![]()

CHAPTER ONE

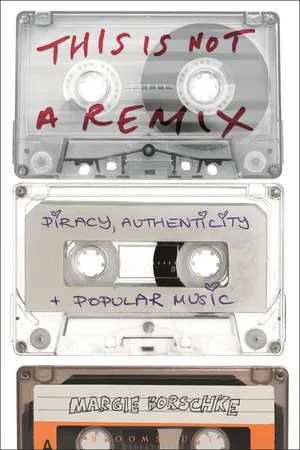

This is not a remix

1.1 Introduction

Kim Dotcom’s arrest in 2012 was just like a movie: helicopters swooped in; hounds were unleashed; and semi-automatic weapons were waved in the air, wielded by the New Zealand police who stormed into the rural mansion where the Megaupload billionaire, his wife, three children, and house guests were sleeping. On the day before his thirty-eighth birthday, Dotcom was charged with numerous offences including copyright infringement, racketeering, money laundering, and piracy.

A few hours before the raid, the American Federal Bureau of Investigation, who orchestrated the police operation, seized MegaUpload’s servers at a data center in Europe. Precisely what was on these servers is unknown—at the time the cloud-based file hosting service had approximately 180,000,000 registered members—but in the aftermath, there were anecdotal reports from users claiming that several significant and admired American MP3 bloggers, aficionados of the obscure and forgotten, were among those who lost access to their data. Just like that, their collections were wiped clean.

Internet outrage ensued. Fans held up the bloggers as latter day Alan Lomaxes, people who collected and harvested songs in the name of posterity and cultural knowledge, in some cases working in tandem with the overlooked and rediscovered artistic geniuses that they loved. Posting on WFMU’s Beware the Blog that week, Jason Sigal (2012) wrote, “The best music blogs aren’t pirates. They are libraries, sound archivists and music preservationists sharing recordings that would not otherwise be available. And now sites like Global Groove, Mutant Sounds and Holy Warbles have lost large swaths of the material they’d salvaged from obscurity.” After tweets of outrage and posts of fury, listeners from around the world swiftly began the work of reassembling the collections, relying on the very action that made them exist in the first place: they posted their copies to the Internet and the copying began anew.

Same as it ever was.

Even so, the influence of the MP3 blog on popular music culture began to fade and the enthusiasm of its most enthusiastic participants waned. The chilling effect of the Dotcom raids and other antipiracy efforts took its toll. Simultaneously, streaming sites like Spotify and Apple Music produced yet another change in listening habits, away from the downloading, collecting, and the virtual hoarding that characterized the first decade of the twenty-first century, towards on-demand streaming and “social” listening; vinyl made its notorious comeback in the mainstream media; and even the most ardent free culture evangelists began to wonder about the human cost of the so-called “sharing economy.” And yet, while more industry-friendly practices and technologies may seem to shift priorities away from the copy, copying remains functionally essential, one of the central practices of digital culture. Likewise, recordings (qua copies) are still the animating artifact in popular music cultures. The sea of big data is fed by a river of copies and, to paraphrase Heraclitus’s ancient paradox, you still cannot step twice into the same stream.

Again and again, we see culture transformed and sustained by reproduction and repetition. This book considers the relationship between media and culture, by focusing on the social and material histories of copies and their circulation. As Jussi Parikka (2008: 73) has noted, “The material processes of copy routines have often been neglected in cultural analysis, but the juridical issue of copyright has had its fair share of attention.” In this monograph, I offer an argument not about the regulation of copies and copying, but about their poetics, highlighting the material, rhetorical, social, and cultural dimensions of copies and aesthetic dimension of distribution and circulation, both now and in the past. Copy is concept that requires critical investigation. We must simultaneously consider “copy” as a relational property of objects, but also as a concept and practice that has a history, one that is intermingled with the particular histories of different technologies of representation, reproduction, and exchange. Particular cultural histories offer answers to questions about the role of media technology in cultural change, and in this book I recount and resurrect neglected material histories to consider what a study of copies can tell us about the relatively recent transition from analog to digital reproduction in music culture and the intersection of this shift with the rise of network culture and the ability to distribute, discuss, and connect musical artifacts, knowledge, and communities of listeners. I argue that we can better understand this transition if we focus not only on regulatory questions pertaining to copyright, but also on aesthetic questions related to the status of sound recordings as copies and the materiality of media technologies and formats as well as their rhetorical weight.

To ask questions about the present, I look to media’s recent past and ask, in turn:

•Why copies now?

•Why remix now?

•Why vinyl now?

•Why redistribution now?

Some of my answers to these questions, I hope, will help carve out a space for talking about the aesthetics of circulation within media studies and in our wider history of ideas.

1.2 Critical approach

This study approaches questions about media technology and cultural change through a focus on media artifacts as copies, and thus takes an interest in similarities and continuities as well as difference. I believe a focus on copies can do two things: It can help us understand media artifacts as objects that have material, social, and cultural histories, and it can help expand how we use them to understand our world and express our place within it. I begin with the assumption that since the twentieth century, cultures of popular music were also recorded music cultures (Hennion 2001, 2008; Toynbee 2000), and that, within these popular cultures, copying practices were often more common than they were controversial. Yet, we also know that in discussions about copyright and use, digital replication, sampling, and the distribution of sound files via peer-to-peer technologies or websites are flash points for debate. Many critiques of copyright raise concerns about the policy’s possible overreach in an era of digital technologies. These concerns are well documented and discussed across disciplines (e.g., Berry 2008; Berry and Moss 2008; Coombe 1998; Lessig 2002, 2004, 2008; McLeod 2007; McLeod and DiCola 2011; Vaidhyanathan 2003), and such scholarship often cites the history and importance of musical borrowings and reuse in many of the twentieth century’s most cherished innovations in popular music, and uses these histories in the service of arguments about the possible effects that the expansion of copyright can have on free expression and competition. Stories about the collaborative origins of blues and folk music, as well as potted histories about the origins of Jamaican dub and New York hip-hop, are now on heavy rotation in scholarship that aims to defend digital copying practices and remix culture.

This repetition of a canon of birth narratives serves a rhetorical function as well as an explanatory, or descriptive, one. My concern is that our discussions about what one ought to do with copies and reproduction technologies may be overshadowing our understanding of what people are actually doing now, or what they have done in the past. “Remix,” a term borrowed from audio production and dance music, is now used rhetorically to describe and defend digital practices of copying and recombination. This metaphorical usage, however, in its zeal to defend current networked media use, overshadows the form’s own history and overlooks the material dimensions of that history and the agency of the media users who participated in that history.

In my own experience, and among my peers, the use and “misuse” of technologies of reproduction didn’t start with digital technologies and networks. Rather, digital practices were linked to earlier reproduction practices, such as my own crude efforts to tape songs off the radio (an experience so common that it is now used to evoke 1970s and 1980s nostalgia in television ads) or those of my more sophisticated friends who made masterful mix tapes filled with tracks that radio stations never played, carefully chosen from their beloved collections of records, tapes, and (eventually) CDs. To many music lovers of a certain age, the cries from music-industry associations about peer-to-peer technologies were familiar, sounding an awful lot like the “home taping is killing music” campaigns we ignored and snickered at in the 1980s. Our own experiences with small-scale replications in our bedrooms and living rooms, and their use in social and cultural situations, were pleasurable—perceived as innocent, even—and no doubt shaped how we approached and used new technologies of replication, and, in turn, how we felt about them. The mass domestication of computers and high-speed digital networks changed the scale and reach of these practices and disrupted business models and industrial hierarchies. Yet, industry actions to prevent consumers from using the technologies at their fingertips in the 2000s seemed to only inflame existing antagonisms toward the corporate music industry, and debates over the replication of copyrighted material became increasingly polarized as both “sides” claimed the moral high ground. The question became: Who was killing music, and who was supporting it?

The dichotomy is a false one, but as I looked closer, in between the rhetoric about stealing versus sharing, producers’ rights versus consumers’ rights, and original artists versus parasitic pirates, I began to observe two intriguing undercurrents in arguments about copies and digital networks:

1The arguments that vilified copying practices and those that valorized them appealed to the same romantic ideals of creativity and self-expression when demonizing or defending downloading and file-sharing practices.

2In addition to appeals to ethical principles and arguments about the intentions of copyright as a policy, media users were also presenting aesthetic and social justifications for copies and copying as well as for their control.

These aesthetic and social justifications struck me as a rich area of inquiry, one that would potentially illuminate the conceptual questions I had about the historical relationships between copies and cultures. If we want to understand the cultural consequences of technologies whose functioning is dependent on replication, as digital and network technologies are, we need to be able to account for digital copies as material artifacts and copying as a social practice, while simultaneously accounting for their histories and how they do and don’t shape their current use. That is to say, the material and social dimensions of reproduction is shaped both by copies as an historical phenomenon and copies as an abstraction or transhistorical possibility. To do this, we need a cultural poetics of copies, one that can help us make sense of the recursive relationship between media and culture and decipher some of the contradictions and tensions that characterize the human experience. A poetics of copies and networks would have to grapple not only with legal and political issues, but also with how copies have functioned historically, rhetorically, and materially. It would have to grapple with use as a generator of meaning, as something that was shaped, but not determined by, its history and material makeup, and the rhetorical, as well as the aesthetic, uses to which it is put. It would have to acknowledge the place of the media object and its material dimensions, as well as the place of the media practice, in understanding cultural change.

The central problem then is how do media objects as copies shape media practice, and vice versa? This problem prompts a number of related, big-picture questions including

•How can something that is just the same bring something new into being?

•How do some things become the background for other forms? (Acland 2007: xx)

To approach these questions, this study necessarily operates on several levels: material, formal, rhetorical, and historical. It takes an interest in questions about the relationship between form and format as they relate to the materiality of media and its use. It is also concerned with how we talk about these forms and formats, what we think they mean, and what we believe they can and cannot do. Issues of form and rhetoric are clarified by a consideration of the histories of each, and a focus on copies and copying in popular music practice highlights material, social, and cultural continuities and changes. Throughout this study, I recover lesser-known historical narratives, the analog antecedents to digital phenomena as well as persistent forms and formats, and use them to illuminate contemporary problems and issues and to highlight the (often overlooked) material contours of particular innovations in form and function.

Digitization and networking are issues for all cultural artifacts and systems of communication, not just for musical ones. I chose to focus on popular music not only because it has been at the forefront of battles over copyright (which brings questions about copies to the fore), but also because it has historically proved itself to be an important source of innovation with regard to copying technologies, artifacts, and practices. Music provides an ideal field in which to test questions about copies and replication because repetition and reproduction operate on so many different levels in musical culture. Repetition is a feature of all music (Middleton 1999), and sound recordings as reproductions are the central focus of nearly all music cultures since the early twentieth century (Hennion 2001, 2008; Toynbee 2000). Copies and copying feature in the crystallization of popular music genres (Toynbee 2000). They are listened to and collected by individu...