![]()

1

BURTON DOES 2-D: FROM ANIMATION TO MACHINIMA

I think best when I’m drawing.

—Tim Burton1

Given Burton’s visual fair, it is perhaps no surprise that he began his professional life in animation, a medium in which anything is possible, where constraints of imagination, time and place have little meaning. In many ways Burton’s movies can be seen as animated exercises shot as live-action, since they deal with characters and situations that exist outside the realms of reality. [Says Burton,] “People ask me when I’m going to make a film with real people. What’s real?”2

Mark Salisbury’s comments on Tim Burton articulate the basic concept on which this book is organized. However, the fact that Burton began his professional life as an animator can be misleading, as he was producing, directing, and starring in live-action films, shot in Super 8, which he made with a group of friends, from his teens into his early twenties. Unfortunately, these films are now lost, though I did find a cryptic reference on the Internet to The Island of Dr. Agor (1971), made when Tim Burton was thirteen.3

Burton loved to draw as a teenager. At fourteen, he even won a poster contest for a litter campaign. (The logo was “Crush litter,” and the posters were pasted on the sides of town garbage trucks for a year.) Burton also made pocket money by painting his neighbors’ windows for Christmas and Halloween decorating. He credits the encouragement of one of his teachers in high school for the fact that he got a scholarship to the California Institute of the Arts when he was eighteen.4

The institute is located in Valencia, California, twenty-two miles northeast of Burbank, Burton’s childhood home. Walt and Roy Disney established the school in 1961. In 1975 the Disney estate gave Cal Arts a $14 million endowment to train animators for their TV studio. In 1976 Burton started as a scholarship student in the film department. Burton notes that “[a]t Cal Arts we would make Super 8 movies: we made a Mexican monster movie and a surf movie, just for fun. But animation—I thought that might be a way to make a living.”5

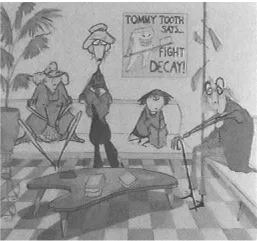

Disney had a practice of hiring (Burton described it as a “draft”6) student animators right out of the Cal Arts program. Usually the studio executives looked at seniors, but they often hired lowerclassmen as well. This made the atmosphere among the animation students very competitive, as everyone wanted Disney to pick them; at the time, animators did not have many other places to go for employment. Burton loved to draw, but he was feeling financial pressure because in his third year his scholarship was taken away, the result of some bureaucratic mix-up. Burton was in the financial aid office arguing for its reinstatement every day, even as he prepared his final project for the year, a pencil test animation entitled Stalk of the Celery Monster, in which a Frankenstein type of doctor, aided by a huge, veiled mountain of an assistant, seems to be conducting evil experiments on a female patient. Finally, the mad scientist is revealed to be an ordinary dentist, as he cackles, “Next, please . . .” to the other patients in the waiting room.

A clip from Stalk of the Celery Monster can be seen in the A&E Biography episode “Tim Burton: Trick or Treat.” Even this brief segment reveals some stylistic details that would become Burton trademarks: a lead character whose actions and intent are misunderstood; an unwilling (and often, as in this case, almost deformed) assistant; the mad-scientist theme; and lovely women either being restrained by a madman or looking directly out at us, their already overly large eyes made larger by their expression of terror. According to Rick Heinrichs,7 Stalk of the Celery Monster got the attention of the Disney headhunters because, unlike most of the other students who used their films to perfect various animation techniques, Burton used his to tell a story and to create a complex set of relationships between a group of characters.8 Nobody was more surprised than Burton when he was selected in 1979:

The monstrous scientist from Stalk of the Celery Monster about to torture a bound female.

As the years went on, the competition, the films, would get more elaborate, there was sound, music, even though they were basically pencil tests. The last one I did was called Stalk of the Celery Monster. It was stupid, but I got picked. It was a lean year, and I was lucky, actually, because they really wanted people.9

By hiring him, Disney gave Burton a source of income and an identity—the identity of an animator, which he retains to this day. But the price was very high. His first assignment was working on The Fox and the Hound (Art Stevens, 1981), under the supervision of Glen Keane. Burton had a lot of respect for Keane: “He was nice, he was good to me, he’s a really strong animator and he helped.”10 But he hated the job of drawing “all those four-legged Disney foxes, I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t even fake the Disney style. Mine looked like road kills. So luckily I got a lot of far-away shots to do.”11 As a result, Burton’s first year at Disney was miserable, and he gradually sunk into a depression, sleeping fourteen hours a day (he learned how to sleep at his desk with his pencil in his hand), or hiding in his closet or under his desk, or walking down the hallways after his wisdom teeth had been removed, letting the blood stream out of his mouth. However, when he did work, he worked fast, and apparently enough to make sure that he didn’t get fired.

The electrical zapping lines of torture from Stalk of the Celery Monster will be seen again as life-giving in Frankenweenie.

The scientist in Stalk of the Celery Monster is revealed to be a mere dentist, and the whole horror story a projection of our dental fears.

Part of the problem is that the Disney Company as a whole was in the middle of an identity crisis. The animation department had shrunk from a high of 650 artists to 200. In 1979, the year Burton started at Disney, Disney’s Chief Animator Don Bluth left, taking with him seven other animators and four assistants, to produce feature-length animated films for Steven Spielberg. The success of Don Bluth’s An American Tail gave Disney its first taste of real competition in the animation field.12 Burton was quite sensitive to the sense of disorientation and confusion in the atmosphere, with movies like Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo contrasted with films like Tron (for which Burton did some in-between work). Disney’s internal divide was characterized by the contrast between the remnants of the old-style animators, “just a couple of zany gag men in a room,”13 as Burton put it, and the new people struggling to take Disney into the digital era.

Burton’s situation improved when he was given the job of conceptual artist on the film The Black Cauldron, a movie a decade in the making. Cauldron was unique for various reasons: it was the only Disney film to get a PG rating, it had no songs, and it had a rather dark story line. More important, for Michael Eisner,14 at least, it had some of Disney’s first use of computer-generated images in several scenes. The use of computer animation was quite effective, especially in the darker scenes of combat toward the end of the film; one reviewer noted that the digital artwork “gives some of the scenes a surprisingly effective three-dimensional appearance (one tracking shot up the side of a dark castle with lightning flashing is particularly impressive).”15 Eisner credited the digital innovation at Disney to Glen Keane and John Lasseter (the latter would go on to produce Toy Story, the first fully computer-animated movie),16 though, like Burton’s, none of Keane’s animation made it into the film.

Cauldron was a failure at the box office, and Disney took it off the shelf for thirteen years. The reasons have more to do with the story than with the animation (although the figure of Taran seems to be a bland copy of Arthur in The Sword in the Stone). Though based on the first two books of Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain series, the film seems to be aiming for the Star Wars audience; Taran’s sword even looks like a light saber. Many critics, including Roger Ebert,17 also noted the resemblance of the climax to that of Raiders of the Lost Ark, though the same critics said the visual treatment rose above this copying.

The film’s real problems are with the story. Taran starts out as an assistant pig keeper, and in the end he returns the magic sword he has used in several battles in order to resume being an assistant pig keeper (instead of returning the magic sword because he has grown into his warrior role sufficiently to no longer need it). Darker fantasy films are designed to help children face the rigors of adult life, but this one gives a conflicting message, about Taran’s aspiring to be a warrior, actually saving his world, along with the princess, a couple of friends, and the prophetic pig from a fate worse than death, but then walking away from his leadership role. In addition to this major flaw, the film is marred by smaller plot holes: the wizard that Taran works for sends him out unprepared and does nothing to help him (all of his help comes from strangers), and the pig’s prophetic powers are vastly underused, considering the situation in which the characters find themselves. Most of the logic of Lloyd Alexander’s world (a world very similar to that of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, since both are based on the same set of British myths) is completely lost in the Cauldron screenplay.

Burton resented the fact that none of his conceptual drawings were used in the final film: “I basically exhausted all of my creative ideas for about ten years during that period. And when none of it was used ... I felt like a trapped princess.”18 However, the experience was probably not a complete waste. It seems that Burton was aware of the film’s story flaws and learned something from Cauldron’s failure, as his Sleepy Hollow has a very similar plot, in a very similar world, and ignores key elements of its source material in a very similar way, but without the problems we see in Cauldron. (For a more in-depth comparison between the two films, see Chapter 2.)

Burton was not the only one who was chafing at Disney’s schizophrenic atmosphere of dictatorialness and confusion. Others working at the company felt the same way, and they banded together with Burton on weekends and whenever they had spare time to make two live-action films, Doctor of Doom (1980) and Luau (1982). Neither film is available for public viewing, although clips from each can be seen on the A&E Biography video Tim Burton: Trick or Treat. Doom was filmed in black and white on video, with a deliberately bad overdubbing in order to make something that looked like a foreign import from the sixties, with Burton playing Dr. Doom. Luau is an energetic homage to beach-blanket movies and other B movies, complete with song-and-dance numbers, with Burton starring as the disembodied head of “The Most Powerful Being in the Universe.”19 Among the Disney colleagues who worked on these films with Burton was John Musker, who, along with Glen Keane, Burton’s original mentor at Disney, would go on to help usher Disney into a new era, an era characterized by the extensive use of digital technology, with films like The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast.

Though none of Burton’s conceptual artwork for Cauldron was used in the final film, it did get the attention of Disney executive Julie Hickson, who enabled Burton to produce the stop-motion short Vincent, in 1982 (I discuss this film in depth in Chapter 3). After Vincent, Burton made another short at Disney, Frankenweenie (see Chapter 2), which led directly to his being tapped as director for his first commercial live-action feature film, Pee-wee’s Great Adventure (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of Pee-wee’s narration and Chapter 3 for a discussion of its special effects).

For all intents and purposes, Burton left 2-D animation...