![]()

1

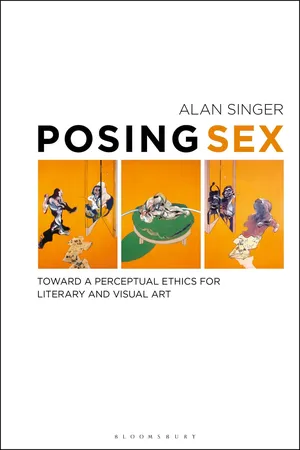

Posing Sex: Prospects for a Perceptual Ethics

Introduction

Sexuality and sexual desire remain tantalizing conundrums for the universalizing human intellect, desirous as it is of comprehending the human condition even in its most unconditional manifestations. The representation of sexuality in the history of art is of course ubiquitous. But our equivocal rapport with this subject matter, whether through attraction or repulsion, too often goes unacknowledged as an opportunity for reflecting, with unusually rigorous candor, upon the bounds of our subjectivity. This speculative failure is nowhere more conspicuous than in our attempts to make aesthetic judgments with respect to representations of sexuality while ignoring our intuitional complicity in the perceptual grounds adduced by all such representations.

Our encounter with images or discursive accounts of sexual activity, especially when they incite a moralistic recoil from the sensorium they animate, stymie the very agency which is presupposed in our attentiveness to them. Roger Scruton has succinctly grasped the horns of the dilemma in his Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation:

Sexual arousal is a response, but not a response to a stimulus that could be fully described merely as the cause of a sensation. It is a response, at least in part, to a thought, where the thought refers to “what is going on” between myself and another. Of course, sexual pleasure is not merely pleasure at being touched; for that could occur when one friend touches another, or a child its parent … It is nevertheless … an intentional pleasure, and if there is difficulty in specifying its object this is largely because of the complexity of the thought upon which it is founded.1

The complexity Scruton invites his reader to engage might be pointed up most sharply by a question. What does it mean to represent the sexual act? The answers are as multifariously confusing as sexual acts are deemed to be perverse by their vaunted polymorphism. Moreover, in answering the question, we encounter myriad contradictions. They play havoc with the commonplace that such a durable representational practice—what I will call the sex image—is a compelling threshold of human self-recognition, at least in the codices of Western cultural identity. For depictions of coitus situate us conflictedly, but on epistemically familiar ground, between the demands of the mind and the body. They embody, so to speak, the burden of reconciling mutually exclusive desires: the pursuit of knowledge and the satisfaction of physical appetites. Not surprisingly then, any inquiry into what it means to represent the sexual act founders upon what I intend to show are the falsely mutual exclusions with which binary thinking so unconscionably intimidates thought.

It is apparent on all of the salient topoi of contemporary debate about the sex image that a burdensome Cartesianism inhibits our ability to think more productively about what it means to represent the sex act and how such representational practices inflect both sexual identity and cultural self-knowledge. We must think specifically of the rubrics of pornography and erotica insofar as they proffer the possibility of erotic art as a legitimate resource of human self-understanding. Or do these rubrics actually invite the perverse possibility that art may not be a meaningful venue of aesthetic experience in the first place? Each of these arenas of debate historically has been dominated by the presupposition that fevered sensation thwarts higher cognitive ends of human activity. For my purposes, however, the significance of how sensation figures in thinking about sexuality is a corollary of our knowledge of aisthesis generally. I maintain that in aisthesis, sensation is a sine qua non of any consequential knowledge of existence in the realm of being human. And so the apparently narrow purview of the sex image will be seen to disguise an unexpectedly expansive horizon of inquiry about the sources and uses of aesthetic experience in general. My own sources for opening the question of what it means to represent the sex act—Greek Stoicism of the second century, the Ethics and the Treatise on the Improvement of Understanding of Baruch Spinoza, and the aesthetic intimations of Gilles Deleuze’s Spinozan inquiries into the Stoic roots of counter-metaphysical self-knowledge—establish a new frame of reference for the sex image. They intimate the inextricability of our dangerous arousal to the sensuous intensities of the body, from the even more passionately desired goal of a humane self-explanatory knowledge that might prove to be convincingly, and thus existentially, self-perpetuating.

Conviction and existence are deliberately paired in this formulation. For I am most invested here in the proposition that every sensation of existent being is felt as a conceptualizing impetus and thereby testifies to the urgency of a conceptual capacity. The attitude that casts the sex image as a pretext for ersatz moralizing persists because sensation and the arousal of the senses have been presumed to be inimical to self-reflection and the autonomy of mind denoted in that capacity. Indeed, sensation is not deemed to be a capacity so much as a natural necessity and hence not a resource of human nature that needs enhancement or is susceptible to deliberate, which is to say deliberative, modifications of the perceiving subject.

I wish to link sensation with a view of human being that inheres in the activity of enhancing its native capacities. This presupposes knowledge of what capacities human being possesses. I am presuming, in what may initially appear to be a counterintuitive fashion, that the homiletic admonition of philosophical humanism, that is, know thyself, is belied by ample evidence that we do not know our capacities in a way that could make our claims to self-knowledge consistent with our physical actions. In other words, the admonitory know thyself presupposes a capacity for self-knowledge that we typically assume is latent, already present in the repertoire of human dispositions. I would suggest that it is instead a pedagogical enterprise, the terms of which are dictated by what we do in our ambition to discern its presence. If the body, by dint of its incompleteness with respect to the world of possible experience, is the inescapable threshold of this understanding, as Spinoza, Hume, Hegel, Lacan, Deleuze, and others have warned us, we stand apart from and at odds with the Cartesian story. But this does not necessarily comport with an all-too-familiar and an all-too-reductive anti-Cartesianism. Descartes urges our conviction that the substantive elements of experience—will, imagination, the senses, and intellect—are all already readily discoverable within ourselves. Despite his basic internalism, Descartes does appreciate the necessity of perceptual experience, if only as what resists the thing that thinks. What is significant in the arguments of his critics, from my point of view, is the possibility that states of mind proliferate in a way that Descartes’ ultimate overcoming of sensation and bodily presence cannot fully appreciate.

Philosophers of perception such as Alva Noë2 now argue that our representations of the world are adequate to our experience of the world. This is deemed to be the case not because there is a determinative causal link between one and the other, but because the states of mind occasioned by the form of the world and the states of mind occasioned by our representational faculties are the same. The succession of states of mind is key to our grasping the world in a manner consistent with my contention that conceptualizing and perceiving are more inextricable from one another than we might otherwise imagine. This is especially the case if we are prone to imagine that we can know who we are when such knowledge is decoupled from what we are doing. My proposal that the sex image could yield access to a complexity of thought commensurate with Scruton’s expectations for the philosophical investigation of sexual desire must, however, take a different trajectory than Scruton’s. My thinking is more in line with Noë’s refutation of what is commonly known as the “sense-datum theory of perception.”3 This is the proposition that perceiving is a way of finding things as they are on the basis of how they appear. Noë counters that things always appear as an index of how we come into contact with them under the motor power of physical activity. Noë’s “enactive” theory of perception, for example, can account for how the “roundness” of a plate derives from the appearance of an ovoid shape as a result of the viewer’s movement in space. Noë stipulates: “One experiences its roundness through the mastery of its sensorimotor profile. One doesn’t infer that the tomato is a three-dimensional whole. One experiences it as a whole insofar as one encounters it by the exercise of an appropriate battery of sensorimotor skills.”4 Usefully, G. Gabrielle Starr has recently concurred with Noë. She provides the additional insight that motor imagery, the sine qua non of the sex image as I am treating it, “integrates and remakes knowledge, and, enacted in the brain and in the mind, it can take powerful hold of the self.”5 Such is the touchstone of personhood in my purview. Motor imagery is self-revisionary precisely in the manner that I will suggest reverse anthropomorphism, a provocation to be animate mentally as well as physically, coheres with human choice-making. By my reckoning choice-making inheres in all kinds of human activity, that is, all that is presupposed in the conceptual schema of motor imagery in the first place. Much more will follow in this direction.

It will suffice to say, at this juncture, that I wish to broaden the horizon of aesthetic experience along the lines traced out, however sketchily here, by Noë and Starr. In doing so, I maintain that the perceptual stimulus given by the artwork and, as I claim, most conspicuously figured in the sex image might enable an ethical discourse that does not succumb to the familiar dichotomous stances we are traditionally inclined to take toward physical and mental activities. I wish to consider the possibility that our thinking about our bodies, especially with respect to the conditions of their arousal to the sensuous demands of the world, bears a family resemblance to human intentionality. In other words, the complexity of thought I am after here goes beyond what Scruton alleges to inhere in sexual pleasure per se. I am more interested in sensation as a touchstone for comprehending the capacities for human activity in general. I am taking the sex image as a point of departure because it is so undeniably a marker for comprehending how human being possesses unique capacities. The integrity of these capacities depends upon a self-conscious self-perpetuation of the nature they unfold through sensory contact with the world. Such is the nature of physical desire, after all. And, of course, my earlier invocation of Spinoza’s conatus is deliberate, with the understanding that conatus might be understood simply as appetite or desire attended to by consciousness of itself.6 This is alternative to thinking of desire as arising from an unconscious wellspring of mentality that is at the mercy of sense stimuli.

Clearly, I am working here on the assumption that the scene of sexuality entails recognition of the urgency of perception, more emphatically than almost any other representational topos.7 This is to say that I am not interested in the scene of sexuality as a genre, a compositional armature, or a thematic register. Likewise, I will not take up non-Western works such as the Kama Sutra which are instructional or bound within religio-symbolic practices. I prefer to take the scene of sexuality as an existential occasion. It seems uncontroversial, particularly within the precincts of Western aesthetic theorizing, to assert that the artwork is always occasional with respect to the perceptual conditions it orchestrates for its audience and according to which that audience is made to feel its own powers of apprehension. For this reason, I will discount the importance of many noisy contemporary debates that I consider to be red herrings, such as the question of whether or not art and erotica are mutually exclusive propositions or compatible modes of representation. Nor will I rehearse the debates about what constitutes pornography vis-à-vis other forms of expression bearing on sexuality. The etymological links that marry the category of pornography (and its baggage of pseudo-moralizing) to the porne of antiquity—that is, the notion that what I am calling the sex image merely solicits arousal—is secondary to the question of who is aroused.

Indeed, one of the commonplace criticisms of pornographic representation is that it depersonalizes the consumer, not to mention the solicitous porne.8 The question of who the depersonalized person is, depersonalization notwithstanding, too often goes begging in this complaint. On the contrary, I am most interested in whom the subject of arousal might become vis-à-vis newfound expressive capacities. This requires our understanding how one knows what capacities one possesses and how such knowledge enhances the prospect that the possessor of those capacities might be self-perpetuating in ways in which enliven our ethical relations with one another. If I can satisfy these conditions of understanding, I will be in a position to allege the collaboration of aesthetic and ethical purposes as a significant substrate of the personhood that I say is augured in the sex image. All of this argumentation will be critical to reckoning with the already time-honored (but just as perennially misunderstood) proposition that the work of art matters to persons because personhood presupposes something like the activity of the artist.

The sex image and enactment: Examples

I now take up two examples. They epitomize the activity of the artist inasmuch as it is a compelling underpinning of the personhood that interests me with respect to the provocations of the sex image. Marquis de Sade and Georges Bataille uncontroversially denote what we are socioculturally meant to pigeonhole as erotica or pornographic literature. But rather than indulge categorical judgments here I wish to assert that the imperatives behind such judgment are aroused by a formal gesture. It is one that both authors make unapologetically: the stylistic refusal to mediate, figurationally, the reader’s encounter with the brute physicality of the sex act. For the moment, I will demur any discussion of the putative moral “scandal” of such a representational gesture. In the long run, I will attempt to dismiss this preoccupation altogether. Instead I wish to pay scrupulous attention to the representational gesture in relation to the experiential contingency it instantiates: specifically what I will refer to as a two-step perceptual protocol that is operative in the texts of these authors on the model of Noëan perception. I will give more detailed attention to this protocol in the next section. It is enough to say now that such a protocol specifically refutes the sense-datum theory of perception: the usual warrant for declaiming the scandalous intent of these authors. The idea that the object of sense experience—in the case of the sex image—is independent of conceptualization, the notion that concepts may be successfully conflated wi...