![]()

1

A Therapeutic Value for City Dwellers: John Cage’s Early Avant-Garde Aesthetic

In the sixth of ten interviews conducted by Daniel Charles, John Cage recollected a signature moment in his acquaintance with the painter Mark Tobey:

One day we were taking a walk together, from the Cornish School to the Japanese restaurant where we were going to dine together—which meant we crossed through most of the city. Well, we couldn’t really walk. He would continually stop to notice something surprising everywhere—on the side of a shack or in an open space. That walk was a revelation for me. It was the first time someone else had given me a lesson in looking without prejudice, someone who didn’t compare what he was seeing with something before, who was sensitive to the finest nuances of light. Tobey would stop on the sidewalks, sidewalks which we normally didn’t notice when we were walking, and his gaze would immediately turn them into a work of art.1

While this is not one of Cage’s most frequently recounted stories, it is typical of him for the manner in which actual events become, in the telling, parables of his artistic development. The setting is Seattle, where Cage had relocated in the fall of 1938 to take a faculty position at the Cornish School.2 This move marked an important turning point in Cage’s career, largely coinciding with the abandonment of his interest in serial composition in favor of the percussion music that linked him to the “experimental” wing of the musical avant-garde.3 Throughout the following decade, in ways both explicit and subtle, Cage would investigate a host of earlier avant-garde ideas, adopting and adapting them for his own ends in what amounts to an important chapter not only in his own development but also in the broader history of the European avant-garde’s translation into the American context. Standing behind Cage’s account of his cross-town trek with Tobey is a much wider array of engagements with the legacies of futurism, dada, the Bauhaus, and the much lesser-known movement verticalism, associated with the editors of transition magazine. Initially turning the insights gained from such historical avant-garde precedents toward the goal of an anonymous and collective musical practice, Cage would become motivated by a growing antipathy toward American commercialism and conformity to seek an aesthetic that promoted social cohesion while increasingly valuing and respecting individual difference.

*

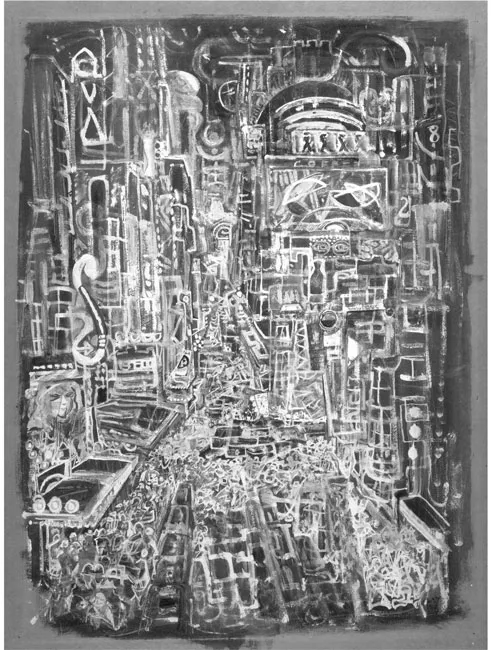

Within the avant-garde of the late 1930s, stories of an artist like Tobey hoping to modify an individual’s perception of the contemporary urban environment were already familiar.4 Tobey must have been a particularly good companion for Cage’s walk through the city, as the modern metropolis was one of the painter’s most significant artistic stimuli. Inspired by New York’s Broadway, which he first committed to canvas in 1935, Tobey developed an abstracted, calligraphic style of painting to evoke the city’s energy and dynamism (Figure 1.1).5 This was not an environment that the young Cage had previously viewed with any sympathy. Writing to his former teacher Adolph Weiss, a few months after returning from New York to California in 1935, he lamented, “Somehow I am very sad that you are staying in New York. It is rarely that fine things come out of immense cities. Rather, it seems to me, reality is sucked in there and becomes unreal, meaningless.”6 It took Tobey’s example (and the much less imposing metropolitan environment of Seattle) to open Cage to an “unprejudiced” vision of such things as urban shacks, alleyways, and sidewalks. Yet, however important Cage’s revelation with Tobey, it must have served primarily as a reinforcement of the futurist-inspired aesthetic that he was already pursuing.

Figure 1.1 Mark Tobey, Broadway, 1935–36.

In the decade following his move to Seattle, Cage’s principal artistic concern was to accommodate the modern individual to his or her social and environmental conditions, conditions which included not only the city’s physical surroundings, but also the increasing development of social atomization. The dissolution of community and the cultural traditions by which it was marked had been of concern to Cage since the early 1930s, and as he looked out across the musical landscape he saw two predominant reactions to it. The first consisted of a retreat into traditionalism, an embrace of neo-classicism which Cage rejected out of hand, denigrating those whom he would accuse of “spend[ing] their lives with the music of another time, which, putting it bluntly and chronologically, does not belong to them.”7 Cage also openly disapproved of composers who modernized their subjects without consequently modifying their form, lending a superficially progressive or revolutionary air to otherwise traditional work. As Cage wrote disdainfully, “When this better social order is achieved, their songs will have no more meaning than the ‘Star-spangled Banner’ has today.”8

The second camp that Cage perceived consisted of modernists who sought to develop musical form but did so by such individualistic means as to reflect, or even exacerbate, the phenomenon of social fragmentation. In the article “Counterpoint” of 1934, the twenty-two-year-old Cage lamented “the relative absence of academic discipline and the presence of total freedom” in contemporary music.9 “Modern Music,” he argued, did not properly exist, being only a heterogeneous grouping of more or less distinct individual styles. After listing and briefly discussing some of them, Cage called for the creation of a new, universal style appropriate for the age:

I sincerely express the hope that this conglomeration of individuals, names merely for most of us, will disappear; and that a period will approach by way of common belief, selflessness, and technical mastery that will be a period of Music and not of Musicians, just as during the four centuries of Gothic, there was Architecture and not Architects.10

The contemporary situation was thus a dichotomous one in which musical production accurately reflected the dissolution of social cohesion. While the first reaction, neo-classicism, provided tradition and community at the cost of modernity, the second achieved modernity only by sacrificing a common aesthetic structure. This situation forms the background against which Cage’s early avant-garde program developed.

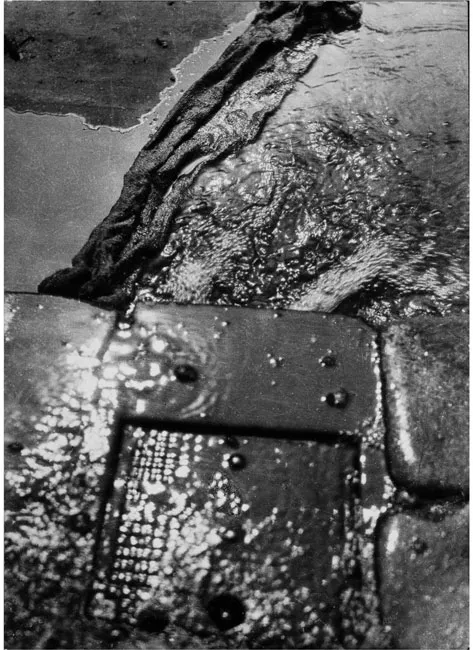

Although Cage found affinities between himself and Tobey, his early artistic orientation was more closely allied with the work of former Bauhaus instructor László Moholy-Nagy whom he had met while teaching at Mills College in the summer of 1938.11 Moholy-Nagy was one of the early practitioners of perceptual estrangement, the depiction of new and unfamiliar perspectives of the world in order to counteract outworn perceptual modalities. Decades before Tobey achieved his mature style, Moholy-Nagy was already using photography to create such effects. A Moholy-Nagy image such as that of a Paris street-side drain shot from above and close-up fulfilled a similar function of perceiving the mundane anew as Tobey’s pedagogical walk with Cage (Figure 1.2). Yet, while both experiences focused perception onto previously unseen aspects of the urban environment, Moholy-Nagy’s explicit desire to modernize the individual’s perceptual capabilities more closely matched Cage’s early interests.12 By the time of their meeting Cage had likely already encountered Moholy-Nagy’s Von Material zu Architektur, the English title of which, The New Vision, succinctly summarized its author’s artistic program. Cage, who later described The New Vision as “very influential for my thinking,” would work toward essentially the same objective as Moholy-Nagy, which, as Sigfried Giedion summarized it, was “to bridge the fatal rift between reality and sensibility which the nineteenth century had tolerated, and indeed encouraged … to give an emotive content to the new sense of reality born of modern science and industry; and thereby restore the basic unity of all human experience.”13

Figure 1.2 László Moholy-Nagy, Gutter [Street Drain (Rinnstein)], 1925.

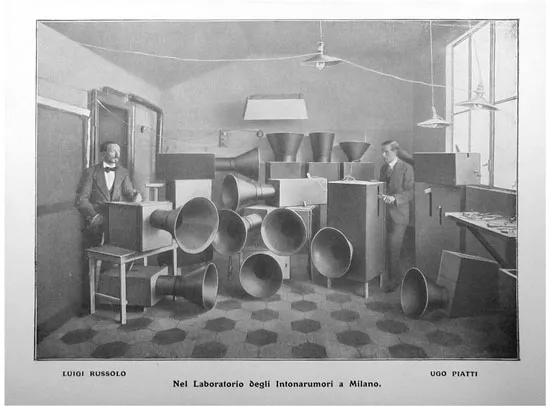

In order to achieve the goal of modernizing auditory perception, Cage allied himself with music’s futurist and ultramodernist lineage, which included Luigi Russolo, Edgard Varèse, George Antheil, and Henry Cowell. Although all of them would be important for Cage’s development (some, as in the case of his former teacher Cowell, more than he tended to acknowledge), he placed particular emphasis on Russolo, the Italian futurist author of The Art of Noises (Figure 1.3).14 However Cage came upon Russolo’s manifesto, he began invoking it soon after arriving in Seattle, explaining for example that “Percussion music really is the art of noise and that’s what it should be called.”15 Further affinities arise in Cage’s “The Future of Music: Credo,” where phrases of Russolo’s such as “We must break out of this limited circle of sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds” are echoed in its first lines: “I believe that the use of noise to make music will continue and increase until we reach a music produced through the aid of electrical instruments which will make available for musical purposes any and all sounds that can be heard.”16

Figure 1.3 Luigi Russolo, in his laboratory of noise instruments, with Ugo Piatti, 1916.

Russolo would have been important to Cage not only for providing indications of a futurist musical practice, but also for describing the musical equivalent of perceptual estrangement.17 In characterizing the state of modern composition, Russolo spun an apocryphal tale of music’s development into an autonomous, transcendental realm:

Among primitive peoples, sound was attributed to the gods. It was considered sacred and reserved for priests, who used it to enrich their rites with mystery. Thus was born the idea of sound as something in itself, as different from and independent of life. And from it resulted music, a fantastic world superimposed on the real one, an inviolable and sacred world.18

Unfortunately, Russolo argued, this old, “sacred” realm of music had degenerated into irrelevancy, its sounds losing their exotic and awe-inspiring character and becoming so familiar as to seem, for a futurist at least, deadeningly boring.19 In contrast, the use of noise served two interrelated functions: (1) it negated the sacred space of music’s circumscribed sound field, thereby freeing listeners from their habitual perceptual modalities; and (2) it called attention to modern acoustical experiences. As Russolo explained,

Every manifestation of life is accompanied by noise. Noise is thus familiar to our ear and has the power of immediately recalling life itself. Sound, estranged from life, always musical, something in itself, an occasional not a necessary element, has become for our ear what for the eye is a too familiar sight. Noise instead, arriving confused and irregular from the irregular confusion of life, is never revealed to us entirely and always holds innumerable surprises.20

Cage adopted Russolo’s understanding of noise as a means of jolting the listener out of his or her habitual acceptance of traditional, outworn sounds. Reinfo...