![]()

Suppose you are walking along a road and you encounter a large, snarling dog? Your natural reaction might well be to drop your belongings and climb the nearest tree to get out of the dog’s reach. Suppose you do so—and shortly afterward, from your perch on the tree, you watch as another person, in response to the same snarling dog, simply claps her hands, whereupon the dog wags its tail and leaps about playfully?

You’ve just experienced the two kinds of cognitive processes that work in the human brain—and which inform many of the chapters in this book. Screenwriters (and filmmakers) who are aware of their audience’s propensity to arrive at conclusions based on partial information can exploit it to great effect, especially in manipulating and foiling audience expectation.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up

Perceptual processes—those involving the five senses—rely on external physical stimulation and are termed bottom-up processes. The incoming sensory information arrives through your sense organs as raw stimuli—wavelengths of light, shapes, vibrations in the air—and are passed into the neurons of your brain. Stimuli start at the “bottom”—the outside world—and go up into your brain.

Gradually our experiences are assembled as memories, with emotions and relationships between various stimuli established in the brain’s “experience structures.” While there is no single brain location that stores each new experience, there are some key players in structures beneath the cortex—or surface of the brain—subcortical areas with exotic names like thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampi. All that real-world energy becomes patterns of electrical impulses and is eventually organized into concepts and categories. This process occurs throughout our lives, but is especially active in our early years, when the brain is exposed to a virtually constant stream of new information. From repeated experience with real-world stimuli, we begin to know our world, other people, and ourselves. This experience-based processing enables what is called top-down information flow and evolves into our own personalized understanding of an object or event. The external world enters our brains through our spectacular sensory systems and is perceived only after our brain compares our stored information with new information flowing in.

Thus our response to the snarling dog was not based solely on the sight of an animal with bared teeth; it was a consequence of previous information stored in the brain’s experience structures, information about what snarling dogs look like, cross-referenced with information about what snarling dogs can do to you with their teeth. Our processing starts at the top—our brains—and determines our behavior in the world—down.

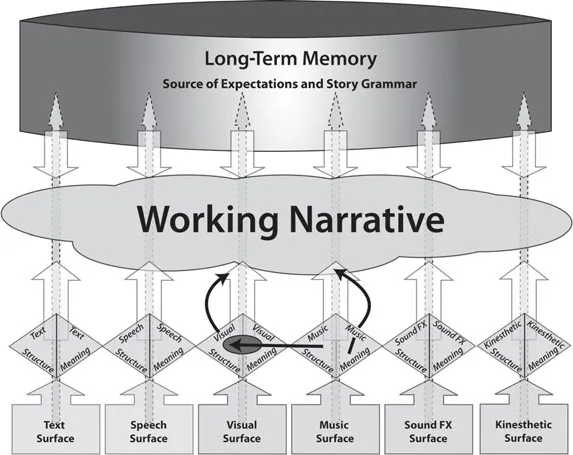

A. J. Cohen, a psychologist from the University of Prince Edward Island in Canada, has depicted the intersection of top-down and bottom-up as forming the working narrative in a reader’s or a viewer’s brain. From the bottom of the model, she presents six sensory sources of incoming, real-world energy, termed surface information—this is the snarling dog part of the scenario above. Next, sight and sound—now electrochemical brain activity—begin to connect with our search for meaning. In the model, labeled long-term memory, all our life’s experiences, expectations, and understanding feed down, forming a structure to associate what we know with what is incoming: this is where we climb up the tree in our flight from the aforementioned snarling dog. Cohen’s CAM-WN illustrates the audience members’ brains as they process your movie from bottom-up sights and sounds associating with their top-down expectations, as the cloud in the middle, an evolving comprehension of your story, their working narrative.

The woman who appeared after you were in a tree, though, received the same visual information, but responded differently. Why? In this case, her brain contained a piece of information yours lacked—this was her dog. She knew from prior experience that her own dog snarled when it wanted to play.

Actually, she was operating under a different schema than you.

I Say Schema, You Say Schemata

Although our brains are very complex, they are easily overwhelmed by all the information that comes through our senses. As a consequence, the brain works by way of some significant shortcuts. These shortcuts can be manipulated by skillful storytellers in important ways relating to maintaining audience attention.

One such shortcut is object recognition. For example, the first time you encounter an array of stimuli through your eyes as a pattern of orange and black colors with a distinct shape, these details will be noted and stored in your brain’s memory in detail (bottom-up processing). However, once these details are identified as a butterfly, subsequent encounters with these stimuli will be instantly recognizable as a butterfly (top-down processing) without a detailed analysis. The recognition is virtually instantaneous—a great advantage if your life depends on quickly recognizing a dangerous animal or a possible food source. In addition, your experience encountering a butterfly—warm, sunny day, clouds puffy in blue skies, your caregiver exclaiming “How beautiful! A butterfly!”—shape your object recognition into your attitude and potential behavioral response for the next time you encounter that object. Consider your response if your first encounter with an object is cold, wet, and someone is screeching, “Spider! Squash it!”

So you can see our brain’s object recognition is an integral automatic process that intimately combines bottom-up and top-down information flows. In fact, we really don’t have any control over our ability to recognize things or people—it just happens.

Another very important cognitive shortcut is called a schema (or schemata—the terms are interchangeable): an organized set of related concepts or objects, usually within a specific scene—the word scene in this case having a scientific—as opposed to cinematic—meaning (a figure in the context of a background). For example, if you enter a room and encounter a pile of gift-wrapped boxes, ribbons, place settings consisting of paper plates and plastic forks, and a cake with some candles on it, your brain will likely identify the schema birthday party.

But our top-down processing has another important aspect beyond the simple recognition of patterns and organized shortcuts: it can affect our behavior. In fact, much of the information we receive through our senses is incomplete or ambiguous, and the brain, as a consequence, is quite creative, actively filling in blanks with assumptions, based on experience (this is known in psychology as the theory of constructivism).

The snarling dog you encountered earlier was an object within a scene—strange dog, bared teeth, unattended—and your response was to flee. The woman who played with the dog, though, had a very different response, which informed her behavior: “my dog.” Your incomplete information led you to a conclusion that proved to be untrue, because the snarling dog was not dangerous. When new information arises that contradicts a schema, psychologists term this a violation of one’s schema.

How can the audience’s propensity to construct schemas be exploited by filmmakers? Essentially, any time you experience a “surprise twist” in a movie, chances are the filmmaker gave you clues by which you constructed a schema, then violated the schema by introducing information that was withheld from you.

Examples from cinema are innumerable.

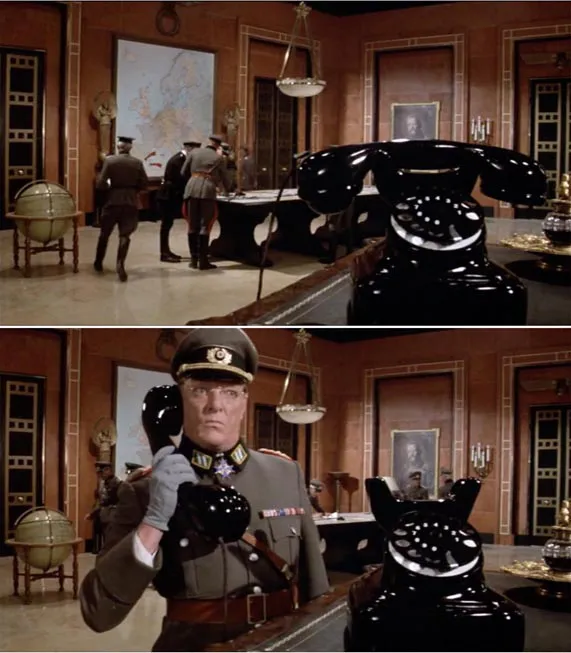

Several of the sight gags in the 1984 film Top Secret rely on offering the viewer incomplete information, resulting in the construction of top-down connections in the viewers’ mind that, with new information, prove to be false (see Figure 1.4).

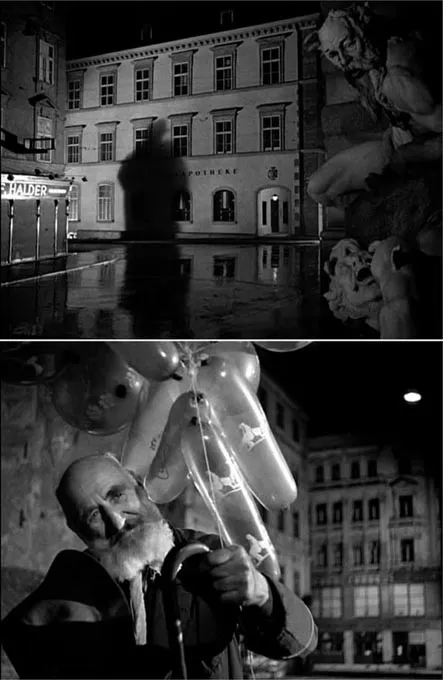

Another example of such a top-down construction can be seen in Figure 1.5, from the 1949 film The Third Man. The clues suggest menace; the reality proves to be very different.

Frame versus Scene

Schemas, organized sets of knowledge, are set within frames—a boundary that allows viewers to see the ominous shadow in Figure 1.5 within the frame of a dark, lonely street. Frames, then, are mental limits, setting expectations based on viewers’ experiences (their schemas). When The Third Man changes camera perspective revealing the source of the shadow, viewers have had their expectations violated. Such violations of the frame create tension that helps to hold the viewer’s attention—which is the primary job of any storyteller.

Of central importance to screenwriters and filmmakers is the second type of knowledge within schemas, known by psychologists, appropriately enough, as a schema script—the actions we have come to associate with a particular schema. For example, in our birthday party schema, the frame could be a family home or a gathering at a specific place. The schema script would include actions such as arriving guests, lighting candles, singing Happy Birthday, and opening gifts. However, if after everyone sings Happy Birthday, a gunman pops out of the cake and guns people down, we have a violation of script for our schema: An unexpected action has gr...