eBook - ePub

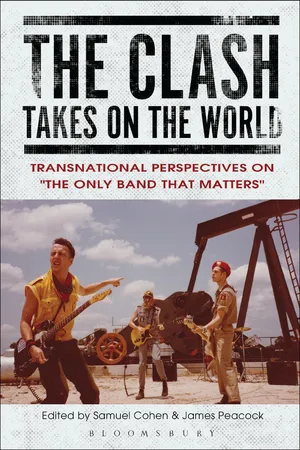

The Clash Takes on the World

Transnational Perspectives on The Only Band that Matters

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Clash Takes on the World

Transnational Perspectives on The Only Band that Matters

About this book

On their debut, The Clash famously claimed to be "bored with the USA," but The Clash wasn't a parochial record. Mick Jones' licks on songs such as "Hate and War" were heavily influenced by classic American rock and roll, and the cover of Junior Murvin's reggae hit "Police and Thieves" showed that the band's musical influences were already wide-ranging. Later albums such as Sandinista! and Combat Rock saw them experimenting with a huge range of musical genres, lyrical themes and visual aesthetics.

The Clash Takes on the World explores the transnational aspects of The Clash's music, lyrics and politics, and it does so from a truly transnational perspective. It brings together literary scholars, historians, media theorists, musicologists, social activists and geographers from Europe and the US, and applies a range of critical approaches to The Clash's work in order to tackle a number of key questions: How should we interpret their negotiations with reggae music and culture? How did The Clash respond to the specific socio-political issues of their time, such as the economic recession, the Reagan-Thatcher era and burgeoning neoliberalism, and international conflicts in Nicaragua and the Falkland Islands? How did they reconcile their anti-capitalist stance with their own success and status as a global commodity? And how did their avowedly inclusive, multicultural stance, reflected in their musical diversity, square with the experience of watching the band in performance? The Clash Takes on the World is essential reading for scholars, students and general readers interested in a band whose popularity endures.

The Clash Takes on the World explores the transnational aspects of The Clash's music, lyrics and politics, and it does so from a truly transnational perspective. It brings together literary scholars, historians, media theorists, musicologists, social activists and geographers from Europe and the US, and applies a range of critical approaches to The Clash's work in order to tackle a number of key questions: How should we interpret their negotiations with reggae music and culture? How did The Clash respond to the specific socio-political issues of their time, such as the economic recession, the Reagan-Thatcher era and burgeoning neoliberalism, and international conflicts in Nicaragua and the Falkland Islands? How did they reconcile their anti-capitalist stance with their own success and status as a global commodity? And how did their avowedly inclusive, multicultural stance, reflected in their musical diversity, square with the experience of watching the band in performance? The Clash Takes on the World is essential reading for scholars, students and general readers interested in a band whose popularity endures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Clash Takes on the World by Samuel Cohen, James Peacock, Samuel Cohen,James Peacock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Música punk. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Analysis of The Clash in Concert: 1977 to 1982

Peter Smith

Introduction

This chapter presents a reflective analysis of The Clash in concert, taking me on a journey through a few short years, beginning in 1977 when I stood in awe, amazed at the raw power of the band on the White Riot tour, through to the last time I saw a disintegrating Clash in 1982. As a veteran concertgoer and a researcher, I use my research training to critically examine my encounters with The Clash, drawing from my own memories and experiences, cultural studies theory, fan sites and reviews from music papers of the day. I focus my analysis on the following interlinked themes: tension and violence in the performances and the audience, the clash between the band’s values and the reality of the performances, and ‘cultural conflict’ in all aspects of the performances. I also reflect on the importance of the concerts in the development of the punk subculture within the northeast of England. To do so I use Vallack’s methodology for valid, first-person research located within phenomenology (Vallack 2010) alongside Auslander’s schema for performance analysis (Auslander 2004) to explore the performances.

My analysis is drawn from the following five UK concerts, which I personally attended: an awesome, frantic gig when the White Riot tour called at Newcastle University in May 1977, which gave young people in the north-east of England their first chance to experience live punk rock and which was marred by violence when local punks were denied entry to the student-only gig; concerts at Newcastle Polytechnic in October 1977 and December 1978, which were joyous, uplifting experiences, yet also suffered from some serious crowd violence; a gig at Newcastle Mayfair in June 1980 where The Clash returned to the Northeast as rock heroes; and a concert at Newcastle City Hall in July 1982 when The Clash were starting to fall apart. For each concert I will examine the performance, the support acts, the audience, the venue and the context, exploring the seeming paradox between the inclusive and multicultural values of the band and how this translated into reality through performance, and the violent clashes (of culture and actual physical violence) which erupted at several of those performances. Jonathan H. Turner (2005) defines ‘cultural conflict’ as a conflict caused by differences in cultural values and beliefs that place people at odds with one another. Cultural conflicts are complex and difficult to resolve and they intensify when the differences in value become reflected in politics. In this study, I explore the manifestation of cultural conflict in the punk scene in relation to the wider sociopolitical climate of Northeast England in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The following approach was taken: first I wrote narrative accounts of my memories of the concerts, recalling as much detail as I could. I then immersed myself in the literature relating to the period, reading academic papers discussing the emergence of punk culture in 1976 and 1977 and reviews from music papers of the time. I then reread my narrative accounts and performed an initial analysis of the performances, using an approach based on the schema of Auslander (2004), which analyses performance according to several different dimensions (including performer, audience, and social context) to identify initial themes. Having immersed myself in the data, and performed my initial analysis, I left the material as recommended by Vallack (2010), allowing time for further reflection. After a short period of quiet reflection, I returned to complete the analysis, drawing out my final thoughts in the form of metaphor. Vallack argues that her methodology presents an approach to deeper objectivism through which universal insight can be achieved; the derivation of metaphor or imagery facilitates a transcendental transformation through which the subjectivism of first-person research data may reveal deeper, more universal meaning. For each concert, I derived a metaphor, as recommended by Vallack, which I used as a vehicle for the final analysis and discussion.

I recognize the autobiographical nature of this account, and the limitations of my approach. Medhurst (1999) writes of the danger of the ‘I was there’ approach and how emotion and personal connections to events and memories can dampen critical analysis. However, Turrini (2013) argues that alternative approaches such as the narrative and oral history (as used by Robb 2006) are suited to the analysis of punk. Turrini analyses a series of oral histories of punk rock, and argues that their format is similar in approach to punk culture and that they are being used to create collective memory. He concludes that these elements make oral history particularly suitable for the analysis and exploration of punk. In line with Turrini, I take my own recollections as a departure point from which to investigate this collective culture.

I started going to concerts in the late 1960s, and was a big fan of many different genres of live music. If you’d asked me in 1976 who my favourite bands were, I probably would have said The Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Uriah Heep, The Groundhogs and Yes. I wore flares, a cheesecloth shirt, and had hair down my back, so I wasn’t your typical punk. However, in 1976 I saw The Sex Pistols, everything changed, and I started to wear drainpipe Levi jeans, Denson winkle-picker Chelsea boots and a leather biker jacket (although my hair stayed long).

Some 250 miles north of London, the northeast of England was geographically and culturally removed from the massive changes in youth culture that were taking place in the South during 1976 and 1977. The traditional industries of shipbuilding and coal mining were in decline, and young people were restless. For many, the London music scene might as well have been a million miles away; however, we were aware, largely through the weekly music press, of the new movement. Cobley writes of the ‘insidious myth’ that punk was an entirely London phenomenon (1999: 170), and points out that Jon Savage’s definitive account of the growth of punk culture (Savage 1991) continues to perpetrate the myth. Cobley gives an account of what it was like to be a punk in Wigan in 1977. The bricolage and DIY culture in these areas was born out of necessity rather than ‘post-Westwood confrontation dressing. … The unspectacular nature of punk in the provinces during the late 1970s is, in fact, due to a different and very real threat: other citizens, often working class men, who engaged in repressive coercion rather than a Gramscian winning of consent’ (1999: 172). The Casino punk nights from eight till midnight were directly followed by the regular soul all-nighter crowd, a tradition that positioned the punks as outsiders, leading to stabbings happening directly outside the club. Cobley explains that it was not hard to provoke onlookers and suggests that the more subtle tones of the punk aesthetic in Wigan were due to a hostile and often aggressive response to non-conformism, leading to individuals choosing to get changed into their punk gear in the toilets of venues to avoid confrontation: ‘It was one thing to be a spectacular punk rocker in the safety of a club in central London, and quite another to attempt to be one in a small provincial enclave’ (Cobley 1999: 172). In a similar way, and with similar dangers, the punk revolution was starting to be felt in the Northeast. Our first opportunities to experience what ‘punk’ really meant came through going to early gigs, such as when The Clash first came to the region during the White Riot tour.

The Clash White Riot tour Newcastle University 20 May 1977

The Fifth Wall

Support acts: The Slits, Subway Sect and The Prefects

The Fourth Wall is the imaginary ‘wall’ at the front of the stage in a traditional three-walled theatre, through which the audience sees the action (Bell 2008: 203). At this concert, I experienced a ‘Fifth Wall’ – that which divided those outside the venue, and wishing to gain entrance, from those inside the hall attending the concert. The Fourth Wall (that imaginary wall between the audience and The Clash) and the Fifth Wall are focal points to which I return within my analysis.

Newcastle upon Tyne was a major coal mining area, and its port housed one of the world’s largest shipyards. By 1977, both of these industries were in decline. Newcastle University can trace its origins to a School of Medicine, established in 1834: hardly a venue for punk rock. This was the night that punk truly arrived in Newcastle, and the first time I saw The Clash. It was the first really big punk gig in Newcastle (The Sex Pistols never did play in the city) and sold out well in advance. Sadly, most of the tickets had gone to students, and not to the working-class kids at whom The Clash’s music was aimed. You had to be a student to buy tickets; I was at Sunderland Polytechnic at the time and I used my union card to buy tickets. When we arrived at the Union building on the night of the gig, the entrance was surrounded by a group of local punks trying to get in (through the Fifth Wall). There were scuffles between the doormen and the punks who were angry because they couldn’t see ‘their band’ who (in their eyes) were playing for a group of middle-class students. This went on throughout the night. Mensi, soon to form the Angelic Upstarts, was present that night (Robb 2006), and would write the song ‘Student Power’ about the chasm between the students and the punks. The small door, which marked the entrance to the students’ union building, became a focal point for the Fifth Wall and for violence throughout the night. The punks outside were pleading with the doormen to let them in; that pleading soon changed to violence as the evening progressed and as the growing crowd tried to force their way into the gig. At one point, Joe Strummer and other members of The Clash came to the door and ordered the staff to let some fans in: ‘I had a ticket but couldn’t get in initially as I wasn’t a student but Strummer and co. came to the door and we were all l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction: The Transnational Clash

- 1 An Analysis of The Clash in Concert: 1977 to 1982 Peter Smith

- 2 Politics, Pastiche, Parody and Polemics: The DIY Educational Inspiration of The Clash Andy Zieleniec

- 3 Turning Rebellion into Money: The Roots of The Clash Lloyd I. Vayo

- 4 The Clash Sell Out: Negotiating Space in the Ideological Superstructure Nathalie Prévot and Graham Sinclair

- 5 The Clash: Sociological Imagination and Critical Philosophy Diana Cedeno

- 6 Righteous Minstrels: The Clash, Race and the Rock Writer Jack Hamilton

- 7 Washington Bullets: The Clash and Vietnam Samuel Cohen

- 8 Spouting Slogans for the Sandinistas? The Clash and International Solidarity Jeremy Tranmer

- 9 Punk Politics, Blackness and Indigenous Protest: The Clash’s Australian Tour, 1982 Gabriel Solis

- 10 From a Long Way Away: New York and London in The Clash’s ‘Red Angel Dragnet’James Peacock

- 11 The Last Gang in Town: The Clash Portrayed in New York and Paris Justin Wadlow

- 12 Mick Went Disco and Joe Sang Campfire Songs: Punk After-parties and the Politics of Forking Paths Michael J. Salvo

- Conclusion: The Only Band that Matters Samuel Cohen and James Peacock

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Copyright