![]()

1

On the Limits of Narcissism: Alain Delon, Masculinity, and the Delusion of Agency

Darren Waldron

In classical mainstream cinema, the male has been objectified despite himself, as if unaware that he is offered for the erotic pleasures of the audience. However, in the case of Alain Delon, as many commentators have observed, his early image was predicated upon the “narcissistic display of his face and body” (Vincendeau 2000, 174) (Figure 1.1). In the early films in which he starred, such as Plein soleil/Purple Noon (René Clément, 1960) and La Piscine/The Swimming Pool (Jacques Deray, 1969), the narrative flow is briefly suspended to afford a contemplation of his striking, sensual beauty. The actor embraced this pervasive camera, famously boasting that he was an homme idéal (ideal/perfect man) (in Jousse and Toubiana, 1996, 31), although Vincendeau characterizes him as an homme fatal that functions as “both object of the gaze and narrative agent” (2000, 177). And yet, the extent to which Delon can be described as an agent in the broader sense can be questioned. His characters are frequently marked by their inability to gain mastery over their existence, resulting in or caused by their alienation from the world, a lack of power that can be broadened out as a commentary on his star image as a whole.

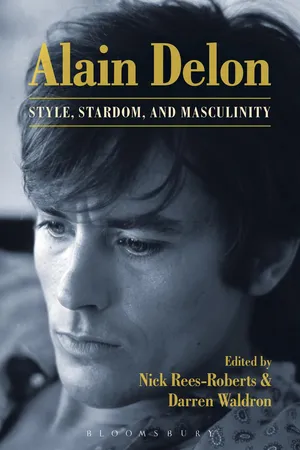

Figure 1.1 Delon in his prime as Tom Ripley in Plein soleil (1960)

This discussion explores the narcissistic mode of representing men and of male stardom with specific reference to Delon’s emblematic gigolo roles as Tom Ripley in Plein soleil and Jean-Paul in La Piscine. It attempts a reading of Delon’s early image through the prism of Simone de Beauvoir’s discussion of narcissism in the “justifications” section of the second volume of Le Deuxième Sexe/The Second Sex (1949). Such an approach carries obvious tensions, given Beauvoir’s focus on the “condition” of woman. Yet, the homme-objet (male object) raises issues with regard to subjectivity not dissimilar from its female counterpart. This chapter probes how, in colluding in his construction as a male object and ideal, Delon grants power in affirming his subjectivity to the objectifying other, that is filmmakers and the audience.

Narcissism and the delusion of agency

The term narcissism, as is popularly known, originates in Greek and Roman mythology. Variations of the original myth exist, with the most popular casting it as a tragic tale of non-consummated self-love.1 Ovid’s version from his third book of Metamorphoses (8AD) frames the myth as a story of revenge between Narcissus and Echo, a mountain nymph doomed to repeating the words of others. After Narcissus spurns Echo, she spends the rest of her existence heartbroken, which Nemesis avenges by having Narcissus fall in love with his reflection in a pool of crystal clear water and then die through grief at not being able to consummate his erotic urges toward himself. Other interpretations, such as that recounted in Robert Graves’s “complete and definitive” edition of the Greek myths, have Narcissus commit suicide; after sending a sword to ward off Ameinius, one of his (male) suitors, Artemis punishes Narcissus for his vanity by making him fall in love with his image and stab himself. As Graves asks rhetorically, “how could he endure both to possess and yet not to possess?” ([2011] 1955, 287–88).

In more modern times, narcissism has been attached to certain “personality” or “character” disorders, in which outer love of the self is often seen as a marker of inner low self-esteem. According to Freud, narcissism constitutes a “normal” phase of child development and is concerned with self-preservation. Primary narcissism refers to the infant’s love of itself (ego libido), in which, the child, in effect, represents for himself his own ideal (ideal ego). When the adult takes another person as the object of their libidinal energies, primary narcissism is diluted, but secondary forms of narcissism can still surface, partly as a consequence of repression (1998, 151). As the growing child becomes aware of the criticisms of others and those that come from within “him,” “he” seeks to “recover” the “narcissistic perfection of his childhood” in the “new form of an ego ideal” (1998, 151). Narcissism constitutes an erotic investment in the self, unlike sublimation, which “consists in the instinct’s directing itself toward an aim other than, and remote from, that of sexual satisfaction” (1998, 152).

Freud’s account of narcissism (and those of the many scholars that build on it) can offer fruitful resources for interpreting Delon’s childhood and youth as they are reported in the press and biographies. In his self-proclaimed “unauthorized” study of the star’s life, Bernard Violet reveals how the infant Delon was first indulged by his mother and then, seemingly, rejected (2000, 13; 17). Following her second marriage, Édith Boulogne (Mounette) gave birth to a daughter, baptized with the first names of both parents to symbolize the reciprocity of their relationship (Paule-Édith). Delon, having been born to Mounette’s previous husband (Fabien Delon), still bore the name of his father. Delon misbehaved and was dispatched to foster parents and sent to boarding school, which he is reported as having experienced as a rejection (Violet 2000, 19). Carrying a sense of excess to the requirements of his parents in their new relationships, Delon continued to rebel and was apparently expelled from numerous religious educational institutions (Violet 2000, 19). His unruly behavior could thus be interpreted as the product of someone forced to elevate themselves as compensation for their sensed alienation from the external world. It was allegedly during this period that Delon became aware of his potential to disarm through his looks (Violet 2000, 20). Projections of omnipotence derived from a narcissistic valorization of his erotic appeal would feature among the most prominent markers of Delon’s star persona. Yet, such assertions of apparent power can constitute affectation and this is made clear in the frequent obvious signs of vulnerability and self-doubt that traverse Delon’s career and image.

Striking resonances emerge between Delon’s reported personal life and public image, and what Wilhelm Reich labeled as the “phallic-narcissistic character” (1933, 217–25). For Reich, the phallic narcissist is often raised by a strict mother and “his” desire for vengeance is then played out in “his” sadistic and selfish attitudes in “his” relationships with women. “He” tends to be “self-assured, sometimes arrogant, elastic, energetic, often impressive,” while “his” physique is “predominantly an athletic type” but often accompanied by “feminine, girlish features” (1933, 217). “His” narcissistic sensitivity leads to “sudden vacillations from moods of manly self-confidence to moods of deep depression” (1933, 221). Much of “his” behavior is concerned with defending against “anal and passive tendencies” and can thus be triggered by repressed homosexual urges (1933, 221). Some of this behavior is attributed to Delon, as evidenced in the recollections of former peer and friend Jean-Claude Brialy, who remembers his violent and/or indifferent behavior toward his female partners, including Brigitte Auber and Romy Schneider, as well as his domineering attitude toward Brialy himself (2000, 131–32; 143–46).

The idea that mastery of the self can be achieved through narcissistic forms of self-affirmation of the kind that Delon is said to have engaged in is delusory—or rather self-delusory. It is here that we might fruitfully turn away from psychoanalysis and to existentialism in order to elucidate better how this delusion/self-delusion plays out in material terms. Narcissism can be understood as a form of bad faith in the existentialist sense in that it allows us to avert our attentions away from the not-yet-known of our future lives and preoccupy ourselves within the already-known of our present (and past). As such, it is a means of evading the freedom to self-determine that existentialists believe characterizes human existence. As Jean-Paul Sartre famously argues in L’Être et le néant (1943), as human beings endowed with consciousness, we can transcend our current situations and act for ourselves. Although we may feel inhibited by our past experiences and current circumstances, to use these as justifications for not choosing our freedom is to engage in bad faith. While perhaps not narcissistic in its purest sense, the behavior of the café waiter famously described by Sartre illustrates this cogently. For Sartre, as the waiter invests meticulous attention in executing his duties perfectly, he plays at being a waiter. Although he might believe that he affirms mastery through his behavior, ultimately, his actions serve to limit his existence to a being-in-itself as a waiter (1943, 94).

Owing some philosophical debt to Sartrean existentialism, as well as to phenomenology and Marxism, Simone de Beauvoir pursues these ideas further in her examination of narcissism and the “condition” of “woman.” Patriarchy, according to Beauvoir, works to bind woman to certain roles and situations, mainly marriage and motherhood, thereby imprisoning her within a realm of immanence and denying her transcendence. Somewhat controversially, Beauvoir reveals how women, as well as men, perpetuate this unequal distribution of power through an internalization of patriarchy’s values via gendered forms of bad faith, of which narcissism is a prime example (1949, 519–84; see also Boulé and Tidd 2012, 4–5). As Linnel Secomb notes, transcendence assumes a specific meaning for Beauvoir, it “involves reaching beyond the constraints of immanence, beyond entrapment within biology, social convention and repetitive domesticity, embracing freedom through active involvement in the public world” (2012, 87). The female narcissist embarks upon a strategy of self-deception wherein she overinvests in her beauty and attractiveness, and seeks to convince herself that she achieves agency and power by virtue of her physical appeal. Such an endeavor is self-delusory because it involves attempting to affirm a free, transcendent subjectivity through the apprehension of the self as both subject and object, which for Beauvoir is impossible: “it is not possible to be for self positively Other and grasp oneself as object in the light of consciousness” ([1949, 520] 2009, 684).

That Beauvoir was writing about the situation of woman in no way makes her points meaningless when discussing the situation of certain men. As a film star, Delon derives acclaim from putting himself, intentionally, in the public domain.2 Moreover, given that the substance of that stardom derives, in his early performances in particular, from his status as erotic male on display, he can be described, like the female narcissist, as a prisoner of that existence. Although not in the section that specifically addresses narcissism, Beauvoir uses the example of the female Hollywood star to illustrate the limitations of celebrity, reminding us that, while “she” thinks “she” enjoys some form of autonomy, “she” is nonetheless always someone else’s object (1949, 396; see also Boulé and Tidd 2012, 5–6). According to Beauvoir, that someone else is the producer, but, as we know, the star is also beholden to the audience’s wishes, expectations, desires, and fantasies (Dyer 1998 [1979], 19–22). Many stars are trapped within an externally defined identity, incarcerated within a realm of contingency determined by others. Like Sartre’s waiter and Beauvoir’s female narcissist, though, they are complicit in this entrapment; it is not that they are unable to escape their situation, but through their actions of seeking to reaffirm and revive their appeal, they perpetuate their dependence, arguably despite knowing the stifling impact of such a status for self-determination. The implications of this for Delon’s image and its manifestations within his performances in Plein soleil and La Piscine will be examined in detail in the next section.

Plus ça change …: Delon’s gigolo persona and its implications

As commentators have noted, Delon’s early persona was closely associated with the figure of the international playboy and/or gigolo (Vincendeau 2000, 175; Bruzzi and Church Gibson 2008, 165), and this is perceived as a convergence of his roles with his real life as reported in the press. Though semantically distinct—the playboy might be perceived as more independent than the gigolo, who lives from his erotic relationships with well-heeled and usually older women—both sustain their existence, attain a sense of self and attempt to affirm agency through an investment in their physical allure. Nowhere is this embodiment of the playboy/gigolo figure more obvious than in Delon’s two iconic roles as Tom Ripley and Jean-Paul. In fact, La Piscine bears a complementary relation to Plein soleil; Jean-Claude Carrière recalls that Plein soleil was a constant presence in the minds of the film crew during the shooting of La Piscine (DVD extras) and such congruence is evident in the casting of Delon and Ronet as rivals, the former as killer, the latter as his victim, murder plot narrative and southern European settings.

The adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley (Patricia Highsmith, 1955), Plein soleil centers on Tom Ripley (Delon), a man of limited finances, who has been dispatched to Italy to bring Philippe Greenleaf (Ronet) back to America by Greenleaf’s father, for $5,000. Tom envies Philippe’s playboy lifestyle, while Philippe exploits Tom’s dependency; during a yacht trip, he abandons Tom in a dinghy in the blazing sun and casts his girlfriend Marge’s (Marie Laforêt) manuscript on Italian Renaissance painter Fra Angelico into the sea. Tom attempts to avenge and affirm mastery over his friend by stabbing Philippe, dumping his body in the sea, and assuming his identity. However, his endeavors are frustrated by the suspicions of Philippe’s friend, Freddie Miles (Billy Kearns), whom he also murders, and chief inspector Riccordi (Erno Crisa). Realizing that his plan has failed, Tom fakes Philippe’s suicide by forging a letter as Philippe in which he bequeaths his estate to Marge. Tom seduces Marge, but even the compromise of attaining wealth through romance is, it seems, denied him. As he smugly sips his drink while basking semi-naked in the sun (Figure 1.2), the film crosscuts to shots of the yacht being winched from the sea, with Philippe’s corpse seemingly attached to the propeller and, later, of Riccordi waiting to seize and arrest him. Tom’s envy of Philippe is mirrored and extended in Jean-Paul’s jealousy over Harry (Ronet) in La Piscine. Jean-Paul is a writer in a relationship with his wealthy girlfriend Marianne (Romy Schneider), with whom he is staying at her summerhouse in the south of France.3 Harry, Marianne’s playboy ex-lover, visits for a few days, accompanied by his daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin). After seducing Penelope, Jean-Paul drowns a drunken Harry in the pool, which he then portrays as an accident. When inspector Lévêque (Paul Crauchet) suspects that he is Harry’s killer, Jean-Paul confesses to Marianne, who later denies his involvement to Lévêque.

Figure 1.2 Tom Ripley basking in the sun at the end of Plein soleil (1960)

Beyond actor, plot and location, the sensual display of Delon’s face and body at a time when men were not commonly represented as erotic objects closely binds both films. As Bruzzi and Church-Gibson remark “Delon was one of the first male heroes to be stripped and fetishized on screen” (2008, 165), an image that the actor had partially honed for French audiences in his first film appearances. Where the crystal clear waters of a Greek spring reflected Narcissus’s beauty back to him, the deep azure of the Mediterranean Sea that laps against the shores of southern Italy in Plein soleil and the shimmering, translucent waters of a swimming pool in the south of France in La Piscine frame and illuminate Delon’s delicate facial features and toned and tanned body.4

The first time the audience sees Delon’s naked torso in Plein soleil comes during the yacht excursion with Philippe and Marge. When Philippe asks Tom to steer the vessel so that he and Marge can make out in the galley, Tom swiftly rips off his shirt to reveal his chiseled chest and stomach. The camera films him in medium long shot, the impression of voyeurism enhanced by its position behind the ladder leading down from the deck. For an instant, Tom stands motionless, as if wittingly exhibiting his body for the enjoyment of others. Marge and Philippe are, very momentarily, silent, their apparent surprise inscribing within the narrative the possible astonishment of the spectator as s/he witnesses this unexplained exhibition of naked male corporeality. Tom’s strip to his waist foreshadows what is arguably the film’s most famous sequence, in which Delon is sat, upper body exposed, behind the yacht’s large wheel, a version of which was used for the film’s poster.

The intertextual linking of La Piscine to Plein soleil through the display of Delon’s physique is instantly evident in the later film’s opening sequence. A tracking shot slowly glides over the water’s surface to Delon in deep repose, basking in the bright sun, dressed only in his tight swimming trunks, before Marianne awakens him from his semi-slumber. Recollections of Tom/Delon sunbathing in the final shots of Plein soleil are immediately triggered, but the sexual...