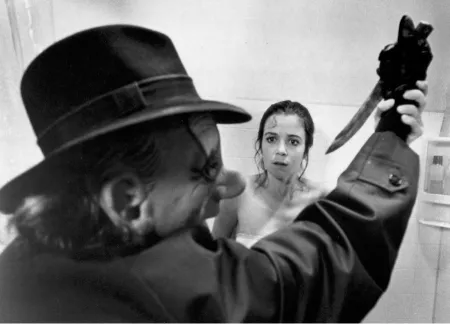

A teenage girl showers, unaware of the masked intruder creeping down her hallway. The prowler slips into the bathroom and rips aside the shower curtain. The youth turns, screaming as the madman projects his blade towards her midriff. She grabs her assailant’s wrist and struggles valiantly, but the weapon inches mercilessly towards her flesh. Inevitably, the maniac’s weapon reaches the girl’s skin. But the blade bends pathetically on impact — it is rubber. Confused, but unhurt, the plucky teenager unmasks her attacker to reveal a grinning boy. ‘Joey!’ she yells. Her kid brother laughs and flees (see Figure 1.1).

So begins The Funhouse (1981), not a teen slasher, but leading horror director Tobe Hooper’s playful tribute to fifty years of American horror. Made for Universal Pictures in late 1980, when teen slasher film production and distribution had been gaining momentum, The Funhouse misleads audiences into anticipating a film modeled on the most high-profile teen slasher of the time, Halloween (1978). ‘The parody of Halloween’, remarked Bruce F. Kawin, ‘is entirely explicit’ (1987, p. 105).

The opening of The Funhouse captured the essence of the teen slasher’s distinct content, the commercial logic that underwrote its production in the mid-to-late 1970s and early 1980s, and its status as a nascent film-type. Encapsulated in the scene is the combination of everyday locations, fun-seeking young people, and shadowy knife-killers that set teen slashers apart from other films. Similarly, by inviting parallels to a hit like Halloween, promising but not delivering brutal violence, and showcasing light-hearted material oriented to youths of both sexes, the prologue to The Funhouse reflected the strategies implemented by teen slasher producers to make their product economically viable. Finally, by inviting, but refusing to allow, audiences to anticipate a film like Halloween, Hooper and his collaborators position The Funhouse in relation not only to Halloween but to similar films that were hitting American theaters at the time, and, in doing so, evoke the on-going process that was making teen slashers part of American film culture. The opening scene of The Funhouse gestured in light-hearted fashion to the American film industry’s understanding of teen slasher film production, which is the focus of this chapter.

FIGURE 1.1 Evoking the teen slasher film in The Funhouse.

This chapter provides three conceptual frameworks that structure the industrial analysis presented across subsequent chapters, outlining the textual model employed by teen slasher filmmakers, identifying the strategies they implemented to help to realize their commercial objectives, and proposing a model of film cycle development which illuminates the ways in which filmmakers conduct was impacted by developments specific to the point in time at which they contributed a film to the cycle. By abandoning the assumption that early teen slashers were made solely to horrify male drive-in patrons, irrespective of when they were produced, this chapter permits the book to approach the films as multifaceted products that were fashioned to permit astute businesspeople to realize relatively lofty ambitions. In doing so, it suggests that, only by treating film-types as complex networks of elements designed to provoke diverse types of audience engagement and to fulfill different commercial objectives, can the conditions underwriting production and the mobilization of content be identified.

‘An easy-to-follow blueprint’: the Teen Slasher Film-Type

At its core, film genre is a system of communication comprising two components, the label and the corpus. A name is assigned to a number of films because they are considered to share similarities that distinguish them from other films, thus bringing order to relative chaos. However, as Steve Neale (1993), James Naremore (1998), and Rick Altman (1999) have shown, that order is somewhat illusionary because the relationships between the label and the corpus rarely are stable. The application of the label and the choices of films are impacted by countless factors including ‘personal taste’, knowledge of, and investment in, the films, as well as by geographic and temporal conditions. For example, Mark Jancovich (2000) revealed that horror fans possess distinct conceptions of the texts that constitute the horror film, while Neale (1993) demonstrates that melodrama originally referred to male-oriented action films, not emotionally wrought female-audience films. The contestation and flux characterizing genre has led some scholars to adopt one of two approaches. Approaching genre as a primarily discursive activity, scholars including Naremore (1998) and Jancovich (2000) have examined the roles played by genre in film reception such as journalism and fan commentary. The second approach, advocated by Neale (1990), and employed by, among others, Thomas Doherty (2002), Tico Romao (2003), and Kevin Heffernan (2004), maintains that, through rigorous empirical research, film historians can reveal the temporal specificity of film categories so as to gain insight into production, promotion, distribution, and exhibition practices.

Yannis Tzioumakis’ work on ‘American independent cinema’ (2006) has shown that the two approaches are not always incompatible. For Tzioumakis, ‘independence’, in the American context, is both a discursive activity that distinguishes films from an imagined ‘mainstream’, and an institutional category denoting films that are not handled by major studios (ibid., pp. 1–14). Tzioumakis shows that a strong correlation exists between discursively and institutionally ‘independent’ American films. While there may be some debate as to whether ‘American independent cinema’ constitutes a genre, it certainly provides a way of categorizing and distinguishing films in much the same way as universally accepted genres like the Western or the horror film. Much like ‘American independent cinema’, the films of the mid-to-late 1970s and early 1980s that came to be known as teen slasher films offer a prime example of discursive activity and industrial conduct exhibiting a high degree of regularity — albeit for a brief time.

Even though, as we shall see below, no stable labeling system had become established by 1980 and 1981 to describe what I and many other scholars now call teen slasher films, it is clear that, at this point in time, individuals speaking from all levels of North American film culture, from producers, distributors, and exhibitors to industry analysts, reviewers, casual moviegoers, and fans, recognized the existence of a new type of film that was distinguished from other films by virtue of the story it told — the story of a blade-wielding killer preying on a group of young people. In this respect, the teen slasher fulfilled three of the four criteria laid out by Altman (1999) as constituting what he calls a genre or what I call a film-type. Its distinct story exemplifies what Altman termed the ‘structure’ i.e. shared content (ibid., pp. 14–15). That story provided a ‘blueprint’, the general model used by filmmakers to fashion new examples of the film-type (ibid.). And, the fact that audiences recognized the film-type’s distinct story demonstrates that existing between teen slasher film producers and consumers was what Altman described as the ‘contract’ (ibid.), a state reached when viewers hold firm expectations of the ‘structure’ that will be delivered by films made to the ‘blueprint’. Missing is what Altman dubbed the ‘label’, a name that conveys relatively unambiguously the alignment of ‘structure’, ‘blueprint,’ and ‘contract’ in such a way as to demonstrate that speaker/writer and listener/reader recognize that a film features a ‘structure’ because it has been fashioned to a ‘blueprint’ thus establishing a ‘contract’. Instead, numerous etiquettes circulated contemporaneous to the early teen slasher films. Many were hyphenated labels comprised of different combinations of terms that communicated the film-type’s distinct story, others, as is elucidated in the next section, were descriptive phrases that emphasized the links between examples of the film-type. The fact that none of these etiquettes have been widely adopted and that those etiquettes which did gain currency at a later date — teenie kill-pics (Wood 1983, 1987), stalker films (Dika, 1990; Rubin 1999), slasher movies (Clover 1992), and teen slasher films (Wee, 2005, 2006) — were not used when the films were produced and first released, indicates that a more reliable gauge of whether or not several films are perceived to represent a coherent group (or genre or film-type) is provided by efforts to communicate that sense of belonging rather than by the existence of a single label.

Because of ambiguities concerning the manner in which films about young people being menaced by blade-wielding killers subsequently have been labeled by scholars, concerning the films to which scholars have applied the label ‘slasher’, and concerning the complex interplay between the two phenomena, it is essential to provide a definition of the films to which this study applies the term ‘teen slasher film’. Although many scholars recognize that the term ‘slasher’ is commonly applied to films about young people being menaced by blade-wielding killers and that films featuring this content commonly are labeled ‘slasher films’, ‘slasher’ has also been used as a synonym for so-called splatter films (filmic showcases for gore), in reference to films which feature blade-wielding killers irrespective of their targets’ ages, and to youth-centered horror films irrespective of the monster presented therein, while films about blade-wielding killers preying on young people have, as noted above, been given numerous labels in academic writing. More so than any other factor, however, confusion has been caused by the fact that many of the writers that outlined as their locus of interest tales of blade-wielding killers preying on young people and that presented detailed descriptions of the films’ distinguishing content, actually jettisoned their definitions when illustrating their arguments. This tendency, and its consequences, are nowhere clearer than in the case of the much-cited article, and later book chapter, ‘Her Body, Himself’, in which Carol J. Clover forwarded the concept of cross-gender identification, not with reference to the youth-centered ‘slasher films’ she described across the majority of the piece, but mainly with adult-centered thrillers like Psycho (1960), Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), and Dressed to Kill (1980) (1992, pp. 46–50). Such slippages, whether calculated or otherwise, are not without their implications. Clover’s assimilation of the two distinct film-types that Robin Wood (1983), four years earlier, had called the ‘teenie kill-pic’ and the ‘violence against women film’, so as to form a critical category that, I maintain, did not exist on celluloid in the years before her piece was published, influenced scholarly and popular perceptions of the teen slasher profoundly. Appearing in what was widely received as groundbreaking film scholarship, Clover’s definition provided an immediate reference point for academic and popular writers (Whitehead, 2000, pp. 7–16; Rockoff, 2002, pp. 5–22; Armstrong, 2003, pp. 1–19; Harper, 2004, pp. 31–61), who, by restating its key tenets, proliferated, gave credence to, and reinforced misconceptions of teen slasher content, particularly the erroneous, but remarkably enduring, claim that the films showcased psychosexually disturbed male sadists torturing and murdering scores of beautiful, independent young women (see for example Prince, 2000, pp. 298–306, 351–353; Wee, 2005; 2006).

Amidst such confusion and misunderstandings, I aim to represent the textual model that distinguished, and was recognized contemporaneously as distinguishing, from other films, the content of the teen slashers of 1974–1981: a story-structure that could be articulated differently and combined with content drawn from a variety of sources and which enabled filmmakers not only to provoke audience horror, but also to incite intrigue, thrills, and amusement. While expressed in terms used by structuralist scholars, I am not suggesting that the story-structure imposed a mode of engagement on individual viewers, as structuralists have done. Rather, the story-structure is designed to distinguish what I call teen slasher films from other tangentially similar films in such a way as to reflect, in as organized and articulate a way as possible, the manner in which the films were perceived upon their original releases, based on the recorded testimony of industry-insiders, industry-watchers, and audiences.1

By late 1980, the film-type that came to be known as the teen slasher film was recognized widely across the North American film industry, in the trade and popular press, and by theatergoers soon thereafter, as industry-professionals, industry-watchers, and young people spoke openly and articulately about the content that distinguished it as a new type of film. Producers and distributors, even those who had never even made a teen slasher, spotlighted its distinct features. ‘It’s all a game’, explained horror filmmaker Christopher Pearce, ‘a group of coeds are endangered. Who is it? What is it?’ (quoted in C. Williams, 1980, p. E1). A similar point was made by a top US distribution executive. ‘If you get the audience to identify with young teens in trouble and you do a knife movie’, suggested Avco Embassy’s Don Borchers, ‘it’s always going to work’ (quoted in Knoedelseder, 1980a, p. N3).

Films about young people being menaced by shadowy maniacs, far from having been ‘never even written up’ by American journalists, as Morris Dickstein suggested (1984, p. 74), had in fact initiated a light-hearted competition to coin an appropriately descriptive and catchy generic label among writers at the most widely read newspapers in North America. Alongside terms like ‘horror’, ‘thriller’, and ‘mystery’, which Jancovich (2009) shows have often been used interchangeably by reviewers to describe films now commonly thought of as ‘horror movies’, countless sobriquets spotlighted the combination of young people and blade-wielding killers that industry personnel noted as distinguishing the film-type.2 Ed Blank wrote in the Pittsburgh Press of ‘slash-your-local teenager features’ (1981, p. 6), the Los Angeles Times’ Linda Gross discussed the ‘young-folk-getting-killed-genre’ (1981b, p. H7), and, at the New York Times, Aljean Harmetz examined the ‘homicidal-maniac-pursues-attractive-teen-agers’ sweepstakes (1980d, p. C13). But Washington Post employees were the most gleeful participants, with Tom Shales commenting on ‘endangered teen-ager movies’ (1981, p. C2), Joseph McLellan speaking of ‘the ‘kill-the-teenagers’ cycle’ (quoted in Arnold et al., 1980, p. F1), and Judith Martin taking aim at ‘the teen-age Blood Film’ (1981, p W19). Not to be outdone by these epithets, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune described Happy Birthday to Me (1981) as a ‘typical “teen-age girl takes violent revenge on kids who have been mean to her” flick’ (1981b, p. B10). By November 1981, a Variety reviewer seemingly felt that it was high time to discontinue this labeling one-upmanship. A plot synopsis that highlighted ‘the mysterious murderer’ and ‘grad[uate students]’, s/he concluded, communicated sufficiently that The Prowler (1981) belonged to ‘the seemingly endless procession of chillers’ that comprised ‘the now familiar subgenre’ (Klad., 1981, p. 22).

Interviews conducted in summer 1981 and published in the Los Angeles Times demonstrate that that ‘now familiar subgenre’ had also been recognized by America’s theatergoing youths, adding weight to Jay Scott’s observation in Toronto’s Globe and Mail the previous fall that ‘[t]he premise — a crazed killer abused years before returns to wreak vengeance on the young — is so familiar that the audience can predict (…) every shock’ (1980b). Whereas a group of teenagers that attended urban high schools in the Venice area expressed their views on ‘Happy Birthday to Me, Prom Night, Friday the 13th and stuff like that’ (quoted in Caulfield and Garner, 1981, p. L22), graduates from an elite academy in the wealthy suburb of Irving discussed movies in which a ‘killer goes crazy and kills 15 people’, and having viewed ‘Happy Birthday to Me (…) and films like that’ (quoted in Garner, 1981, p. L29).

Recognition of the teen slasher across North American film culture was often accompanied by cogent descriptions of the narrative model that distinguished the new film-type. ‘It’s a new type of horror film’, wrote Canadian journalist Richard Labonté in respect to what he dubbed a ‘litany of recent films, each with essentially the same plot’ (1980b, p. 202). Later Labonté was even more specific: ‘It’s a genre which, like any other trend, is rooted in a formula and has a portable plot, in this case, the common denominator was the knife (hatchet, cleaver, pointed stick)-wielding psychopath stalking darkened suburban streets in search of teenage prey’ (1980c, p. 27). Labonté’s colleague at the Ottawa Citizen, Hugh Westrop, was equally direct, announcing in his review of Terror Train (1980) that the ‘plot device of a psychopathic killer stalking the nubile young is back, this time involving a crowd of college kids partying on a train’ (1980, p. 203). South of the border, Los Angeles Times film industry analyst William K. Knoedelseder Jr. considered the impact of that ‘plot device’ on filmmakers. ‘The formula provides an easy-to-follow blueprint, he outlined, ‘[g]iven some teens in trouble, all you need is someone or something to stalk them [and] a weapon for doing them away’ (1980a, p. N3). Yet, perhaps the most detailed and precise summary of the new film-type’s content came in April 1981, when the first teen slasher cycle had yet to enter its most intensive phase of releases, from Tom Sowa of the Spokesman-Review:

In films like (…) “My Bloody Valentine,” “Prom Night,” “Silent Scream”, “Friday the 13th,” and “Terror Train,”, the basic pattern always holds. Young, sometimes innocent teens get together to party or just share a little free spirit. Along comes the bogey man, and in his/her hands th...