![]()

It is inadequate to affirm that a people was dispossessed, oppressed or slaughtered, denied its rights and its political existence, without at the same time doing what [Frantz] Fanon did during the Algerian war, affiliating those horrors with the similar afflictions of other people. This does not at all mean a loss in historical specificity, but rather it guards against the possibility that a lesson learned about oppression in one place will be forgotten or violated in another time and place.

—EDWARD SAID, REPRESENTATIONS OF THE INTELLECTUAL, 25

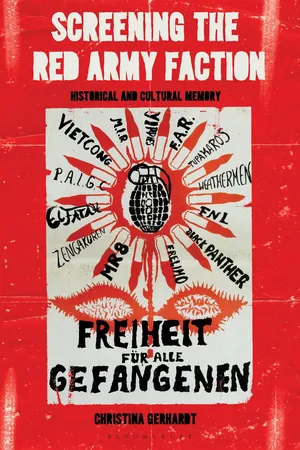

Around 1968 self-liberation and self-determination struggles rose up the globe over, seeking to challenge hegemonic structures in society, at the workplace, at universities, and at home. While these movements sought to address conditions domestically, they also expressed solidarity internationally. For example, as many of the speeches, writings, leaflets, banners at demonstrations, and films of the era evidence, people around the world protested the US war on Vietnam. Often citing and encapsulated by Che Guevara’s “Create Two, Three, Many Vietnams,” the movements organized in solidarity with the anticolonial and anti-imperialist struggles of the Viê.t Cô.ng and drew inspiration from Che Guevara’s role in the 1959 Cuban Revolution, which overthrew US-backed Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.

At the same time, each late 1960s movement emerged from and responded to the distinct political concerns posed by its unique national history. In West Germany, the fascist legacy, the ruins of the Second World War, and the Cold War shaped the ensuing social movements. The Second World War ended on May 8, 1945, in Europe, and West Germany was established on May 23, 1949. Seeking to work through the past,1 the younger generation inquired into their parents’ active or passive participation in the fascist era. They criticized the silence about the National Socialist (Nazi, Nationalsozialistisch) period and the lack—especially in contrast with East Germany—of denazification of West Germany.2 In the Allied occupied zones, denazification programs were scaled down and handed over to the regional states in August 1948, with the order to finish prosecutions by the end of 1949, at which point prosecution rates fell dramatically.3 As William Graf points out, “Almost all the representatives of big business labeled as war criminals by the American Kilgore Commission in 1945 were back in their former positions by 1948; and of roughly 53,000 civil servants dismissed on account of their Nazi pasts in 1945, only about 1000 remained permanently excluded, while the judiciary was almost 100% restored as early as 1946.”4 According to Jeremy Varon, a few decades later, “as of 1965, fully 60 percent of West German military officers had fought for the Nazis, and at least two-thirds of judges had served the Third Reich.”5

In West Germany, former Nazis thus continued to hold high-ranking positions in the military and the judicial system, and carried on as leading figures in politics and big business.6 For example, Hans Globke, who had been the Nazi’s official commentator on the 1935 Nuremberg Laws stripping Jews of German citizenship,7 subsequently served as a head of the Federal Chancellery and as West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s National Security Adviser from 1953 to 1963.8 During the height of the student movements, Kurt Kiesinger, who had worked in the Nazi Foreign Ministry’s Department of Radio Propaganda, was chancellor of West Germany from 1966 to 1969.9 Furthermore, at the Federal Office of Criminal Investigation (BKA, Bundeskriminalamt), established in 1951 and later instrumental in the fight against terrorism, former Nazis held forty-five of the forty-seven high-level administrative appointments in 1958; of these forty-five former Nazis, thirty-three had been members of the Shield Squadron (SS, Schutzstaffel).10 The Ministry of Federal Intelligence (BND, Bundesnachrichtendienst), founded in 1956, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (AA, Auswärtiges Amt), set up in 1951, have also recently conducted studies and publicly acknowledged having hired former Nazis and SS.11

The postwar society had periodically confronted the Nazi past through trials. From 1945 to 1946, the Nuremburg Trial prosecuted twenty-three high-ranking political and military Nazis,12 and in 1961, the trial of Adolf Eichmann took place in Israel. Yet it was the Auschwitz Trials, which were held from 1963 to 1965 in Frankfurt am Main, that politicized the younger generation that would become the 68ers vis-à-vis the Nazi past.13 For example, Christian Semler—a future leading figure in the Socialist German Students’ Union (SDS, Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund)14—worked his way through the Nuremburg Trial’s files when he was a law student and discovered that a former neighbor, who was a doctor, had participated in experiments conducted at a concentration camp. Likewise Kursbuch—which was cofounded by Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Karl Markus Michel, and which wound up being one of the most influential publications of West Germany’s Extraparliamentary Opposition (APO, Ausserparlamentarische Opposition)—included an article by Martin Walser on the Auschwitz Trials in its first issue published in 1965.15 In a seven-hundred-page introduction to the hearings, which drew on the testimony of “254 witnesses, both survivors and former SS officers from Auschwitz,”16 prosecutors described the three camps and the crimes committed at Auschwitz.17 Over the course of the trial’s two-year duration, hundreds of witnesses, including survivors and former guards, were called to testify. West German media provided wide coverage of the trial and the testimony of the witnesses. Venues that covered the court each day included the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurter Rundschau, Frankfurter Neue Presse, and Die Welt.18 Moreover, a two-volume work including much of the testimony was published shortly after the trial. Yet, as Rebecca Wittmann argues, as a result of limitations in the West German criminal code and how it was interpreted, as well as of media coverage of the trials,19 atrocities committed were depicted as isolated acts of particular sadists, rather than as resting on and implicating widespread support for the Nazi regime.20

While West Germany continued to grapple with the legacy of the fascist era, the period after the Second World War also marked the beginning of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union—and West Germany rested at its front lines. As outlined in the Truman Doctrine (1947), the United States sought to prevent the spread of communism, by following a policy of containment.21 West Germany became a bulwark in this effort.22 Truman’s subsequent Marshall Plan (European Recovery Program) provided funding to Western European nations from 1948 to 1952 chiefly to help postwar economic reconstruction efforts but the aid money was contingent on the implementation of free trade policies.23 It contributed to but was not solely responsible for the economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder) of West Germany in the 1950s, characterized by consistent growth in the gross national product, investments, and imports and exports.24 These factors, in turn, led t...