![]()

1

Beyond the Curtain: The ‘True Nature’ of Microphones and Loudspeakers

An empty stage: Listening according to the Konzertreform

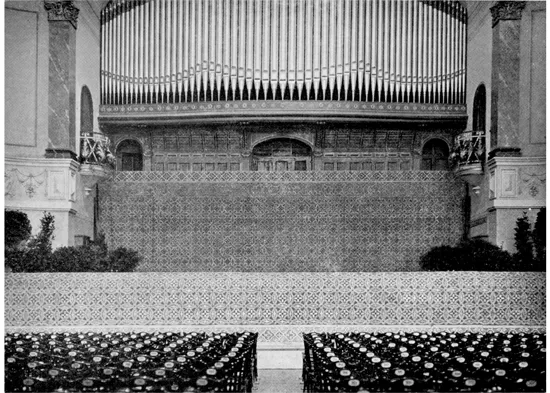

The audience sits quietly in the concert hall. The lights are dimmed. The music starts, but the performers are not visible. The musical performance reaches the audience only through sound, devoid of visual cues. Due to the invisibility of this musical performance – forcing the audience to focus on sound rather than sight – the poignancy of the performance becomes augmented (Wolfrum 1915, 5, 10). The picture at the beginning of this chapter (Figure 1.1) was taken in a concert hall in Heidelberg (Germany) in 1903 and depicts the set-up in the concert hall as used for this kind of invisible musical performance. The orchestra and choir are hidden behind panels and curtains, with the aim of eliminating anything that might distract the eye and the ear of the audience (von Seydlitz 1903, 97). All distracting movements of the performers, for example the ‘prima donna coquetry by certain conductors’ (Wolfrum 1915, 5), take place behind a curtain, and only that part of the audience which needed to ‘learn’ from the performance, such as music students, was permitted to sit on the other side of this curtain, able to view the conductor and musicians.

Figure 1.1 Konzertreform: to hide the choir and the orchestra panels were installed in the concert hall ‘Stadthalle’ in 1903 Heidelberg, Germany (Schuster 1903/04).

These conceptualizations of a concert practice which would focus as much as possible on only the audible elements of music were formulated and put into practice by several musicians at the beginning of the twentieth century, mainly in Germany, in the context of what contemporary theoreticians termed Konzertreform. Whereas the core idea of this movement – presenting music with the performers hidden behind curtains – did not persist, many of the postulations of this Konzertreform formed part of a drastically changing concert practice, from the end of the nineteenth through the beginning of the twentieth century. By the end of the nineteenth century, the audience was expected to be as silent as possible during the musical performance and not to talk out loud anymore, hum with the music or beat the rhythm with hands, head, or feet (Johnson 1996, 232–233). Additionally, applause during symphonies was abandoned and only allowed to happen at the end of a piece of music, instead of after each movement or even during the music itself (Ross 2010). Apparently, all of this audience behaviour was previously considered normal, or at least possible, during concerts, otherwise the formulation of such rules would have been unnecessary. Many other common features of classical music concerts nowadays were introduced in relation to the Konzertreform. For example, a large foyer between the entrance and the concert hall, creating a division between the social activities of the audience and the activity of listening, was deemed necessary (Marsop 1903, 433). In this way, the social interaction which used to take place within the concert hall during the performance could now take place outside. A sound signalling the start of the performance was initiated, giving the audience the chance to become completely silent (von Seydlitz 1903, 100). Concerts should take place in darkened concert halls, so that audience members would not be visually distracted. The aim of all these sanctions was to ‘give the sense of hearing full priority for the audience member, through putting to rest the eye, his biggest enemy’1 (Holzamer-Heppenheim 1902, 1293).

Most of the aforementioned claims have become enduring conventions for classical music concerts. The extreme practice of hiding the musicians behind curtains during the concert as described at the beginning of this chapter should be regarded as a by-product of a larger aim or programme to achieve more focus on the purely sonic aspect of the music. Many of the proclaimers of the Konzertreform were inspired by the sonic phenomenon of the famous invisible orchestra in Richard Wagner’s theatre in Bayreuth (Marsop 1903, 428–429). The curtains hiding the musicians had not only a visual aspect but served an acoustical purpose as well. Making use of the good acoustic conditions in the Bayreuth theatre (nowadays called Richard Wagner Festspielhaus) as well as the indirect sound of the orchestra, due to the orchestra pit being recessed, the sound was perceived as ‘cleaned’ by this so-called ‘sound-wall’ (von Seydlitz 1903, 99). Sound waves could not reach the audience directly because of the curtain, which transformed the sound of the orchestra into something mellower. As a result, the hidden musical instruments could be located easily neither by the ears nor by the eyes of the audience. The aim was to avoid focusing in a specific direction, and thus to achieve a listening situation in which the audience would be completely overwhelmed by sound alone, absent of any material source recognizable as the cause of this sound. Considering that up to that time church organists were one of the few instrumentalists hidden from the audience, placed in the back of the church on a balcony, it might come as no surprise that this concert practice – as it was developed during the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century – has been called a religious ritual, eliciting remarks that the listening attitude might be compared with silent praying (Tröndle 2009, 47). The only important feature of a music performance was the contact between the listener and the sound of the music; all other elements were considered to be a distraction. The possibility of music performances existing in the form of sound alone arose, and for many audience members, such as the advocates of the Konzertreform, this situation was preferable to that of a conventional concert.

A concert at home: The invention of sound reproduction technologies

Whereas the ideas of the Konzertreform did not endure in actual practice, listening to music without any distraction of, for example, musicians’ movements or audience members’ noises became possible in another way. In listening to music on a record or on radio, listening conditions similar to the ones set into practice by the Konzertreform became mainstream. In fact, the ideas developed around the phenomenon of the classical music concert, resulting in the sound of a musical performance being the most or even the only important element of music, were essential to the development of a music performance culture mediated through radios, gramophones and CD players at home. These devices are all commonly called sound reproduction technologies due to their primary function. This technology was developed in a cultural context calling for the emancipation of sound, which was understood as sound being recognized as the only element necessary for a complete perception of music, instead of the integral musical performance, all visual aspects included. The idea that nothing fundamental was missing when visual aspects of musical performance are excluded was therefore a necessary context for the successful rise of music recordings as replete musical experience during the last century. Listening to a musical performance on the radio can therefore feasibly be considered as a successor of listening to a concert in a concert hall where the performers are hidden (Schwab 1971, 186).

It is often averred that inventions like the phonograph or the radio force the audience to listen to music without viewing its source and effected ‘the physical separation of listening from performing’ (Chanan 1995, 7). I would argue, however, that the ideals of the Konzertreform clearly reveal that this new mode of perceiving music was not necessarily preceded by the invention of new technology, but can be seen as an aesthetic development which took place during the nineteenth century, concurrent with the invention of sound reproduction technologies such as telephones, phonographs and radios. Although these kinds of devices did not instigate a new way of perceiving music, they did make it much easier to listen only to the sound of music instead of perceiving the whole performance, including its visual elements. A singular sound can only exist at a specific time and at a specific place, since it is formed by waves of pressure that are by definition in constant motion. Before the invention of sound reproduction technology, music never took place without the presence of musicians and their musical instruments, or – in the case of music automata – at the very least the presence of the musical instruments. Listening to music was directly connected to this presence of musical instruments. The Konzertreform attempted to disconnect the audience as much as possible from this presence by hiding the instruments behind a curtain, but it was through sound reproduction technology that, for the first time, they no longer needed to be present in the same space or at the same time as the listener. What all sound reproduction devices have in common is that they release sound from its direct connection to a certain time and space. This is done in two ways: either by storing sound (taking it out of its time) and by transporting or amplifying sound (taking sound out of its place). The sound waves – air pressure waves2 perceived by the human reception system as sound – are transformed into a form of energy which dissipates less than air pressure waves. As I make clear in the next paragraphs, microphones and loudspeakers are crucial to the transformation of sound waves, since they are transducers of air pressure waves to this more enduring form of energy: an electrical signal.

Storage of air pressure waves

In order to store air pressure waves, their time-related form consisting of pressure differences needs to be translated into another, more sustainable material, such as wax, vinyl, magnetic tape or any form of contemporary digital storage, for example. The sound is now coded not through pressure differences in air but through differences in the depth or deviation of a groove, differences of magnetic power or binary numbers. This information is transformed back to air pressure waves either by using a mechanical, such as early phonograph needles, or an electric conversion system, used by nearly all sound reproduction devices nowadays, which brings into vibration a diaphragm.

Jonathan Sterne* did extensive research on sound reproduction technologies and their cultural origins. In his book The Audible Past he proposes the idea of the tympanic mechanism, informed by the human eardrum, as a mechanism for transducing vibrations (see Chapter 3 for a more in-depth discussion of the tympanic function). This tympanic mechanism is (re)produced in the sound reproduction technology found in microphones and loudspeakers, their diaphragms being comparable with the membrane of the ear.3 As Sterne describes clearly: ‘every apparatus of sound reproduction has a tympanic function at precisely the point where it turns sound into something else – usually electric current – and when it turns something else into sound. Microphones and speakers are transducers; they turn sound into other things, and they turn other things into sound’ (Sterne 2003, 34). Devices used for the transformation of air pressure waves to something else and vice versa is therefore how I define microphones and loudspeakers. Although there have been many new inventions within sound reproduction technology since the end of the nineteenth century, such as electric amplification, digital recording and processing, ‘it is still impossible to think of a configuration of technologies that makes sense as sound reproduction without either microphones or speakers’ (Sterne 2003, 34–35). Whereas there are many different technologies to store sound, like gramophone records, cassette tapes, CDs and MP3s, the connection between air pressure waves and the electrical signal is nearly always performed by microphones and loudspeakers.4

Transportation of air pressure waves

What distinguishes the tympanic principle from other ways of producing sound is that – ideally – all kinds of sounds can be produced by the same membrane, hence also the term sound reproduction technology. The idea of using a membrane for converting sound waves into ‘something else’ can, for example, also be demonstrated in the so-called tin can telephones. Two tin cans, paper cups, or similar objects are attached to each end of a wire. Speaking softly in one of the cans causes the bottom of the can to vibrate. This bottom functions as a membrane able to vibrate in response to various air pressure waves. These vibrations are transported along the wire to the bottom of the other tin can. A person at the other side of the wire will therefore be able to hear the sound, as transported from one tin can bottom to the other by the wire. This simple ‘telephone’ reveals how crucial the tympanic mechanism as described by Sterne is for sound reproduction technology. To reproduce a sound, there is no longer need for a mechanical reconstruction of the objects that produced that sound, as for example in the case of musical automata. Therefore, instead of creating a different sound-producing device for every sound, the membrane – more specifically called diaphragm – was incorporated as a general solution for the conversion of sound into mechanical vibrations or an electrical signal and back: a metaphorical tin can is used at both ends of the wire, functioning once as microphone and once as loudspeaker. The tin can telephone is nowadays replaced by a telephone which uses electricity to transport the transduced sound waves. An electrical signal is transported by a wire, with a small microphone and loudspeaker at either end to make transductions between air pressure waves and electricity.

Amplification of air pressure waves

Air pressure waves lose energy when they move through the air. Already in ancient history solutions were sought for this problem. Sound is normally dispersed in all directions. By focusing sound waves with a horn, the sound waves are all forced to move into one direction. As a result, audiences will hear the sound louder. Horns are therefore used for sound amplification (although physically speaking they are only focusing and not amplifying sound waves). In ancient Greek and Roman theatre, masks were introduced which not only helped the spectators to distinguish the characters but also served as amplifiers for the actor’s voice. The opened mouth of the mask was shaped in the form of a horn (Floch 1943, 53). The horn was used to amplify the human voice, so more spectators could clearly hear what the actor was saying. This horn could therefore be seen as fulfilling the same function as microphones, amplifiers and loudspeakers nowadays, to amplify the actors’ and/or singers’ voices on stage.

Till the end of the nineteenth century, ‘amplification’ (in fact focusing) of sound waves was mostly achieved using horns, often much bigger than those integrated into the Greek masks. A late example is the large megaphone (1878) developed by Thomas Edison* (Figure 1.2). This megaphone is nothing more than an enormous enlargement of the human ears and mouth, similar to the enlargement of the mouth by the Greek mask. Two large metal or wooden horns around 180 centimetres in length were used as ear enlargements, and a third horn was placed in front of the mouth. In this way Edison was able to communicate over distances of more than three kilometres (Dyer 2004, 89–90). Edison claimed that he was even able to hear ‘a cow biting off and chewing grass’ (Baldwin 2001, 91). What these horns evidence is that for a significant amplification of sound, whether sending or receiving and without the use of electricity, an enormous object is needed. After the introduction of electricity into the process of sound amplification, the amplifier horn became obsolete. Since Edison invented his megaphone at the same time as the telephone (invented in 1876), his megaphone was, in the end, not used for communication over long distances. This was done much more effectivel...