![]()

Part One

Constructing Multiple Identities

![]()

1

Gauguin’s Alter Egos: Writing the Other and the Self

Linda Goddard

University of St. Andrews

Responses to Gauguin’s art have been inseparable from reactions to his controversial life and self-curated persona. As Abigail Solomon-Godeau described in her classic essay of 1989, “Going Native,” Gauguin was a “persuasive purveyor of his own mythology,” through self-portraiture, photographs that he liked to circulate among his disciples and statements in which he cast himself as a misunderstood genius.1 This role-playing fed into the triumphalist presentation of the artist as the “founding father of primitivism” in biographies and exhibitions. Gauguin colluded fully, she argued, in the potent art-historical myth whose goal was to chart his “assumption of the role of savage,” a cynical masquerade that occluded the realities of racial and gendered power structures in the colonial context.2

Subsequent scholars, notably Stephen F. Eisenman, Lee Wallace and Hal Foster, have drawn attention to the fragility and insecurity of Gauguin’s white masculinity. Despite their internal differences, collectively these readings have led to a focus in the Gauguin literature on the mutability and hybridity of the self, in its psychic, social, and sexual dimensions, premised on an understanding of the colonial encounter as both reciprocal and ambivalent.3 My claim is that a study of Gauguin’s writings that gives due weight to their literary strategies has much to add to these newer perspectives on his colonial identity. The perception of racial and sexual difference, mixed with a desire to transcend it, which structured his primitivist outlook, is also pertinent to Gauguin’s sense of the different characteristics of visual and verbal expression, and a serious account of his writings needs to acknowledge their conscious primitivism.4 Gauguin aligned the visual artist with the “savage” and the writer with the “civilized,” contrasting the intuitive sensibility of the former with the rote learning of the latter, but was ambivalently suspended between the two.5 As is well known, he sought to protect Polynesian society from “civilization,” but remained implicated in the imperialist culture that he denounced. Equally paradoxically, he defended artists against verbal intervention, but was a prolific writer himself, producing five extant manuscripts, published essays and correspondence, and editing two newspapers.6 In its uneasy confrontation of roles that he sought to distinguish, his hybrid identity as an artist-writer complements his liminal status as a critical primitivist or reluctant colonizer, on the margins of both the indigenous and settler communities.7

Gauguin’s writings also foreground the constructedness of identity in the sense that their fragmentary and repetitive structure prevents the establishment of a unified authorial voice. Civilized and savage were terms that Gauguin set in opposition, in line with the rhetoric of imperialism, but also combined, inverted and moved between. His statements draw attention more often to the divisions in his persona than to any stable sense of self. They trade in stereotypes, but allow for relativity and fluctuation: “To them [the Tahitians] I was a ‘savage,’” he wrote in Noa Noa; in a letter to a French acquaintance he called himself a “civilized savage”; to Emile Schuffenecker a “savage from Peru”; and in Avant et après a “coarse sailor” but also a “descendant of a Borgia of Aragon.”8 In this essay, I will show how his volatile self-positioning is paralleled by the way in which he constructed his writings. In a process that has been little studied, he created multiple authorial positions, both by borrowing the words of others, and by writing under different guises himself. The principle of assemblage that governs the narrative content of his manuscripts extends to their physical format, resulting in a striking scrapbook aesthetic that is lost in the printed editions, and rarely taken into account when his writings are consulted for their biographical interest, or to assist in the iconographical interpretation of his art works.

“Scattered notes, without sequence like dreams, like life all made up of fragments.” Gauguin characterized three of his manuscripts this way, highlighting their disjointed structure.9 In two cases he added “And because others have collaborated in it, the love of beautiful things seen in your neighbor’s house,” thus also drawing attention to their multiple sources.10 If we interpret his writings as an integral component of his creative practice, rather than a commentary upon it, then the qualities of reiteration and appropriation that are typical of his work, and which have excited scholarly interest in the context of recent exhibitions of his prints, come into sharper focus. For not only is Gauguin’s fragmentary manner of textual composition equivalent to the procedure that he adopted for his painting, sculpture, and printmaking, but the manuscripts vividly materialize the process of appropriation, so that it becomes much more palpable and obvious in this format. If, arguably, Gauguin’s habitual borrowing is concealed in his painting (such as his sampling of poses from the photographs that he owned of the Borobudur Temple reliefs of the Life of Buddha), in the cut-and-paste composition of his illustrated manuscripts it is immediately apparent.

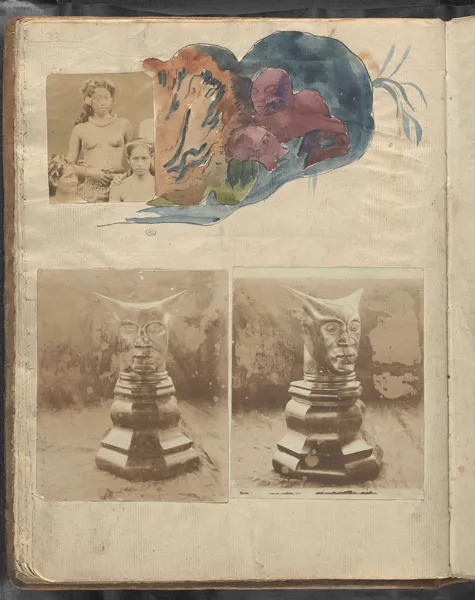

A couple of examples will illustrate this point. In the manuscript of Noa Noa held in the Musée du Louvre, which is Gauguin’s copy of the text he drafted in 1893 then revised in collaboration with the poet Charles Morice, he incorporated several sequences of images that confront originals with reproductions.11 In one layout combining photographs, original watercolors, and a pasted-in fragment of a woodcut, the possibility of doubling suggested by the inherently reproductive media of print and photography is heightened by a series of pairings (Figure 1.1). In the lower register of the left-hand page, two almost identical photographs capture Gauguin’s sculpture Head with Horns from alternative angles, in images of slightly different scales. Two Polynesian women (in one case, the prominent figure in a group), each photographed from the waist up and with their naked torsos angled a little towards each other, echo each other across the double-page spread, the similarity in pose and photographic format suggesting that they are intended to be emblematic of Polynesian femininity: different and yet the same.

Figure 1.1 Paul Gauguin, page from Noa Noa with photographs of a Tahitian family and two idols, 1895–9, watercolor, brown ink and photographs, 12⅜ × 18⅛ in. (31.5 × 46 cm).

At the top of the left-hand page, Gauguin has painted directly on the page around the group photograph, as though the women were imagining—or perhaps metamorphosing into—the ghostly figures that emerge from an amorphous mass of colored shapes that encroaches upon, or emanates from, them. Such a provocative juxtaposition of the mechanical and the artist’s hand may be intended to privilege the latter, implying that it is he alone, with his imaginative, semi-abstract inventions, who has the power to extract the spiritual core of Tahiti from the tourist vision conveyed in photographs. The intimate physical overlap between painting and photograph, however, also calls that hierarchy into question. Gauguin’s activation of the creative tension between media recalls the assortment of sketches, copies, reproductions, and photographs found in the albums or keepsakes of nineteenth-century amateur women artists, or the sketchbooks of Edgar Degas, whose own experimental printmaking challenged the distinction between creating and reproducing.12 Addressing the physical format of Gauguin’s manuscripts therefore allows us to place them in a visual and material cultural tradition that befits his description of Noa Noa, in the preface of the Louvre version, as a “book to be seen as well as read.”13

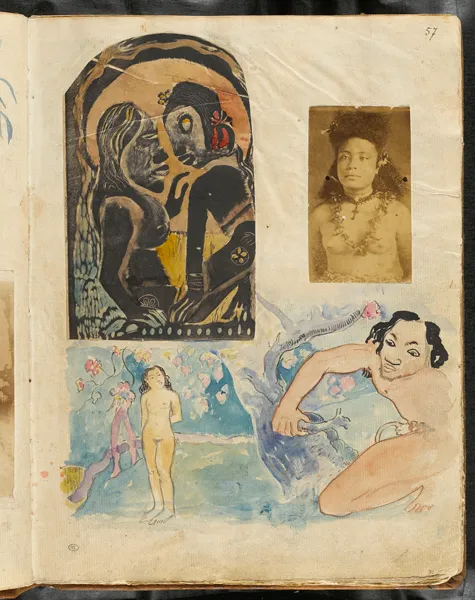

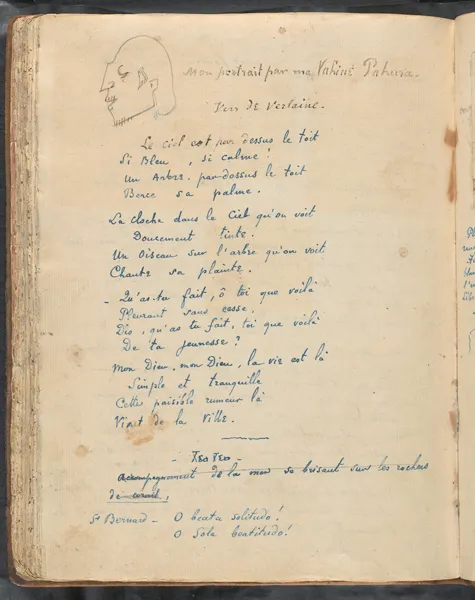

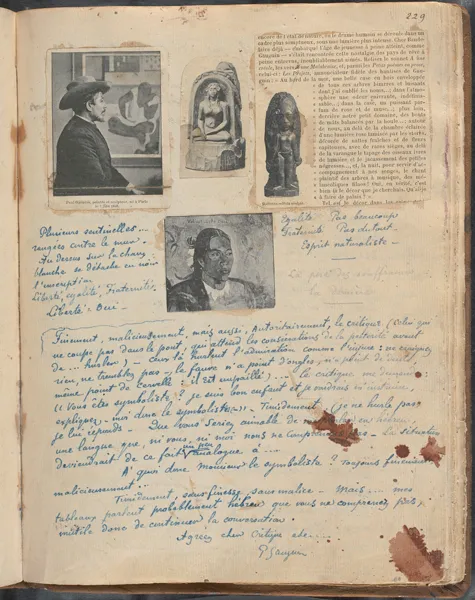

Different voices, as well as media, come into play on the pages of Diverses choses, whose title (Various Things) reflects its compilation of words and images from many sources (Figure 1.2).14 In one double-page spread, Gauguin writes as himself, in the guise of a scathing imaginary letter to a critic (which concludes, at the bottom of the right-hand page, “agréez cher critique, etc …. Paul Gauguin”), copies verses from Paul Verlaine, pastes in a critic’s review of his work, and imagines himself as viewed through the eyes of another in the self-portrait sketch at the top of the left-hand page, which is captioned “my portrait by my vahine Pahura” (mon portrait par ma vahine Pahura). Adding to the visual interest already supplied by the combination of writing, sketch and reproduced photographs of Gauguin and his work is the arrangement of Gauguin’s handwriting in a variety of configurations dictated by the conventional formats of diverse literary genres: poem, letter, caption, newsprint and, elsewhere on the page, proverb or aphorism.15

Figure 1.2 Paul Gauguin, autograph annotations and caricature self-portrait, from the Noa Noa album, 1895–9, pen with blue and brown ink, 12⅜ × 18⅛ in. (31.5 × 46 cm).

Citation is central to Gauguin’s writing. On the opening page of his first manuscript, dated 1893, which he dedicated to his daughter, Aline, four names appear in succession, initiating the chorus of voices that continues in the remainder of the volume: Aline, in the handwritten dedication at the top of the page; Gauguin, Charles Morice and Jean Dolent, as the subject, dedicatee, and author, respectively, of a collaged newspaper article—the multivocality emphasized by the combination of handwriting and newsprint (Figure 1.3).16 The book then continues with another voice, that of Edgar Allan Poe, in a series of excerpts from his Marginalia (1844–9) that reappear in Diverses choses (so that we have multiplicity and reiteration).17 The extracts from Poe, which are, after all, his Marginalia, or gathered reflections, end with quotations from other famous epigrammatists, Nicolas Chamfort and Epicurus. Poe’s borrowed thoughts are followed by the words of Richard Wagner, likewise cited on other occasions by Gaug...