![]()

1

Introduction

I think one of the main reasons why the videogame business has been so horribly stunted in its growth is that it has been unwilling to look beyond itself to its audience.

Brenda Laurel (2001, 36)

While completing graduate degree work in theater in the 1970s, Brenda Laurel did what many students do: She picked up a job. In Laurel’s case, she took a position as a software designer and programmer at CyberVision producing interactive fairytales. The work drew on Laurel’s growing interest in interactive theater and storytelling, but more importantly, it helped launch her on a career trajectory that took her through stints at leading game companies like Atari and Activision to consulting work with major names in games and media more broadly, such as LucasArts, Apyx, Brøderbund, Paramount New Media, Apple, and Sony Pictures, among others. In 1986, she completed her PhD with a dissertation that drew heavily on her immersive storytelling work at Atari Research Labs, and in 1988 she co-founded the Game Developers Conference.

By the early 1990s, Laurel entered her second decade in the games industry when she accepted a job at Interval Research Corporation, a lab and tech incubator founded by Paul Allen and David Liddle. There, Laurel oversaw a multi-year study to understand the relationships between gender and technology among children and youth, research that became the spinoff company Purple Moon. As co-founder and VP of Design at Purple Moon, Laurel combined her extensive industry experience both as designer and as manager with her training and expertise in theater. Purple Moon was among the most visible of a number of “games for girls”-targeted start-ups in the 1990s. The “games for girls” movement was—and remains—a critical intervention into a games industry that had, by the early 1990s, come to overtly cater to a consumer base made up almost entirely of boys (King and Douai 2014, 4). While Laurel’s published games are also innovative, the very act of taking girls seriously as a potential audience for games was already in and of itself revolutionary. Laurel and her company Purple Moon were at the vanguard of seismic shifts within the game industry. By connecting with and catering to tween girls, Laurel and Purple Moon were at the forefront of exploring what the industry might look like if it looked outside itself to consider the particular needs and desires of the audience. Laurel’s commitment to design research drove innovation at Purple Moon and continues to influence audience-centric approaches to game design. This is particularly true given Laurel’s more recent work creating and leading multiple graduate programs in design. As the games industry is publicly struggling with efforts to diversify in-game representation, audience appeal, and even its workforce, Laurel’s decades of work—as designer, as theorist, as executive, as educator, and as advocate—offer a powerful example of how interdisciplinary thinking, design research, and a willingness to take risks can lead to successful interventions and innovations.

From stage to monitor

Laurel’s design work traces a rich, interdisciplinary path that crosses between the academy and industry. When she began working at CyberVision, Inc. in 1977, she was still in the process of completing her graduate studies. After leaving CyberVision, she worked at a number of Silicon Valley companies, including time spent as a Research Staff Member at Atari’s Sunnyvale Research Lab (1982–1984), and as Director of Product Development for Learning and Creativity at Activision (1985–1987). In 1986, Laurel completed her PhD in Theatre from The Ohio State University. Her dissertation “Toward the Design of a Computer-Based Interactive Fantasy System” drew on drama theory as well as her work at Atari Labs; it is a clear example of the degree to which her academic training in theater and research forms a palimpsest with her industry experience. Her work for Interval and later at Purple Moon relies on this particular context of training and experience.

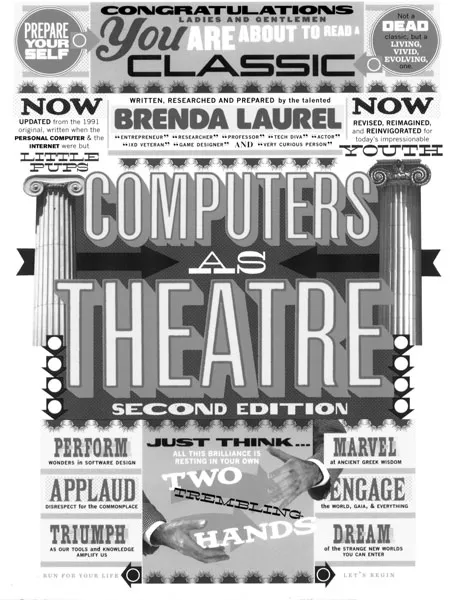

Laurel’s theoretical and critical work also draws on a set of insights from both academic and industry perspectives. Her book Computers as Theatre (first released in 1991 and re-issued in 2013; see Figure 1.1) has become a classic in the field of human–computer interaction (HCI). It relies heavily on her dissertation research and is a crash course in drama theory for the uninitiated mixed with practical examples of how theoretical concepts can usefully inform design projects. For her second book, Laurel turned to a reflection on her own industry experience. Both more personal and more reflective, Utopian Entrepreneur details her own entrepreneurial experiences in games, multimedia, virtual reality, and dot-coms and provides a practical guide for others interested in producing positive social change in the context of for-profit business. While providing a guidebook for others who might wish to follow a similar path, Laurel offers significant insights into her own career, which has been driven by a belief that businesses can do good and enact change in meaningful ways. In these books, Laurel demonstrates her willingness to cross-pollinate fields, to mix HCI with Aristotle, or to infuse entrepreneurial pursuits with a commitment to social justice.

Figure 1.1 The cover design of the 2013 edition of Computers as Theatre invokes the dramatic arts.

This interdisciplinarity and hybridization is fundamental to Laurel’s approach and is a key part of what makes her work innovative and important. It is visible in her training, but the culmination and result is not her training, but her finished work, which has proven influential not only to game design, but also to design research, entrepreneurship, and efforts to ensure diversity in technical fields. For Laurel, game design was not an end in and of itself but rather a potential means of addressing a complex social problem through the production of popular culture. In this way Laurel’s game design work is intimately bound with her work as a researcher-practitioner and her desire to further social good. Game design, in Laurel’s hands, is not a practice, but a praxis—an opportunity to fully realize the potential of her work as a researcher.

Drawing from the notion of game design as a critical research praxis, I consider the extent to which Laurel’s research drives her own design work and subsequently illuminates her ongoing influence as a designer. In this chapter, I interrogate both Laurel’s research-driven approach to design as realized at Purple Moon and her books Computers as Theatre and the memoir-fueled Utopian Entrepreneur. Throughout, I consider the ethos of Laurel’s work as expressed in the books and as evidenced through her game design work. In unpacking Laurel’s writings on design and entrepreneurship and placing them in a context of her design praxis, I argue that Laurel’s innovations in game design emanate from her diverse professional and intellectual background. These experiences are critical to understanding Laurel’s work and are central to her vision as a designer.

Researching games for girls

By the 1980s, video games in the United States were already strongly associated with boys (Kocurek 2015, xiv). And as late as 1998, boys made up 75–85 percent of the industry’s consumers (Cassell and Jenkins 1998, 11). The reasons for this are diverse, including lack of diversity in the industry workforce, gendered notions of childhood, advertising strategies, and numerous other issues (Jenkins 1998; Kocurek 2015; Potanin 2010). In this context, the industry was ripe for intervention. The games for girls movement was an effort by game developers and game companies like Her Interactive, Girl Games, Girltech, and of course Laurel’s own Purple Moon to attract girls and young women as players by producing games. These companies presented a kind of “entrepreneurial feminism” in which women founders sought to intervene in a male-dominated industry that catered to boys and young men (King and Douai 2014, 4). As co-founder and VP of design at Purple Moon, Brenda Laurel was at the forefront of this movement.

Purple Moon emerged from a multi-year project at Interval examining girls’ attitudes toward and interest in games and play: “We did hundreds—maybe thousands—of interviews with seven- to twelve-year-olds, the group we wanted to target with our products. We watched play differences between boys and girls. We asked kids how they liked to play; we gave them props and mocked-up products to fool around with” (Laurel, quoted in Beato 1997b, n.p.). Beyond this, the team delved into existing research on related topics and also spoke to working experts ranging from toy store owners to scout troop leaders (Beato 1997a). Inspired by the solutions suggested by the years of research, Purple Moon launched in 1996.

Startups like Purple Moon, Her Interactive, and Girl Games, Inc. helped pioneer efforts to target girls in the mid-1990s, but major media and toy companies also entered the market. Sparked in part by the runaway success of Mattel’s Barbie Fashion Designer (1996), which sold over 500,000 copies in two months and became a bestselling CD-ROM title, the games for girls movement saw a roughly tenfold increase in the production of game and software titles targeting girls from 1996 to 1997. Well-established toy and media companies like Mattel Media, Hasbro Interactive, Sega, DreamWorks Interactive, and Phillips Media, among others, began producing titles in this area. While in 1996, Barbie Fashion Designer was the standout of less than two dozen games for young girls, in 1997, some 200 games targeting an audience of girls were released by a diverse mix of established and start-up companies (Beato 1997a).

Among that flurry of games for girls released in 1997 was Rockett’s New School, the first game from Purple Moon and the first game in the company’s Rockett Movado series. In Rockett’s New School, the titular Rockett starts eighth grade at a new school; the player leads Rockett through various social situations with friendly and hostile peers and teachers and other school staff. Laurel served as designer on Rockett’s New School and the game reflects both the conclusions of Laurel’s research and the general focus of Purple Moon’s games. The company’s titles, including the Rockett Movado series and the Secret Paths series, rely on interactive decision-making as a core mechanic and encourage values like friendship and self-awareness. With these games, the company sought an audience of preteen girls.

Under Laurel’s direction, Purple Moon’s design ethos was one highly informed by detailed research into prospective players’ interests, concerns, and habits. In a 1997 interview, Laurel said that her research at Interval was contingent on the agreement that she would defer to what the research found: “I agreed that whatever solution the research suggested, I’d go along with. Even if it meant shipping products in pink boxes” (Beato 1997b). But because of this reliance on research, the games ultimately did not ship in pink boxes. Rather, the games formed what journalist Patricia Ramirez has called a “‘purple games’ segment of the [games for girls] movement,” one focused less on pink-washed assumptions about what girls should want and more on detailed research into what girls really did want (Hernandez 2012, n.p.).

In a 2014 interview, Rebecca Hains, an expert on girls’ media and author of The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years, summarizes the issue with pink-washing:

By “pink-washing,” I’m specifically referring to the instances where marketers or toy makers create a product that is pink for no reason other than to make it as girly as possible. After all, there’s nothing wrong with pink—it’s a perfectly nice color—but there IS something wrong when it’s a) promoting sex role stereotypes and b) basically the only color found in little girls’ worlds. They deserve a full rainbow of colors. (Siegel 2014, n.p.)

As Hernandez suggests, the games produced under Brenda Laurel at Purple Moon were not pink-washed; they were something else. In this, they contrasted sharply with other games on the market at the time. For example, Barbie Fashion Designer is a clever piece of software that enables players to design, print, and construct clothes for their dolls; however, it and other Barbie games rely on an established and dominant brand with its own fraught gender history (Banks 2003; Rogers 1999), and a huge percent of the paltry number of games intended for young girls were either tied to established girls’ toy brands or were clumsy efforts by adult male developers to make something, anything, for girls. By contrast, Purple Moon’s games did not represent adult imaginings of what girls might want or simply put a game originally meant for boys in pink packaging. The games instead addressed girls’ real needs and desires through a meticulous research and design process.

Purple Moon’s distinct aesthetic reflects a design process that went beyond pointless feminization, seeking instead to craft games that would resonate with girls. Purple Moon’s games were feminine, but they were carefully, thoughtfully so. The storybook art style of the Secret Paths games, the social maneuverings of Rockett and her friends, and even the online community available on the Purple Moon website can all be seen as feminine, particularly when contrasted to other games produced at the time. But these games are gendered media based not on stereotyped prescription but rather on researched fulfillment. The games presented themes and topics of demonstrable interest to the target demographic; even before launch, the company was referring to the games as part of a new genre: “friendship adventures for girls” (Beato 1997a, n.p.).

This same research-driven approach made the company sometimes controversial. Since the research showed that girls were interested in topics like friendship, journaling, and their social lives, Purple Moon focused on those topics; however, since those interests often aligned with gendered stereotypes of girls’ interests, the games were ripe for criticism. At points, Laurel and her company faced pushback on multiple fronts. Game reviewers, for example, often panned the games, and feminist critics attacked the gender essentialism inherent to the idea of games for girls (Laurel interview by Kocurek 2015). However, they hit the mark with the intended audience and sold well (exact numbers aren’t available). Girls enjoyed the games even as adults debated their merits.

The games’ success with girls demonstrates the merits of research as a basis for reaching new player demographics. Adult misgivings are also instructive as they highlight how difficult producing meaningful media can be within political, economic, and social strictures. The choice to listen to adults over children might have made the games more palatable to critics, but it would have made them less enjoyable and less important for girls. Trusting research to inform design ultimately means trusting the players. While for the game industry at large girls had been at best incidental consumers, for Purple Moon, girls and their needs and desires were the entire point of making games at all.

Brenda Laurel by design

Brenda Laurel becomes the designer she is through a series of choices and opportunities that shaped her approach to and understanding of computers, games, and design. A long-standing interest in theater served as a foundation for much of Laurel’s earlier work, but her entry into the computer games industry—as a means to sustain herself during graduate school—altered her path. From her work developing computer games, Laurel came to think about the computer as a medium for dramatic storytelling and turned her attention to this potential.

Her knowledge of and approach to theater shaped her understanding of human–computer interaction, and her unique insights positioned her well for a career in Silicon Valley. There, she worked at companies including Atari, where she was able to join the company’s research lab. At the lab, she began to think of herself as a researcher as she continued her work on interactive storytelling, much of which informed her dissertation and later her book Computers as Theatre. Laurel left Atari and worked as a consultant and at a number of game companies in a variety of production and management roles before landing at Interval Research Corporation. At Interval, Laurel tested her ideas about interface design and storytelling through experiments in virtual reality and also worked on a massive, years-long study of girls and computer games. The threads of these experience—her training in theater, her unique approach to HCI, her experience as a researcher, and her deep interest in the storytelling potential of interactive media—are fundamental to who Laurel is as a designer and go a long way toward explaining her approach to game design.

Theoretically theatrical

A reliance on her skills as a researcher and her willingness to trust her research—to follow the direction the research suggests even if it meant “shipping products in pink boxes”—propelled Laurel to follow innovative approaches in game design. Laurel helped pioneer the games for girls movement by seeking to diversify the gaming audience, and she also forwarded the notion of usi...