![]()

PART ONE

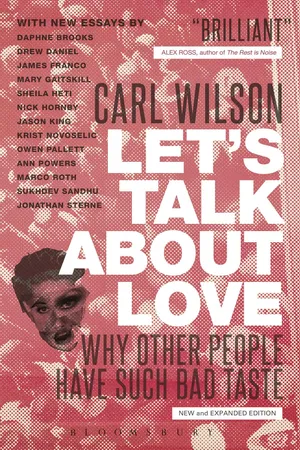

LET’S TALK ABOUT LOVE: A JOURNEY TO THE END OF TASTE

Carl Wilson

![]()

1

Let’s Talk About Hate

“Hell is other people’s music,” wrote the cult musician Momus in a 2006 column for Wired magazine. He was talking about the intrusive soundtracks that blare in malls and restaurants, but his rewrite of Jean-Paul Sartre conveys a familiar truth: When you hate a song, the reaction tends to come in spasms. Hearing it can be like having a cockroach crawl up your sleeve: you can’t flick it away fast enough. But why? And why, in fact, do each of us hate some songs, or the entire output of some musicians, that millions upon millions of other people adore?

In the case of me and Céline Dion, it was Madonna’s smirk at the 1998 Oscars that sealed it. That night in March, the galleries of Los Angeles’s Shrine Auditorium were the colosseum for the latest gladiatorial contest in which art’s frail emissaries would get flattened by the thundering chariots of mass culture. And Empress Madonna would laugh.

Until that evening, I’d done as well as anyone could to keep from colliding with Titanic, the all-media juggernaut that had been cutting full-steam through theaters, celebrity rags and radio playlists since Christmas. I hadn’t seen the movie and didn’t own a TV, but the magazines and websites I read reinforced my sureness that the blockbuster was a pandering fabrication, an action chick-flick, perfectly focus-grouped to be foisted on the dating public.

Now, I realize this attitude, and several to follow, probably makes me sound like a total asshole if, like millions of people, you happen to be a fan of Titanic or of the woman who sang its theme. You may be right. Much of this book is about reasonable people carting around cultural assumptions that make them assholes to millions of strangers. But bear with me. At the time, I thought I had plenty of backup.

For instance, Suck.com, that late 90s fount of whip-smart online snark, called Titanic a “14-hour-long piece of cinematic vaudeville” that “had the most important thing a movie can have: a clear plot that teaches us important new stuff like if you’re incredibly good-looking you’ll fall in love.” It was contrasted with Harmony Korine’s Gummo, a film about malformed but somehow radiant teenagers drifting around rural, tornado-devastated Xenia, Ohio – as if, after the twister, Dorothy’s Kansas had been transformed into its own eschatological Oz. Suck said that Gummo evoked “the vertigo we encounter when people discover and make up new standards of cool and beauty,” a sensation resisted by mass society because those standards could be “the wrong ones, and we can’t allow ourselves to look at that too hard or long.”

CNN.com’s review, on the other hand, described Gummo as “the cinematic equivalent of Korine making fart noises, folding his eyelids inside-out, and eating boogers,” and the director as a punk-ass straining in vain to be a punk. For cred, the writer namechecked the Sex Pistols, saying that unlike theirs, Korine’s rebellion came down to making fun of the hicks.

I knew which argument I bought, and it wasn’t just because the same CNN reviewer called Titanic “one swell ride.” After all, Korine was a lyrical enfant terrible who’d gotten fan letters from Werner Herzog; Titanic director James Cameron made Arnold Schwarzenegger flicks. Korine was New York and Cameron was Hollywood. And just consider their soundtracks: Gummo had a soundscape of doom-metal bands, with an alleviating dash of gospel and Bach. Titanic had Celtic pennywhistles, saccharine strings and … Céline Dion.

Living in Montreal, Quebec, made it impossible to elude Titanic’s musical attack as neatly as the celluloid one. Dion had been intimate with the whole province for years, as first a child star, then a diva of all French-speaking nations and finally an English–French crossover smash. Her rendition of James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” had come out first on her bestselling 1997 album Let’s Talk About Love, then on the bestselling movie soundtrack and then again on a bestselling single. (Ten years later, by some measures, it’s the fourteenth-most-successful pop song the world has ever seen.) I hadn’t listened regularly to pop radio since I was eleven, and I got agoraphobic in malls, but that tin-flute intro would tootle at me from wall speakers in cafés, falafel joints and corner stores, and in taxis when I could afford them. Dodging “My Heart Will Go On” in 1997–98 would have required a Unabomber-like retreat from audible civilization.

What’s more, I was a music critic. I hadn’t been one long: I’d done arts writing at a student paper, veered into leftish political journalism and then become the arts editor at one of Montreal’s downtown “alternative weeklies.” I wrote profiles and CD reviews on the side for the rakish punk-rock guitarist who edited the music section (when he dragged himself into the office in the mid-afternoon). I championed experimentalists and the kinds of unpopular-song writers I was prone to calling “literate.” I would not have deigned to listen to an entire Céline Dion album, but it was a basic cultural competency in Montreal to know her hits well enough to mock them with precision. In Quebec, Dion was a cultural fact you could bear with grudging amusement – a horror show, but our horror show – until Titanic overturned all proportion and Dion’s ululating tonsils dilated to swallow the world.

* * *

With “My Heart Will Go On,” Céline-bashing became not just a Canadian hobby but a nearly universal pastime. Then-Village Voice music editor Robert Christgau described her popularity as a trial to be endured. Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone called her voice “just furniture polish.” As late as 2005, her megahit would be ranked the No. 3 “Most Annoying Song Ever” in Maxim magazine: “The second most tragic event ever to result from that fabled ocean liner continues to torment humanity years later, as Canada’s cruelest shows off a voice as loud as a sonic boom, though not nearly so pretty.” A 2006 BBC TV special went two better and named “My Heart Will Go On” the No. 1 most irritating song, and in 2007 England’s Q magazine elected Dion one of the three worst pop singers of all time, accusing her of “grinding out every note as if bearing some kind of grudge against the very notion of economy.”

The black belt in invective has to go to Cintra Wilson, whose anti-celebrity-culture book A Massive Swelling describes Dion as “the most wholly repellant woman ever to sing songs of love,” singling out “the eye-bleeding Titanic ballad” as well as her “unctuous mewling with Blind Italian Opera Guys in loud emotional primary coloring.” Wilson concluded: “I think most people would rather be processed through the digestive tract of an anaconda than be Céline Dion for a day.”

My personal favorite is the episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer in which Buffy moves into her freshman university dorm and her roommate turns out to be, literally, a demon – the first clue being that she tacks a Céline Dion poster up on their wall. But the catalogue of slams, from critics to Sunday columnists and talk-show hosts to Saturday Night Live, could fill this book. I’ve mostly seconded those emotions, even when a blog ran a Dion joke contest that produced the riddle, “Q: Why did they take the Céline Dion inflatable sex doll off the market? A: It sucked too hard.”

But it was at the Oscars that things got personal.

* * *

The night was the expected Titanic sweep, capped by director James Cameron’s bellowing self-quotation, “I’m the king of the world!” (Which from that podium sounded like, “My brand has total multiplatform synergy!”) But in the Best Original Song category, Titanic – and Dion – had one unlikely rival, and it happened to be Elliott Smith.

Smith was a hero of mine and of the late-90s indie subculture, one of those “literate,” bedroom-recording songwriters whose take on cool and beauty seemed leagues away from the pop-glamour machine. Pockmarked and shy, with a backstory that included childhood abuse and (though I didn’t know it yet) on-and-off heroin addiction, he had recorded mainly for the tiny northwestern Kill Rock Stars label, but had just signed to Dreamworks, which would release his next album, XO, that summer.

Smith wrote songs whose sighing melodies served as bait for lyrics laced with corrosive rage. They dangled glimpses of a sun “raining its guiding light down on everyone,” but everyone in them got burned. They were catchy like a fish hook. As his biographer Benjamin Nugent later wrote in Elliott Smith and the Ballad of Big Nothing, “Smith effectively deploys substance abuse as a metaphor for other forms of self-destructive behavior, and the metaphor is a handy one for several reasons. For one, a songwriter taking substance abuse as his literal subject (even if love is the figurative one) can easily steer clear of the Céline Dion clichés of contemporary Top 40 music, the language of hearts, embraces, great divides. [Instead] he participates in a hipper tradition, that of Hank Williams, Johnny Cash and Kurt Cobain – their addiction laments, disavowals and caustic self-portraits.”

Smith also dealt frankly, I felt, with one of the ruling paradoxes for partisans of “alternative” culture: It might look like you were asserting superiority over the multitudes, but as a former bullied kid, I always figured it started from rejection. If respect or simple fairness were denied you, you’d build a great life (the best revenge) from what you could scrounge outside their orbit, freed from the thirst for majority approbation. This dynamic is frequently rehearsed in Smith’s songs: In “2:45 a.m.,” a night prowl that begins by “looking for the man who attacked me / while everybody was laughing at me” ends with “walking out on Center Circle / Been pushed away and I’ll never come back.” If laments and disavowals were your lot, you would shine those turds until they gleamed. And you’d spread the word to the rest of the alienated, walking wounded – which, in a late-capitalist consumer society, I thought, ought to include everyone but the rich – that they too could find sustenance and sympathy in a voluntary exile.

So how had Smith ended up in center circle at the Shrine Auditorium, smack up against the “Céline Dion clichés,” a juxta-position that seemed as improbable as Gummo winning Best Picture? An accident, really. Years before, he’d met independent filmmaker Gus Van Sant hanging out in the Portland bars where Smith’s first band, Heatmiser, played. That friendship led to writing songs for Van Sant’s first “major motion picture,” Good Will Hunting, and so to Oscar night, featuring (as Rolling Stone put it) “one of the strangest billings since Jimi Hendrix opened for the Monkees,” with Smith alongside the pap trio of Trisha Yearwood, Michael Bolton and Céline Dion.

He tried to refuse the invitation, “but then they said that if I didn’t play it, they would get someone else to play the song,” he told Under the Radar magazine. “They’d get someone like Richard Marx to do it. I think when they said that, they had done their homework on me a little bit. Or maybe Richard Marx is a universal scare tactic.”

(Richard Marx, for those who’ve justifiably forgotten, was the balladeer who in 1989 sang, “Wherever you go, whatever you do, I will be right here waiting for you” – threatening enough? But if Dion hadn’t been booked, her name might have worked too.)

On Oscar night, Madonna introduced the performers. Smith ended up following Trisha Yearwood’s rendition of Con Air’s “How Do I Live?” (written by Dianne Warren, who also penned “Because You Loved Me” and “Love Can Move Mountains” for Dion). He shuffled onstage in a bright white suit loaned by Prada – all he wore of his own was his underwear – and sang “Miss Misery,” Good Will Hunting’s closing love song to depression. The Oscar producers had refused to let Smith sit on a stool, leaving him stranded clutching his guitar on the wide bare stage. The song seemed as small and gorgeous as a sixteenth-century Persian miniature.

And what came next? Céline Dion swooshing out in clouds of fake fog, dressed in an hourglass black gown, on a set where a white-tailed orchestra was arrayed to look like they were on the deck of the Titanic itself. She’d played the Oscars several times, and brought on her full range of gesticulations and grimaces, at one point pounding her chest so robustly it nearly broke the chain on her multimillion-dollar replica of the movie’s “Heart of the Ocean” diamond necklace. Then Dion, Smith and Yearwood joined hands and bowed in what Rolling Stone called a “bizarre Oscar sandwich.”

“It got personal,” Smith said later, “with people saying how fragile I looked on stage in a white suit. There was just all of this focus, and people were saying all this stuff simply because I didn’t come out and command the stage like Céline Dion does.”

And when Madonna opened the envelope to reveal that the Oscar went to “My Heart Would Go On,” she snorted and said, “What a shocker.”

I liked Madonna, who danced on the art/commerce borderline as nimbly as anyone. But right then, I squeezed my fists wishing she’d preserved a more dignified neutrality (“dignified neutrality” being the phrase that springs right to mind when you say “Madonna”). In retrospect, I realize she was making fun of the predictability, not of Elliott Smith; my umbrage only showed how overinvested I was. I wasn’t surprised the Oscars had behaved like the Oscars, that the impossibly good-looking people had spotted each other across the room and as usual run sighing into one another’s arms. But the carnivalesque reversal that wedged Elliott in there with Céline and Trisha was one of those rips in the cultural-space continuum that make you feel anything may happen. I was enough of a populist even then to dream that love might move mountains and heal the great divide.

But when Madonna seemed to chuckle at Elliott Smith, the grudge was back on. And not with Madonna. With Céline Dion.

* * *

Lamentably, this story requires a coda: Elliott Smith had an adverse reaction to his dose of fame. Paranoid that his friends resented him, he distanced himself, relapsing into mood swings and substance abuse, even public brawls. His songwriting suffered, with the so-so Figure 8 in 2000 and then zip until 2003, when he reportedly had sobered up and was finishing a new album. Then, on October 21, 2003, police in Los Angeles got a call from Smith’s girlfriend in their Echo Park apartment. They had been arguing. She had locked herself in the bathroom. Then she heard a scream. She came out to find Smith with a steak knife plunged into his chest, dead at thirty-four.

I hadn’t thought much about the Oscar debacle between 1998 and 2003. I’d moved from Montreal to Toronto, from the alternative weekly to a large daily paper, gotten married (to a woman with a severe Gummo fixation), and settled into a new circle of friends. But the day Smith died, I flashed back to that night when the whole world had gotten to hear what one of its fragile, unlovely outcasts had to offer, and it answered, No, we’d prefer Céline Dion.

“Tastes,” wrote the poet Paul Valéry, “are composed of a thousand distastes.” So when the idea came to me recently to examine the mystery of taste – of what keeps Titanic people and Gummo people apart – by looking closely at a very popular artist I really, really can’t stand, Dion was waiting at the front of the line.

![]()

2

Let’s Talk About Pop (and Its Critics)

I did not hate Céline Dion solely on Elliott Smith’s account. From the start, her music struck me as bland monotony raised to a pitch of obnoxious bombast – R&B with the sex and slyness surgically removed, French chanson severed from its wit and soul – and her repertoire as Oprah Winfrey-approved chicken soup for the consumerist soul, a neverending crescendo of personal affirmation deaf to social conflict and context. In celebrity terms, she was another dull Canadian goody-goody. She could barely muster up a decent personal scandal, aside from the pre-existing squick-out of her marriage to the twice-her-age Svengali who began managing her when she was twelve.

As far as I knew, I had never even met anybody who liked Céline Dion.

My disdain persisted after I left the Céline ground zero of Montreal, and even as my enchantment with “underground” cultural commandments weakened and my feelings warmed to more mainstream music. I can’t claim any originality in that shift. I went through it in synch with the entire field of music criticism, save the most ornery holdouts and hotheaded kids. It came with startling speed. A new generation moved into positions of critical influence, and many of them cared more about hip-hop or electronica or Latin music than about rock, mainstream or otherwise. They mounted a wholesale critique against the syndrome of measuring all popular music by the norms of rock culture – “rockism,” often set against “popism” or “poptimism.” Online music blogs and discussion forums sped up the circulation of such trends of opinion. The Internet pushed aside intensive album listening in favor of a download-and-graze mode that gives pop novelty more chance to shine. And downloading also broke the corporate record companies’ near-monopoly over music distribution, which made taking up arms against the mass-culture music Leviathan seem practically redundant.

Plus, some fantastic pop happened to be coming out, and everyone wanted to talk about it. In a Toronto bookstore in 1999, a bright young experimental guitarist caught me off guard by asking if I had heard the teen diva Aaliyah’s hit, “Are You That Somebody.” I hadn’t, but I soon would. That rhythmically topsy-turvy R&B track was produced by Timothy Mosley, a.k.a. Timbaland, and he and his peers began making the pop charts a freshly polymorphous playground. Après Timbaland, la deluge: critics started noticing a kindred creativity even in despised teen pop, and by 2007, writers at prestige publications like the New York Times and the haughty old New Yorker could be found praising one-hit R&B wonders and “mall punk” teen bands as much as Bruce Springsteen or U2.

This was the outcome of many cycles of revisionism: one way a critic often can get noticed is by arguing that some music everyone has trashed is in fact genius, and over the years that process has “reclaimed” genres from metal to disco to lounge exotica and prog rock, and artists from ABBA to Motorhead. Rolling Stone’s jeers notwithstanding, the Monkees are now as critically respectable as Jimi Hendrix. Even antebellum blackface minstrel music has been reassessed, its melodies as well as its racial pathologies found to lie at the twisted root of American popular song.

This epidemic of second thought made critical scorn generally seem a tad shady: If critics were so wrong about disco in the 1970s, why not about Britney Spears now? Why did pop music have to get old before getting a fair shake? Why did it have to be a “guilty” pleasure? Once pop criticism had a track record lengthy enough to be full of wrong turns, neither popular nor critical consensus seemed like a reliable guide. Why not just follow your own enjoyment? Unless you have a thing for white-power anthems, the claim now goes, there is no reason ever to feel guilty or ashamed about what you like. And I agree, though it’s curious how often critics’ “own enjoyment” still takes us all down similar paths at once.

The collective realignment was also a market correction. After the tumult of the early 1990s, when “underground” music was seized on by the mainstream and just as quickly thrown overboard, many critics and “underground” fans got in a cynical mood. The ever-present gap between critica...