![]()

Chapter 1

Godchild

Naked and restless in bed, Faye Dunaway finally stumbles to her second-story window to eye Warren Beatty, the contours of her back glistening with sweat. Another sweltering shot: a bird’s-eye view of Paul Newman as the wily Cool Hand Luke, having consumed an unreasonable number of hard-boiled eggs, lying stretched atop a prison mess hall table like Christ on the cross. And then there’s Jane Fonda, carrying Michael Sarrazin on her back—as well as the weight of the Great Depression and the metaphorical load of Vietnam—enduring a grueling 1930s dance marathon in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Meanwhile, in Point Blank, Lee Marvin strides down a cavernous hallway with obdurate authority, each step hammering the floor like a nail through sheet metal, intent on revenge. These nonconformists summon the pulsating spirit of American film in the late 1960s. To movie lovers, they are instantly placeable.

Less recognizable but equally significant, American film critics shaped and embroidered the 60s cinematic landscape. Composing in longhand and hovering over her writer’s easel, Pauline Kael describes Jane Fonda in Barbarella: “Her American-good-girl innocence makes her a marvellously apt heroine for pornographic comedy… According to [director Roger] Vadim, in ‘Barbarella’ she is supposed to be a kind of sexual Alice in Wonderland of the future, but she’s more like a saucy Dorothy in an Oz gone bad.” In a few paragraphs, Kael legitimates Fonda’s work in a manner that even Fonda struggled to defend, suggesting the range of her blossoming talents. From these sensibilities, John Simon recoiled. It was never enough for him to ferret out moments of art or inspiration in the mundane. He demanded more from movies and critics. “Nothing succeeds better than highbrow endorsement of lowbrow tastes,” he once wrote about Susan Sontag. “Who would not, at no extra cost, prefer to be a justified sinner?” (italics his). Now imagine a shot of the critic Rex Reed devouring a banana, along with peanut butter, jelly, and whipped cream, from the fingertips of the ingenue Farrah Fawcett (then a minor beauty, not yet one of the Majors). Of course it’s a fantasy sequence. In Myra Breckinridge Reed is Myron Breckinridge. A sex change remakes him as Myra (Raquel Welch), and, together, the alter egos pursue movie stardom. Oddly, the analogy works, as Reed used his critic-cum-celebrity persona to cross over, however briefly, into movies, however awful. Meanwhile Roger Ebert was chasing his own romanticized vision of sweetness and sin: that of the consummate newspaper critic. Routinely, he would screen a film in the afternoon, effortlessly meet the evening deadline, then interview filmmakers at a favorite pub—a punishing bar crawl that would yield only to daylight. He was equally enticed by Hollywood, having penned the script for Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. The circle was complete: Like images on the big screen, the critics, too, were stars.

Figure 2 Time for a smoke: The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, a few months after writing her review of Bonnie and Clyde. Martha Holmes/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Figure 3 A sharp tongue and collar: Film critic John Simon in 1975, at the offices of New York Magazine in New York. Michael Tighe/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The vitality in American movies of the 60s was amplified by the influence and imagination of this new generation of critics. Fresh attitudes toward films were espoused with impassioned idealism, and the nation’s bully pulpit was New York City. They made a colorful cast. Andrew Sarris began writing about film in 1955, mostly in obscure publications, and his first review for The Village Voice was of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho in 1960. Everything about that film—its content, style, and production—signaled startling changes in American movies. And Sarris loved it, parting ways with the critical vanguard. By 1968, he published The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968, daring to organize and rank the accomplishments of filmmakers. Having interned at the Cinémathèque Française and translated an English version of Cahiers du Cinéma, Sarris was drawn to French auteurism, privileging the role of the director in shaping a film’s expressive qualities. If Sarris was the courtier, Pauline Kael was the immigrant, whose piecemeal critical approach resisted frameworks. After managing and writing production notes for a theater in San Francisco and working in nonprofit radio, Kael developed her critical voice while freelancing for publications like Sight & Sound. In 1965, she reached larger audiences with I Lost It at the Movies, the first time that film criticism hit the best-seller list. That volume also reissued a critical appraisal of Sarris’ auteurist point of view. Her spirited panning, coupled with a strike at The New York Times that increased readership of the Voice, brought Sarris to the critical fore. Kael soon uprooted to New York, briefly writing for McCall’s, then for the New Republic, before settling into The New Yorker, where she remained for three decades. Ironically, while Sarris’ baroque, gentlemanlike prose appeared in the edgy Voice, Kael’s earthy, loopy style shook up the staid New Yorker. And all the while writing for The New Leader, the scrupulous John Simon maintained a vigilant eye, patrolling and protecting cultural and moral high ground from the antics of Sarris and Kael.

It was a changing of the guard. For decades, Bosley Crowther had reviewed films for The New York Times, yet by the 1960s his point of view had grown stodgy and stale. Although Kael and Sarris achieved notoriety through their aesthetic sparring, they were unified in their desire to establish a sturdy base of influence for critics. In 1966 and partly in opposition to Crowther and the conservative aesthetics of the New York Film Critics Circle, Kael and Sarris were two of twelve founding members of the National Society of Film Critics. Membership in the Circle was limited to newspaper writers. Redressing power imbalances, the National Society welcomed magazine writers as well.

Nowhere was the new epoch more evident than in stormy debates over Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. In every sense, this 1967 film packed a wallop. For some, it was a hair-raising, invigorating two hours; for others, a moral and aesthetic slap in the face. It’s hard to tell which part of the film carried the most impact: its treatment of crime and sexuality, its violent dénouement, its visual distinction recalling the French New Wave, or its announcement of dynamic new talent. Even its influence on international fashion was unmistakable. As a cultural landmark, it had a gift for provoking debates among audiences and critics. Crowther despised it. He soon retired, passing the baton to Renata Adler, whose inimitable voice and unerring judgment revitalized criticism at the Times. Commencing a lasting partnership with The New Yorker, Kael was ecstatic, her analysis alive to new sensibilities in American movies, her opening line throwing down the gauntlet to her critics: “How do you make a good movie in this country without being jumped on?” And inevitably, Simon was appalled—not only at the movie, but also at Kael’s avidity. Still, a polemic response to Bonnie and Clyde was unnecessary for membership in the new establishment. In Life, Richard Schickel was conflicted, inviting “all men of goodwill to join me here on the nice, soft grass of the middle ground.”

But most declined the invitation. There simply wasn’t much middle ground to be had. In the meantime, a young critic in the Midwest was electrified by Bonnie and Clyde, his ardor and geographic location signaling new directions for American movies. While Sarris and Kael made names for themselves in the early 60s, Roger Ebert was serving as editor-in-chief of The Daily Illini, the University of Illinois’ student newspaper. He briefly attended graduate school at the University of Capetown and the University of Chicago, but academia would be the road not taken. Ebert eventually joined The Chicago Sun-Times as its film critic in April 1967, and, to this day, he says he was offered the position because he had long hair and had written a piece on underground films. One of the first movies he reviewed was Bonnie and Clyde, which he recognized as a cultural milestone. At twenty-five and one of the youngest film critics writing for a daily, Ebert was the embodiment of a new film generation—a generation raised on Saturday matinees and older movies on the Late Show. They carried their love of movies to college, forming film societies on university campuses, where cinema studies was a burgeoning academic field. And they relished the shifts in American movies that followed the demise of the studio system and the Production Code, permitting a broader array of content on the screen. Many were literate in foreign cinema and receptive to the gradual European influence on American film. Weathering the cultural shifts that defined the late 50s and 1960s, they romanticized movies and were unembarrassed to use grandiose language. Richard Schickel: “The Wild Bunch is the first masterpiece in the new tradition of what should probably be called the ‘dirty western.’” Andrew Sarris: “Claude Chabrol’s La Femme Infidèle is the most brilliantly expressive exercise in visual style I have seen on the screen all year.” Pauline Kael: “Remember when the movie ads used to say, ‘It will knock you out of your seat’? Well, Z damn near does.” Brace yourself: imposing pronouncements were their lingua franca.

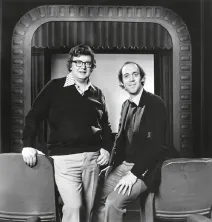

Ebert, the newest critic in Chicago, attended screenings at the Town Underground, a burlesque theater that briefly doubled as an art house under the direction of friend and cinephile John West. At the Clark Theater run by Bruce Tinz, he also devoured the classics of Welles, Hitchcock, von Sternberg, Minnelli, and Hawks. Ebert’s take on American movies left an immediate impression: readers were captivated by his direct approach, his thoughtful point of view, and—depending on the film—his sense of humor, ranging from the subtle to gregarious. So much so that in 1975 he was the first film critic to receive a Pulitzer Prize for criticism. Given his talent and beat, it seemed natural that Ebert should walk away with the laurel that the muckraker Jack Anderson coined “the Academy Awards of Journalism.” By any measure it was an auspicious year. Teaming with fellow film critic Gene Siskel of The Chicago Tribune, Ebert hosted a PBS television special, Opening Soon at a Theater Near You. They would soon share the balcony of PBS’s Sneak Previews for a national audience. Though the nomenclatures changed—moving into syndication with Tribune Broadcasting they were At the Movies, then it was Siskel and Ebert and the Movies with Disney’s Buena Vista Television, and finally Siskel and Ebert—their tart chemistry proved irresistible. For a time, their program was one of the most widely watched syndicated shows in America, second only to Entertainment Tonight, reaching an estimated eight million homes.

Figure 4 Making history: In 1975, the Chicago Sun-Times’ Roger Ebert is the first to win a Pulitzer for film criticism. Bettmann/Corbis

Ebert’s velocity as a writer is daunting, but his television presence made him the most influential critic in the country. He initially balked at the thought of hosting a program with a rival, only fearing that someone else might land the opportunity. That instinct served him well, as Siskel and Ebert’s competitiveness was central to their popularity. Their arguments were eye-popping—at least as entertaining as many films they discussed—and the show’s appeal was rooted in the authenticity of their battles. Their arguments were never staged. They didn’t socialize apart from professional responsibilities, and their relationship was stamped by begrudging affection, and at times, genuine dislike. In the wake of their success, similar programs multiplied, but Siskel and Ebert’s intellectual dexterity, lively chemistry, and unalloyed abilities to connect with audiences were unmatched.

Like seismic waves, Ebert and Siskel shifted the geography of power in the film industry. Historically, the axis had tilted between Los Angeles, where movies are made, and New York, where financial capital is consolidated. From James Agee in the 40s, to the inveterate influence of the Times, to Kael and Sarris in the 60s and 70s, New York writers had a hammerlock on critical influence. In the 1980s, however, Siskel and Ebert were the most recognized and trusted critics in the nation, bringing Chicago into the limelight. Each jockeyed for interviews with actors and directors. In kind, filmmakers wanted their ears. Even reclusive artists like Woody Allen sought out time with Ebert.

Two literate men discussing a range of topics, at once engaged and engaging—one slender and canny, the other cherubic and incisive. Sounds like another episode of Siskel and Ebert, but in this case it’s Louis Malle’s My Dinner With André, a cornerstone of American independent film. The movie is 89 minutes of two natural storytellers enjoying each other’s company over a meal. Though the film was embraced at Telluride and the New York Film Festival, its release on October 11, 1981, at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema failed to attract much of an audience. After several lackluster weeks, the film seemed destined to fade away; it was, after all, a busy holiday season at the movies. Buoyed by a phalanx of stars, a massive budget, a movie star’s directorial debut, and months of publicity, Warren Beatty’s Reds, the long-awaited love story of Communists John Reed and Louise Bryant, debuted the first week of December. On their program, Siskel and Ebert recommended Reds, but their highest praise was reserved for My Dinner. Most agree their support placed this struggling film on the map, leading to wider distribution and exhibition. Paramount’s $32 million investment in Reds never paid off, but My Dinner’s good fortune symbolized Ebert and Siskel’s fiscal muscle. They could bring an unusual, perceptive film to the public eye and generate the necessary word of mouth to get people into theaters. The movie took care of the rest.

Physically and temperamentally, Gene Siskel was a skillful reporter, a nimble thinker, and a vibrant foil for Ebert. His approach was more sober, more skeptical, more pragmatic—“realism” mattered to him. Often saying he covered “the national dream beat,” he wanted movies to reflect a country’s hopes and fears. Ebert was too quick to cheer, he argued; in turn, Ebert believed Siskel was too pessimistic. Even their bodies—Siskel’s tall, slim stature and balding head; Ebert’s short, portly physique and mop of gray hair—were Don Quixote to Sancho Panza, Laurel to Hardy, Bert to Ernie. When disagreeing, their gestures were ritualized, Ebert throwing his hands outward and upward in exasperation, Siskel aiming his index finger at Ebert. At times, their theatrics overshadowed their criticism. “Is this the night Rog will finally bite the finger Gene is forever pushing in his face?” asked colleague Richard T. Jameson. And “when will Gene call Rog on his tactic of shooting sidelong, what-am-I-to-do-with-this-nudnik? glances at the camera?”

Figure 5 Rough around the edges: Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel in the balcony of Sneak Previews (PBS), circa 1979. Photofest

Figure 6 Seasoned pros: Gene, Roger, and their iconic thumbs. The program is now Siskel & Ebert (Buena Vista Television), circa 1989. Photofest

Siskel’s route to the movies had been the more circuitous. After studying philosophy at Yale, he served as a military reporter, began writing about real estate in the Tribune, and eventually landed the job as its head film critic, thus vying with Ebert’s popularity at the Sun-Times. Although a quick-witted adversary, Siskel was never in the same league as Ebert. He loved words, and his bemused verbosity could be endearing, but there was always a restrained, perfunctory quality to his criticism. His grasp of film history was limited, confining the range and depth of his observations. He attended few film festivals, and he wrote less than his contemporaries. Reacting to the success of their television program, the Tribune sidelined Siskel in the 80s, cryptically describing him as “overextended.” Thereafter, he was relegated to writing capsule reviews for the paper—hardly an opportunity for growth. Siskel was an adroit, adaptable reporter, someone who might be as comfortable writing from the Washington bureau as evaluating a movie. For him, film criticism was a job. But for Ebert, it was a calling.

Following ten months of health difficulties, Siskel passed away on February 20, 1999. It was the end of an era. That same year, Ebert dedicated his first Overlooked Film Festival to Gene Siskel, who li...